Essay (back

to top)

Summary:

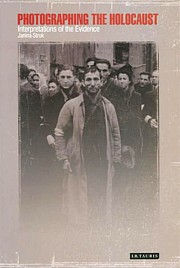

In her book Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence, Janina Struk examines the use of photography during and after the Holocaust, looking specifically at the ways in which the photos have been used in understanding the events. She looks at how the Nazis used photography as propaganda, to show how Jews were different from Aryans, as well as to portray an extremely idealized version of the camps. She then traces the use of photography to show the horrors of the camps and the Nazi regime, to the photographs taken during the liberation. She then asks how the photographs have been used and interpreted. She ends with the question of the meaning of the photographs and what their importance is today.

The first half of the book looks at how photography was used immediately before, during and immediately after the Holocaust. The Nazis used photography as a propaganda tool; they published posters and pamphlets on how to identify Jews and on what separated them from Aryan Germans. They took pictures of the concentration camps, which portrayed the workers as heroic figures who worked with the guards to create a better Germany. Photography was also used to portray Nazi party figures as powerful leaders; Hitler’s personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann had enormous control over what images would be published. It also examines the “war” of propaganda—German images were flooding British and American media, and the British were hard-pressed to create images that would show the horrors of the Nazi regime. The need for evidence led to a huge underground smuggling ring of photography, as the Nazis began to ban the use of photography by people who not been aprroved by the government. The same image could be interpreted differently, depending on who was using it, and the propaganda war led to doubts as to the factuality of certain photographs.

Struk also examines the photography of the ghettos, noting that often official photographers as well as bystanders produced many of the now famous images shown today. The photographs of the Jews in the ghettos range from voyeuristic shots to almost portraits, with the victims seen looking directly at the camera, sometimes even managing to smile. The frequency of the photographers coming to the camps increased as the number of deaths increased, and instead of the horror one would expect from seeing the camps, many visitors viewed them with a sort of fascination. A few Jews, however, managed to capture images of the atrocities in the ghettos, as an attempt to show them to outsiders in hopes of aid. Photographs taken in the camps could sometimes be smuggled out for use in underground resistance movements.

The images of the liberation of the camps are also discussed. American and British soldiers were horrified by what they saw, and one photographer notes that the use of the camera was a relief, since it acted as a shield between her and the events (124). The images were shown to audiences at home, but were also shown to German citizens, so that they could see the actions of the Third Reich. The images taken of the camps were used in a new wave of anti-Nazi propaganda, meant to show society of the suffering endured by victims of the Nazi regime.

The next section of the book examines how photography has been used since the war. In the years immediately following, the Nazi atrocities were frequently published and exhibited, but as the US and the Soviet Union entered the Cold War, the focus was taken off of the Nazis. The persecution of the Jews was replaced by the national memory perceiving the persecution of countries as a whole. Showing the images became controversial, and Jews faced conflicting feelings of whether to remember the past or to try to move past it. As the Cold War died down, it “had a decided influence on the way the new Holocaust memory was contructed” (172), as documentaries, exhibits, and even Holocaust tourism became popular. 1993’s “Schindler’s List” was an immensely successful film, and since then many other films have been made about the horrors of the Holocaust.

Struk ends the book with the meaning behind the photos. The photos have been displayed differently in different places, but many museums now try to move past atrocity photos and also show photos of families or life before the Holocaust. The photos now have many meanings, as historical sources, as educational tools, as emotional images, as historical memory. Struk questions the commercial use of the photographs, reminding people that the images are of people suffering, marching to their deaths, living in misery, and that this needs to be respected.

Analysis:

Janina Struk examines the use of photography before, during and after the Holocaust. She does not just examine the photos; what makes Struk’s book unique is that she asks questions that have been largely ignored—such as who took the photos, why they took them, what exactly was going on at the time the picture was taken, and how the pictures have been used. The book presents a fascinating behind-the-scenes examination of the photographs, and asks what their present meaning is. Struk uses historical documents, interviews and the photographs themselves to write her book. By examining not only the photographs, but also various uses and interpretations of them, the book provides a much better understanding of the Holocaust and the events that defined it. Struk demonstrates that the interpretation of Holocaust photography has greatly affected how people then and now have understood the events, and how this has changed its meaning throughout the years.

Photography during the Holocaust was used primarily as a political tool and for propaganda purposes. “The belief that a photograph alone could reflect the true character of an individual had become pivotal to an understanding of photography,” (17) and so as part of the pseudoscience of physiognomy, Nazis took and published photographs of Jews so that German citizens could see the differences between Jews and Aryans. The ability to mass-produce photos led to their widespread political use, changing them from an art form to a propaganda tool. Images of work camps were portrayed as a group effort between prisoners and guards to make a better Germany. Images were also used by the Allies to show the atrocities of the Nazis to garner support for their forces during the war.

The use of photography as propaganda is not surprising. The Nazis were masters of propaganda, and so the general opinion of photographs as factual evidence was a useful tool in influencing the minds of the masses. Struk quotes a 1926 article that said that the “’vivid suggestiveness of photographs’ could be ‘more convincing than any text . . . The majority of readers would regard them as an authentic depiction of reality’” (19). Photographs of concentration camps showed them as “places of tranquility and reform” (20), when today it is known that they were the exact opposite. Jews were discredited, shown as threats, and women were portrayed in humiliating and sexual imagery. These types of images served to dehumanize the Jews, giving the German public real images with distorted meanings. While photos may never lie (or at least in the past), how they were shown greatly affected their meaning.

Another use of photography by the Nazis that Struk mentions is as a weapon, or a threat. People who shopped at boycotted Jewish stores were dissuaded under the threat of having their photo taken (22). This too demonstrates the belief of photos as fact; people had no idea how their images would be used, but knowing that there existed no way to refute such hard evidence, would obey the boycott under the fear of being photographed.

Struk’s first examination demonstrates how the Nazis placed meaning on the photos. By capturing certain images and placing them with carefully constructed text, photography became an important propaganda weapon. In this case, the actual photographs were seen as unquestionable fact, and so meaning was derived from the accompanying text.

The Nazis were not the only ones using photography as propaganda—as Struk points out, the Allies were using images to show the atrocities of Nazi Germany and to garner anti-German sentiment. This resulted in the “war of photographs” between Germans and Allied forces. This demonstrates the importance of interpretation when understanding a photograph—Struk mentions that often the same image could be used for various purposes and interpreted differently. The example she mentions (on page 38) is of an image of two Orthodox Jews digging earth, a hand holding a gun on one side and a civilian holding a pick on the other. This image is shown as an example of the bravery of the citizens of Warsaw, as evidence of Nazi supremacy, or as evidence of Nazi persecution of the Jews (38). This one particular section furthers Struk’s argument of the importance of interpretation. How one image can receive such varying meanings demonstrates that photos may depict events that are true, but what is actually happening and why is subjective. Like the use of personal narratives in understanding history must be taken skeptically, so too must photographs.

The part of the book that raises some of the most difficult questions deals with the photographs taken of the camps and ghettos during the Holocaust. In this section, the questions of who was taking the photos and why they did it become important. Official photographers as well as soldiers captured the deplorable conditions of the ghettos and the camps, not out of a desire to show the atrocities and find help, but rather out of a kind fascination of the events. They were not concerned with how horrible the conditions were or the immorality of the events; instead, they saw the ghettos as the “natural habitat of the Jews” (76). This is almost more surprising than the knowledge of the acceptance of soldiers and other military personnel of the Holocaust. It is more difficult to believe that the photographers could be just as unaffected by the horrors as many of the Nazi soldiers. In these cases, photography of the Holocaust was an almost voyeuristic and a tourist-like action; these photographers appear to see taking the photos not as necessary documentation, but rather as an attempt to capture an interesting or memorable event. Even more amazing are the images where prisoners look, even smile, at the camera. What is going through their minds as photos of their suffering are taken? Unfortunately, these are questions that no amount of examination will be able to answer.

Photographers captured some of the most disturbing images of the Holocaust; images of those who committed suicide, of mass graves, and of the experiments of Mengele. These photographs reveal much of Nazi ideology and their belief that they were the superior race. The sheer fact that these images were taken stretches the mind, and make them that much more emotional. It is difficult enough to look at the images, and they serve as a heavy reminder of the capacities of human cruelty. Ironically, these images, most taken with a blind eye, have become some of the most important images in studying the Holocaust and life in the camps and ghettos.

The images taken by the Allies who liberated the camps, however, were taken with the realization of the atrocities of the Third Reich. These photographs were strongly encouraged, to show people back home the horrors of the camps. These photographs were also, Struk notes, subject to more professional or artistic interpretation, based on the American documentary tradition. These photographs were highly publicized, their emotional factors taken advantage of for shock value. The use of the liberation photos was the first instance of the commercialization of the Holocaust. Struk write that the “most consistent message in all the shock-horror reporting was the allied victory and the superiority of Western democracy” (137). The Soviet liberation of eastern camps was mostly ignored, and so people in the West knew only of the liberation of the camps in Germany. During the Cold War, the events of the Holocaust would be forgotten, as the west focused on a new enemy.

As the years continued, each country had its own interpretation of the war and the Holocaust. The photographs were used during the Nuremberg trials and shown to the public in the years immediately following the war, but were placed in archives and ignored for almost fifty years. The memory of the murders of millions of Jews was replaced by national memory, each country remembering only the death of its own, not placing any specific emphasis on the antisemitism that led to the Final Solution. As the photographs were placed in the background of historical memory, so too were the events of the Holocaust.

The revival of interest in the Holocaust came with what Struk describes as the “commercialization” of the Holocaust. In this section, Struk examines the questionable act of using Holocaust photography in exhibits, books, memorials, etc, and the ways in which the Holocaust has been portrayed in film and the media. She notes the similarities between Nazi propaganda photos of the camps and the image of “healthy-looking prisoners, dressed in clean, neat camp uniforms, unconvincingly pulling carts laden with stones through lush green grass” from the 1978 series “Holocaust” (174). Like so many other events in history, this image presents an idealized version of the Holocaust—actual images could be used to shock the conscience, but portraying it in film would be too much. This along with the series “Shoah,” and movies like “Schindler’s List” and “The Pianist,” Struk notes, make the Holocaust subject to being also portrayed artistically, for aesthetic merit (though she praises the “matter of fact” representation in “The Pianist”). This represents another interpretation of the Holocaust: the need to portray it in a creative medium, attaching fiction and art to add a different understanding of the events. Though Struk is highly critical of this type of portrayal, art is one of the most accessible mediums for people to understand their history and society. She criticizes the black and white portrayal of good versus evil and the carefully planned emotional elements of “Schindler’s List,” but people need stories to feel closer to the events. This film (and others) present the Holocaust in a way that helps to place a barrier between viewer and event, making it more accessible, much like in the way Maus does with its use of animals.

Struk also examines the popularity of Holocaust exhibitions and Holocaust “tourism.” These have changed the Holocaust to a uniquely Jewish tragedy, and she notes the macabre ways in which people observe the artifacts and images of the Holocaust, as well as the tourists who go to the camps to see for themselves. In this case, the Holocaust has become also a business, where ironically, tourists flocked to see the locations of events in “Schindler’s List,” not necessarily where actual events had occurred. She argues that there is something morally questionable about taking photographs in front of the gates of Auschwitz, or by constant exhibits of the victims’ moments before they were sent to the gas chambers. “Didn’t they suffer enough already,” Struk asks, not to have their last moments displayed to the public? (216)

On one hand, Struk is correct—there is something morally wrong with glass displays of suffering people being presented to the public, but she underestimates people. She believes that the images have done nothing to stop genocide, which is only partially true, but they show ordinary people the capacity for human cruelty, and the horrors of totalitarian and racist regimes. People need to understand the Holocaust, and just as Struk has chosen to publish a book with her interpretation of the events (or rather, her examination on the interpretation of the events), these types of images, artifacts and displays are necessary to preserve the memory of the Holocaust. In order to better understand the Holocaust, these images need to be shown and analyzed, to be interpreted and discussed. People need to see to believe. The Holocaust was a dark period in human history, one that society is still struggling to understand. The only danger is that by the constant showing of these images, they become commonplace, so the events do not seem as grim or horrifying; however, putting them away in archives will only make them forgotten.

|