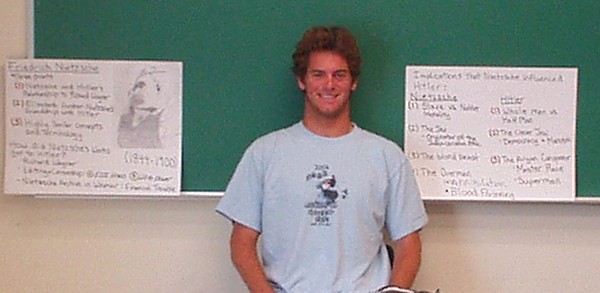

| Friedrich Nietzsche's Influence on Hitler's Mein Kampf by

Michael Kalish student research

paper for |

| Friedrich Nietzsche's Influence on Hitler's Mein Kampf by

Michael Kalish student research

paper for |

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), a fervent philosopher who was anti-democracy, anti-Christianity, anti-Judaism, anti-socialist and self-acclaimed Anti-Christ, expressed his belief in a master race and the coming of a superman in many of his works. In his unique aphoristic style, Nietzsche wrote in The Genealogy of Morals (III 14): The sick are the great danger of man, not the evil, not the 'beasts of prey.' They who are from the outset botched, oppressed, broken those are they, the weakest are they, who most undermine the life beneath the feet of man, who instill the most dangerous venom and skepticism into our trust in life, in man, in ourselves…Here teem the worms of revenge and vindictiveness; here the air reeks of things secret and unmentionable; here is ever spun the net of the most malignant conspiracy – the conspiracy of the sufferers against the sound and the victorious; here is the sight of the victorious hated. Context is a critical factor to understanding Nietzsche's philosophy.

Nietzsche's reference to the sick, their vengeful attitude and conspiracy,

and in related writing, the Jews, parallels the concepts and terminology

used in Hitler's Mein Kampf. However, I do not propose that the

anti-Semitic interpretation of Nietzsche's work began with Hitler. What

Nietzsche-biographer Walter Kaufmann calls the "legend of Nietzsche" (Kaufmann,

1) was constructed mostly by Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche,

through two interventions: by censoring and editing Nietzsche's work to

further her own anti-Semitic interest and to reconcile Nietzsche's work

with Richard Wagner's. Second, in order to finance the Nietzsche archive

Elisabeth exploited Nietzsche's prophetic and radical philosophy to appeal

to her preferred political party. After Nietzsche's insanity in 1889,

the rising tide of anti-Semitism in Germany soon drowned the Weimar Nietzsche

Archive in a sea of swastikas. Can Nietzsche's theories be considered

a foundation for Hitler's Mein Kampf? Hitler's explicit condemnations

of the slave race, his ravings about the Aryan elite, and his proposed

Darwinist resolution, as well as Hitler's relationship to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche

and Richard Wagner signal a definite connection to Nietzsche's work. |

Nietzsche's philosophy did not reach the Nazis untainted by tendentious interpretation. Elisabeth had forced her mother to transfer the property rights and guardianship of the incapacitated Nietzsche in 1895 (Macintyre, 155). Elisabeth became her brother's "chief apostle" with exclusive rights to his work (Kaufmann, 5). The impact of this transfer of rights was assessed in Kaufmann's 1974 interpretation of Nietzsche's work. Kaufmann attributed the roots of what he calls the "the legend of Nietzsche" to Elisabeth, who laid the groundwork for Nietzsche to be interpreted in a literal, Darwinist sense (Kaufmann, 8). Through censorship and editing, Nietzsche's philosophy had been made ambiguous and incoherent, allowing loose interpretation. This ambiguity prompted Nazi interpreters to choose a context that supported Nazi literature and prophesy. Evidence that Nietzsche's work was interpreted as anti-Semitic can be found in a letter Nietzsche wrote to Elisabeth [in 18xx], concerning her affiliation with the anti-Semitic movement leader, Bernard Förster (Kaufmann, 45): It is a matter of honor to me to be absolutely clean and unequivocal regarding anti-Semitism, namely opposed, as I am in my writings… I have been persecuted [pursued; verfolgt?] in recent times with letters and Anti-Semitic Correspondence sheets; my disgust with this party … is as outspoken as possible, but the relation to Förster, as well as the after-effect of my former anti-Semitic publisher Schmeitzner, always bring the adherents of this disagreeable party back to the idea that I must after all belong to them… According to Kaufmann Bernard Förster was a "prominent leader of the German anti-Semitic movement" who's racial and anti-Semitic views were received "second hand from Wagner" (Kaufmann, 46f). Förster and Elisabeth married in 1885, which prompted Elisabeth to build an anti-Semitic bias into her brother's work. Elisabeth's censorship was possible by her "monopolizing of the manuscript material," allowing her to withhold Ecce Homo from publication until 1908, and to publish selections from Nietzsche's 1880s notebooks as The Will to Power in 1901. The content of Ecce Homo was critical to distinguishing Nietzsche's philosophy from being Darwinist (Kaufmann, 8): [Nietzsche's] conception of the overman – as different from man as man is from the ape – might in any case have supplied a Darwin-conscious age with a convenient symbol for its own faith in progress. The development, however, was aided and abetted by her [Elisabeth's] publication of Ecce Homo, which contains a vitriolic denunciation of this misinterpretation. The withholding of Ecce Homo was partly responsible for the formation of the "legend of Nietzsche" because it deprived readers of the intended context. A book that Elisabeth published to further twist Nietzsche's intentions was The Will to Power. The Will to Power was a compilation of Nietzsche's notes, and was credited as Nietzsche's magnum opus (Kaufmann, 7). Kaufmann considers the book's publication as "Nietzsche's final and systematic work blurred the distinction between his works and his notes … [which] created the false impression that the aphorism in [Nietzsche's] books are of a kind with these disjointed jottings" (Kaufmann, 6). With chapters emphasizing the importance of breeding and the need to exterminate the weak, Nietzsche's philosophy became an overcoming of the physically and racially inferior (Kaufmann, 6, 75). In addition to censorship and editing of books, Elisabeth wrote introductions to Nietzsche's various works, which established her own interpretation as the authoritative one. Her interpretation could hardly be questioned because "she was the guardian of yet unpublished material – and developed an increasingly precise memory for what her brother had said to her in conversation." Elisabeth's intellectual integrity (or lack thereof) is best illustrated by Kaufmann's citation of Rudolf Steiner, a German scholar hired by Elisabeth to teach her the philosophy of her brother (Kaufmann, 5): The private lessons…taught me this above all: that Frau Förster-Nietzsche is a complete laywoman in all that concerns her brother's doctrine…[She] lacks any sense for fine, and even for crude, logical consistency; and she lacks any sense of objectivity. …She believes at every moment what she says. She convinces herself that something was red yesterday that most assuredly was blue. We can thus infer that Elisabeth's inadequacy as an analyst of her brother, as well as her personal bias, provided a misrepresentation of Nietzsche's works. Elisabeth's involvement in politics was an attempt to resolve the financial trouble of the Nietzsche archive. Macintyre [who?] states: "Elizabeth was determined that the Archive should be made financially secure. She needed a permanent patron, someone who could ensure her future and her lifestyle, and the future of her Archive. She chose the Nazis" (Macintyre, 178). Elisabeth's friendship first began with Wilhelm Frick, a National Socialist representative and partner to Adolf Hitler, who showed interest in preserving the Archive (Macintyre, 179). Elisabeth wrote in a letter thanking Frick for his support: "I understand what Herr Hitler has found in Nietzsche – and that is the heroic cast of mind which we need so desperately" (Macintyre, 178). Elisabeth's attitude towards Hitler and Nietzsche is evident in her letter to a member of the Nietzsche Archive board: "If my brother had ever met Hitler his greatest wish would have been fulfilled…What I like most about Hitler is his simplicity and naturalness…I admire him utterly" (Macintyre, 183). Over the course of Elisabeth and Hitler's friendship, Hitler visited the Nietzsche Archive seven times, which Macintyre attributes to "the propaganda value of Nietzsche as a Nazi prophet" (Macintyre, 184). Although Hitler's visits to the Nietzsche archive document his interest in Nietzsche, did that interest originate before he began writing Mein Kampf in 1925? A historical figure who linked Hitler's and Nietzsche's philosophies was Richard Wagner (1813-1883). In Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote of his admiration for Richard Wagner, a19th century German composer from Bayreuth. Wagner was one of the intellectual precursors of thought that led to National Socialism. He had a profound impact on Hitler, who wrote in Mein Kampf (17): I was captivated. My youthful enthusiasm for the master of Bayreuth knew no bounds. Again and again I was drawn to his works, and it still seems to me especially fortunate that the most modest provincial performance left me open to an intensified experience later on. Wagner's music, and later his racist and ethnocentric ideology evidently appealed to Hitler. Wagner's impact on Nazism was profound, which justifies Hitler's statement that "to understand Nazism one must first know Wagner" (Shirer, 102). On one of Hitler's trips to the Bayreuth [in 18xx], he stopped at the Nietzsche archive in Weimar (Macintyre, 184). For Nietzsche, Wagner was "Germany's greatest living creative genius" and showed that "greatness and genuine creation were still possible" (Kaufmann, 30). Wagner was a "father substitute" for Nietzsche, who lost his father at the age of four in 1848 (Kaufmann, 33). In the posthumously published Ecce Homo (1908), Nietzsche wrote of his admiration for Wagner as a revolutionary and dangerous composer, who ventured outside the norms of music to create and explore dangerous fascinations. Nietzsche once described Wagner as "the great benefactor of my life" (Kaufmann, 31f-give original source). However, Wagner's chauvinistic, nationalistic, and racist philosophy fundamentally opposed Nietzsche's beliefs. As a result, the friendship between the two men deteriorated and finally broke in 1882. Although Nietzsche split with Wagner and voluntarily exiled himself from the emerging cultural center of Bayreuth, Elisabeth never accepted the break (Kaufmann, 37). Once Elisabeth had the property rights of Nietzsche's works, she was able to re-write history to satisfy her delusion. In a response to a letter from Hitler, cited by Kaufmann, Elisabeth summarized her exploits: "The most difficult task of my life began, the task which, as my brother said, characterized my type – i.e., 'reconciling opposites'" (Kaufmann, 46). Elisabeth's reconciliation of Nietzsche's work with Wagner's prior to the Nazi dictatorship provided the criteria Hitler would have taken interest in. Hitler's early interest in Wagner's work and attraction to Elisabeth's Nietzsche Archive suggests that Hitler may have read some of Nietzsche's works. The plausibility of Hitler's early interest in Nietzsche becomes more evident when Nietzsche and Hitler's ideological concepts are juxtaposed. The concepts and terminology Nietzsche used were not the only semblance to Hitler's philosophy, but also the ardent language involved in his polemics against contemporary morality. Two critiques of the influence of Nietzsche's language were written by Steven Aschheim and Weaver Santaniello. In Nietzsche, Anti-Semitism, and the Holocaust (1997), Steven Aschheim discusses the "issue of the radicalizing, triggering forces," which were responsible for fascists' interest in Nietzsche's work (Aschheim, 16). Nietzsche's radical use of the terms: sick, healthy, strong, weak, and species, give false implications. Take for instance the following quotation from Genealogy of Morals (III, 14): Among them, again is the most loathsome species of the vain, the lying abortions, who make a point of representing 'beautiful souls,' and perchance of bringing to the market as 'purity of the heart' their distorted sensualism swathed in verses and other bandages; the species of 'self-comforters' and masturbators of their own souls. The sick man's will to represent some form or other of superiority, his instinct for crooked paths, which lead to a tyranny over the healthy. – where can it not be found, this will to power of the very weakest? Nietzsche's "sick man" who is a part of a "species" that is characterized by its "purity of the heart" and "beautiful souls" is undoubtedly a reference to adherents of the Judeo-Christian ethic. Being that Nietzsche was Lutheran, and in light of the prevalence of anti-Semitism throughout Europe, it is simple to interpret this passage as an attack on Judaism. The Jews' "crooked path" as a means for gaining superiority and "tyranny over the healthy" clearly parallels Hitler's accusation that the Jews cleverly created democracy and Marxism. Moreover, the term "lying abortion" asserts these Jews do not deserve to live. Aschheim argues that it was Nietzsche's language that flared the imagination of the Nazi party by making all actions, regardless of their level of brutality, conceivable: Nietzsche's "vocabulary and sensibility constitutes an important (if not the only) long-term enabling precondition of such radical elements in Nazism." (Aschheim, 16). In his 1994 biography Nietzsche, God, and the Jews, Weaver Santaniello addresses the impact of Nietzsche's radical language: "Nietzsche's language is indeed violent and excessive, but not uncalculated, careless or irresponsible." However Nietzsche's extreme wording was included in the Anti-Semitic Correspondence, which Nietzsche mentioned in a letter (Santaniello, 141): Now a comic fact…I have 'influence,' very subterranean, to be sure…perhaps they 'implore' me, but they cannot escape me. In the Anti-Semitic Correspondence…my name appears in almost every issue. Although Santaniello clarifies that the meaning of Nietzsche's concepts was distorted by the Nazis, he argues that it was the violent language that described the slave revolt, and the Jews, that instigated the Nazis perversion of Nietzsche's literature (Santaniello, 31). In Nietzsche's and Hitler's works, a fundamental concept is the clash between the "whole man" and "half man." Similar terms that are oriented around this concept are: the Jew, blood poisoning, spiritual convictions, and blond beast. These terms define both Nietzsche and Hitler's determinants and restraints to achieving a new order, in addition to the clash between "whole men" and "half men." Nietzsche refers to the "whole man" and "half man" mostly as master morality and slave morality. The slave morality consists of noble morality and slave morality [huh?]. Noble morality was the belief that the majority of human beings are led by insatiable, destructive, human desires, and it is the noble's obligation to instill fear in order to protect civilization from a state of anarchy and chaos. As Nietzsche wrote in the Genealogy of Morals (III 10): The contrary is the case when we come to the aristocrat's system of values: it acts and grows spontaneously, it merely seeks its antithesis in order to pronounce a more grateful and exultant 'yes' to its own self;- its negative conception, 'low,' 'vulgar,' 'bad,' is merely a pale born foil in comparison with its positive and fundamental conception (saturated as it is with life and passion), of 'we aristocrats, we good ones, we beautiful ones, we happy ones.' Nietzsche described the nobles as seeing the majority of mankind as contemptible and ignorant, and themselves as the protectors of all that is good. On the other hand, slave morality was the belief that the majority of human beings are good and it is the nobles who are oppressive and vicious, thus contemptible beings. "The revolt of the slaves in morals begins in the very principle of resentment becoming creative and giving birth to values – a resentment experienced by creatures who, deprived as they are of the proper outlet of action, are forced to find their compensation in an imaginary revenge" (Nietzsche, Genealogy III 10). Thus it is through values that slaves make nobles feel resentment towards themselves, and it is the slaves who prevent mankind from reaching its potential. Slave and noble morality differ from master morality because they do not operate in the interest of self-preservation. Rather, they attempt to help one another. In The Will to Power, Nietzsche described the resulting "mediocrity" as a seducer, which he defined as "liberal" (Nietzsche, Will, 864). The strong have come to see themselves as contemptible, causing them to be weak and indecisive, hence their "mediocrity." This liberal perspective provides the clever slaves with an advantage over the strong, who thus reject their own strengths as ugly and subhuman. Both Hitler and Nietzsche refer to the clever slaves as the Jews. Hitler's Mein Kampf is an attack on the Judeo-Christian ethic, as is The Genealogy of Morals. Nietzsche addressed the Jews as being responsible for the slave revolt and victory over the master race (I 7): In the context of the monstrous and inordinately fateful initiatives which the Jews have exhibited in connection with the most fundamental of all another occasion (Beyond Good and Evil, Aph. 195) – that it was, in fact, with the Jews that the revolt of the slaves begins in the sphere of morals; that revolt which has behind it a history of two millennia, and which at the present day has only moved out of our sight, because it has achieved victory. It is easier to understand the Judeo-Christian ethic, in respect to Nietzsche, as a mirror with which the slaves use to make the masters feel guilty and self-hating. By making the master empathize with the Slave, the master resents the qualities that make him strong, that is, actions that are in the interest of self-preservation. Nietzsche identifies the slave with the Jew because they are responsible for the existence of the Judeo-Christian ethic. In Mein Kampf, Hitler also identifies Jews as the creators of moral slavery (Hitler, 178): The most unbeautiful thing there can be in human life is and remains the yoke of slavery. Or do these schwabing [?] decadents view the present lot of the German people as 'aesthetic'? Certainly we don't have to discuss these matters with the Jews, the most modern inventors of this cultural perfume. Their whole existence is an embodied protest against the aesthetics of the lord's image. Hitler describes Jews as slaves in the same sense as Nietzsche. Hitler points to "slavery" as the ugliest aspect of human life in the past and present, while linking the Jews and their influence (i.e. "cultural perfume") to the deterioration of values, which is manifest in the "schwabing decadents." Hitler describes the product of the cultural perfume as the "whole man" and "half man," which are terms used to describe individuals motivated by self-preservation, as opposed to those whose individual guilt is ridden by morality, seeking to help others. Hitler defined the "degeneration" of man in these terms (Hitler, 30): This uncertainty is only too well founded in our own sense of guilt regarding such tragedies of degeneration; be that as it may, it paralyzes any serious and firm decision and is thus partly responsible for the weak and half-hearted, because hesitant, execution of even the most necessary measures of self-preservation. Hitler's use of the "weak and half-hearted" appears frequently throughout Mein Kampf, often in conjunction with Jews or the influence of the Jewish conspiracy. For example, Hitler accused the Jews of being responsible for both democracy and Marxism, the two forms of government founded to appease the collective over the strong individual. The ineffectiveness of Weimar's democracy and the threat of Bolsheviks following World War I provided the context with which Hitler saw them clash as weak, irreconcilable ideologies designed to profit Jews (Hitler 173f). For Nietzsche and Hitler, the Judeo-Christian ethic caused an individual to split himself into two opposing forces: the interest of the collective (i.e. "half man" or slave morality) and the interest of self-preservation (i.e. "whole man" or master morality). The dominating force makes an individual either confident and strong, or guild-ridden and indecisive. For both Nietzsche and Hitler, the latter prevailed throughout Europe. In The Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche described the state of Europe (I 9): The 'masters' have been done away with; the morality of the vulgar man has triumphed. This triumph may also be called a blood-poisoning (it has mutually fused the races)…Everything is obviously becoming Judaised, or Christianised, or vulgarized… Nietzsche's use of the phrase "blood poisoning" to describe the effect of the Judeo-Christian ethic is similarly stressed by Hitler. In multiple sections of Mein Kampf, including: "Consequence of Jew Egotism," the "Sham Culture of the Jew," "The Jew a Parasite," "Jewish Religious Doctrine," "Development of Jewry," and many others, Hitler accused the Jewish people as belonging to a race that lacked any culture and manipulated others to get the strength to survive (Hitler, 301). And because they are a primitive herd, they are limited in their impulses to surpass the "individual's naked sense of self-preservation" through self-sacrifice (Hitler, 301). With their blood they contaminate the higher races and weaken the culture of the Aryan race: The Jew "poisons the blood of others, but preserves his own," and being aware of his ability to degenerate the high nobility, the Jew "systematically carries on this mode of 'disarming' the intellectual leader class of his racial adversaries. In order to mask his activity and lull his victims, however, he talks more and more of the equality of all men without regard to race and color" (Hitler, 316). Hitler wrote that men did not die from wars, but rather from the lack of resistance created by pure blood; and it was blood mixture that caused the deterioration of culture (Hitler, 296). As a foundation for resolution to the deterioration of culture, both Hitler and Nietzsche argued the essential need of spirituality. Hitler argued: "For, once the actual and spiritual conqueror lost himself in the blood of the subjected people, the fuel for the torch of human progress was lost! Just as, through the blood of the former masters … they shine through all the returned barbarism…" (Hitler, 292). The Aryan conqueror spirituality was a pivotal aspect of the figure, and introduced the importance of spiritual convictions. Nietzsche wrote of the importance of a spiritual impetus in achieving independence (Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 984): Greatness of soul is inseparable from greatness of spirit. For it involves independence; but in the absence of spiritual greatness; independence ought not to be allowed, it causes mischief, even through its desire to do good and practice 'justice' small spirits must obey – hence cannot possess greatness. Nietzsche argued that an individual must have a spiritual conviction if the individual is to have independence and reach a status of greatness. Hitler agreed, and extended the prerogative of spiritual conviction to the use of authority and violence (Hitler, 171): Only in the study and constant application of force lies the very first prerequisite for success. This persistence, however, can always and only arise from a definite spiritual conviction. Any violence which does not spring from a firm, spiritual base, will be wavering and uncertain….It emanates from the momentary energy and brutal determination of an individual, and is therefore subject to the change of personalities and to their nature and strength. The use of violence was essential for the realization of Hitler's ideology. While Nietzsche's opinions of slave morality and noble morality are resolved by self-overcoming, Hitler's resolution is in alienating the manifestations of slavery (i.e. Jews) and destroying them. The difference between the two excerpts dealing with spiritual convictions represent this difference; Nietzsche deals with greatness of the soul (i.e. intangible obstacles and mental transvaluation), while Hitler speaks of violence and "brutal determination" (i.e. revaluation, persecution, and destruction). A symbol of greatness and raw human potential are used similarly in Mein Kampf and Nietzsche's works: the idea of the blond beast. The blond beast was a man who was unrestrained by values, and therefore had never experienced resentment, which was constructed by the weak for revenge against the strong. For Nietzsche, the slave's values have labeled the impulses of man as evil, and thus the slave has glorified passivity. Moreover, action for the slave only becomes good when it is a reaction (Nietzsche, Genealogy III 10): "Complete men … exuberant with strength, and consequently necessarily energetic, they were too wise to dissociate happiness from action – activity becomes in their minds necessarily counted as happiness." Nietzsche's "complete man," synonymous with Hitler's "whole man," represents a version of the "blond beast," or "beast of prey," who returned to the wilderness to free himself from the peace of society. Nietzsche associated the "magnificent blond brute" with the Roman, Arabic, Germanic, and Japanese nobility, who were all "rampant for spoil and victory." Nietzsche's blond beast, which becomes associated primarily with Germans when it resurfaces as the "blond Teuton beast," is mankind's hope to reach its full potential (Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, III 10). However, unrestrained impulses are likely to lead to destruction, which Nietzsche acknowledges as a trade-off. Nietzsche defended the horror by arguing that it is better to be afraid of the impulsive brute than surrounded by the immune, "the dwarfed, the stunted, and envenomed" (Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, III 10). In other words, Nietzsche argued it is better to chance the occurrence of horror than castrate man's impulsive nature. Hitler's blond beast represents the old Aryan master race, which he calls the Aryan conqueror. Hitler believed the pure Aryan conqueror and its race was responsible for all human culture (Hitler, 290). Through the principle of resentment the Aryan race fell from its glory, tricked and poisoned by the clever Jew. Hitler's idea of the Jewish conspiracy is a case of the Jews using the principle of resentment on the Aryan master race through democracy, Marxism, and blood poisoning. Before its undermining, the blue eyed, blond Aryan conqueror was believed to have acted in the interest of his own self-preservation; and thereby attained the status of master through his blood and subjugation of weaker races (Hitler, 296). He was a "whole man" who could successfully achieve high culture and happiness. Hitler described "the weakness and half-heartedness of the power taken in old Germany" as a terrifying sign of decay from this master ancestor (Hitler, 257). Hitler believed the "whole man," the Aryan conqueror, was to inherit the world: "If the power to fight for one's own health is no longer present, the right to live in this world of struggle ends. This world belongs to the forceful 'whole' man and not to the weak 'half' man" (Hitler, 257). Through his interest in self-preservation and brutality, Hitler prophesized that the Aryan conqueror would return high culture to the earth (Hitler, 297). Nietzsche and Hitler shared beliefs in transvaluation, interest of self-preservation, and prophesies of an age of barbarism followed by a new order of blond conquerors, or supermen. These concepts set the foundation for anti-democracy and universal equality. In further discussion of clashing moralities, Nietzsche discussed the concept of the "soul" by using the terminology "lambs" and "birds of prey" to symbolize the slaves and nobles (Genealogy, III 10). He argued the soul was the source of identification for the slave because it suggested there was a universal commonality – that all human beings are equal. This idea corrupted action in the interest of self-preservation, which had now been defined as an attack on fellow brethren. Nietzsche was nauseated by this and expressed the belief that the soul "has perhaps proved itself the best dogma in the world simply because it rendered possible to the horde of mortal, weak, and oppressed individuals of every kind…the interpretation of weakness as freedom, of being this, or that, as merit" (Genealogy III 10). By glorifying the blond beast, Nietzsche illustrated his disgust with the concept of universal equality and democracy. Consistent with Nietzsche's condemnation of identification with the weak, Hitler believed that democracy and equality, while praised in America and Europe, were constrictive and degenerative. Hitler wrote: "social activity must never and on no account be directed toward philanthropic flim flam, but rather toward the elimination of the basic deficiencies in the organization of our economic and cultural life that must – or at all events can – lead to the degeneration of the individual" (Hitler, 30). In place of Nietzsche's blond beast, Hitler identified the blond, blue-eyed Aryan race as the embodiment of high culture, overshadowing the weak and slavish roots of democracy. The fact that Nietzsche's blond beast and Hitler's blond Aryan conqueror shared a dislike for democracy does not suggest a relationship. Especially considering the ineffectiveness of the Weimar democratic system, which Hitler experienced firsthand. However, the similar terminology begs the issue of causality to be further assessed. While the slave moralities clash, Nietzsche prophesed that a new morality would form and harness the human "will to power," and this man will be the Overman, or Superman. Nietzsche described the terribleness that follows the questioning of values and the creation of the superman: "Man is beast and superbeast; the higher human is inhuman and superhuman: these belong together. With every increase of greatness and height in man, there is also an increase in depth and terribleness" (Will to Power, 1027). Nietzsche justified terror with the belief that it would bring a higher state for mankind. But what is the superman other than terribleness? Shirer cited Nietzsche's explanation of how the superman was prophesized to dominate the world (Shirer, 111): The strong men, the masters, regain the pure conscience of a beast of prey; monsters filled with joy, they can return from a fearful succession of murder…when a man is capable of commanding, when he is by nature a 'master,' when he is violent in act and gesture … to judge morality properly, it must be replaced by two concepts borrowed from zoology: the taming of a beast and the breeding of a specific species. Nietzsche's prophecy calls for a master to maintain beasts of prey through breeding and transvaluation, which was essentially Hitler's course of action following his appointment to chancellor. In The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William Shirer cited an aphorism from The Will to Power that more clearly defined the Superman's qualities: "A daring and ruler race is building itself up…the aim should be to prepare a transvaluation of values for a particular strong kind of man, most highly gifted in intellect and will. This man and the elite around him will become 'lords of the earth'" (Shirer, 101f). Shirer analyzed this quotation with respect to how Nietzsche affected Hitler and the content of Mein Kampf: Such rantings from one of Germany's most original minds must have struck a responsive chord in Hitler's littered mind. At any rate he appropriated them for his own – not only the thoughts but the philosopher's penchant for grotesque exaggeration, and often his very words. 'Lords of the Earth' is a familiar expression in Mein Kampf. That in the end Hitler considered himself the superman of Nietzsche's prophesy can not be doubted. In Mein Kampf, Hitler also emphasized the importance of questioning values and the necessary terror to transform the blood-poisoned state of Germany into an Aryan utopia. Hitler wrote, "Only when an epoch ceases to be haunted by the shadows of its own consciousness of guilt will it achieve the inner calm and outward strength brutally and ruthlessly to prune off the wild shoots and tear out the weeds" (Hitler, 30). If Hitler's Mein Kampf was partly a derivative of Nietzsche's work, the brutality Hitler referred to is the terribleness which Nietzsche described; it is the necessary destruction to refine the masses. Proposal for resolution of the slave's disease (i.e. Judeo-Christian ethic and blood poisoning) was implied by both Hitler and Nietzsche to be annihilation. Hitler believed in the possibility of the pacifistic-humane idea "when the highest type of man has previously conquered and subjected the world to an extent that makes him the sole ruler of the earth" (Hitler, 288). Consistent with this thought, annihilation of the slave was essential. To fight the weight of diseased and weak human beings, Hitler sought to ruthlessly apply "Nature's stern and rigid laws" (Hitler, 289). His philosophy was "Those who want to live, let them fight, and those who do not want to fight in this world of eternal struggle do not deserve to live" (Hitler, 289). In The Will to Power, a number of aphorisms present solutions to the decadence of Europe and the World. In aphorism 862, Nietzsche proposes a doctrine of breeding and annihilation: A doctrine is needed powerful enough to work as a breeding agent: strengthening the strong, paralyzing and destructive for the world weary. The annihilation of the decaying races. Decay of Europe.-The annihilation of slavish evaluations.-Dominion over the earth as a means of producing a higher type.-The annihilation of the tartuffery called 'morality.' The annihilation of suffrage universel; i.e. the system through which the lowest natures prescribe themselves as laws for the higher.-The annihilation of mediocrity and its acceptance (The one sided, individuals – peoples; to strike for fullness of nature through the pairing of opposites: race mixture to this end). The new courage – no a priori truths… This proposal of annihilation highly compares to Hitler's policies of extermination. Both Hitler and Nietzsche assert that the host of the slavish disease of values and decay is the clever Jew, the need for a spiritual base of independence of thought and action, the revaluation of strong and weak, and the annihilation of the slaves. By juxtaposing Hitler's work and Nietzsche's, the groundwork of Mein Kampf is clearly a literal interpretation of Nietzsche's work. The underlying themes in Nietzsche and Hitler's philosophies are the importance of impulses and action for self-preservation, the danger of the clever Jew (i.e. the slave who has re-valuated strong as evil and weak as good), and the prophesy of a new type of man that will question the Jewish values and return the glory of the blond beast. Although Nietzsche's reference to slaves and masters are references to personified moralities, the themes and language are strikingly consistent with the language and terminology used by Hitler in Mein Kampf. Nietzsche's close relationship with Richard Wagner, Elisabeth's reconciliation of Nietzsche's work with Wagner's racist ideology, and Hitler's praise of Wagner's work suggests that Hitler may have read Nietzsche's work. Elisabeth's political involvement with the Nazis, and Hitler's multiple visits to the Nietzsche archive suggest Hitler's direct awareness and interest in Nietzsche's philosophy. And finally, the radical content and similar terminology used by the Nietzsche and Hitler implies that Nietzsche's influence in 20th century Germany may have extended to the Führer, as a narcissistic discovery of the Superman. In the conclusion of Mein Kampf Hitler wrote (Hitler, 688): A state which in this age of racial poisoning dedicates itself to the care of its best racial elements must some day become lord of the earth. May the adherents of our movement never forget this if ever the magnitude of the sacrifices should beguile them to an anxious comparison with the possible results. |

|

Works Cited: Primary Sources

Works Cited: Secondary Sources

|