Main Text (back

to top)

When thinking of resistance, one might usually think of more military

actions such as bombing railroads and assassination attempts on political

leaders. But what could someone whose every right was stripped from them

when they were forced into ghettos or concentration camps do to defy their

oppressors? Even in the most desperate and hopeless of situations, women

suffering under the horror of the Holocaust found many ways to resist

the Nazis. Resistance included any course of action that directly rebelled

against Nazi laws, policies, and ideology. In the Jewish ghettos and concentration

camps that could mean maintaining a sense of humanity, providing means

for people to escape and hide, plotting mass escapes, dying with dignity,

or remembering and telling the world about the horrible events that occurred.

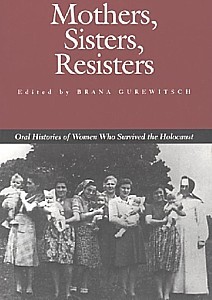

The accounts of the women below are taken from the book edited by Brana

Gurewitsch called Mothers, Sisters, Resisters: Oral Histories of Women

Who Survived the Holocaust. The book contains the oral histories

of over a twenty-five women who experienced the Holocaust. The women chosen

for this project represent the deferent ways women resisted in the Jewish

ghettos and concentration camps.

One woman resisted the intolerable cruelty and oppression faced in the

ghetto by devoting herself entirely to goodness and humanity. Dr.

Anna Braude-Hellerowa was the director of the children’s hospital in the

Warsaw ghetto, and she completely devoted her energy to the children,

even the ones with no hope of recovery. On many occasions she put the

life of her patients before herself. For example, when friends of hers

outside the ghetto arranged a hiding place for her, she refused to go.

Later, Dr. Braude-Hellerowa was given roughly twenty-five "life-passes"

to give to members of her staff so that they would be exempt from the

next selection. This was a difficult decision seeing that she had a staff

of over two hundred people. She did not give a single pass to any of her

family or friends or close colleagues. Instead she gave them to the youngest

members of her staff. Bronislawa Feinesser, who received one of these

life passes, said of Dr. Braude-Hellerowa: "She was an absolutely

unusual woman." During a period that experienced a collapse of humanity,

the ability of this incredible woman to maintain a sense of absolute selflessness

and humanity demonstrated her role as a resister.

Others saw dignity in death as a type of direct opposition to the Nazis.

Dr. Adina Blady Szwajger also worked as a doctor in the Warsaw

ghetto. Knowing that everyone sent to Treblinka died, she made

the decision to administer morphine to her young patients so that they

could die peacefully in their sleep. The Germans may have still in a sense

taken their lives, but they were not allowed to strip these children of

their human dignity.

Acts of resistance in the ghettos were not always actions of individuals

alone. In some cases there were complex groups working to help the Jews.

Bronislawa Feinesser, who later took the alias Marysia from genuine

identity papers, worked for one of these groups known as the Bund

organization. However her history of resistance begins before that. Marysia

was born in Warsaw of a middle-class Jewish family. Her family spoke Polish

in their home, not Yiddish, and she attended Polish primary school. She

was very assimilated into Polish culture and society, and did not have

the most striking characteristics that people of the time determined as

Jewish. While in the ghetto, her first act of defiance was attending an

underground medical school. She did not allow her education and personal

growth to be stopped by an outside force. Marysia also worked as a nurse

in the hospital and was frequently given a pass out of the ghetto to do

hospital administration work. While in the Aryan part of Warsaw, she would

smuggle food and weapons in and out of the ghetto, and establish hiding

places for escapees. While being interviewed about these dangerous missions

Marysia claimed, "Today I would be very scared. At that time when

I was twenty something; I wasn’t scared. I wanted to do it. I wanted to

be active, to help people, and I had my group that needed me to do this."

Marysia showed absolute bravery, knowing that the consequences of smuggling

weapons into the ghetto would be severe, even mortal. As the situation

in the ghetto intensified and more and more trains departed for concentration

camps, she decided to break out of the ghetto and live permanently in

the Aryan portion of the city. She was able to do this because she was

fearless and she did not have distinctly Jewish characteristics. Her sister,

who also broke out, struggled more because even though she looked more

Aryan, she had a fearful look in her eyes which gave her away. During

this time Marysia became actively engaged in the Bund organization. Her

duties included finding hiding places, organizing false documents, distributing

money and paying rent to land lords. The room that she lived in was also

the headquarters for the Bund group, and she and her roommate disguised

themselves as prostitutes to legitimize having many different men come

to their room.

Marysia did many risky and dangerous feats in order to help strangers

and she did it without any personal gain. Others did help others but also

profited greatly from it. Can they too be considered resisters? She describes

just such a time when she was placed in such a conflict of conscience.

She came into contact with the wife of a Polish officer whose husband

was living in a faraway camp. The woman took in and hid a lot of Jews,

but she also took a lot of money for each person she hid. After the war,

this woman came to Marysia asking for a certification saying that she

rescued Jews. Marysia says, "That was true, but the other part was

that she took a lot of money. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want

to have this on my conscience because I realized that that somehow she

did this for money." In the end, she made someone else make the decision

and they decided to give the Polish woman the certification. Though this

woman was definitely helping herself first, she prevented the Gestapo

from taking the Jews she hid. It is just another example of how far the

spectrum of resistance reached.

Even though the situation of the people in the ghetto was bleak and miserable,

it was not as hopeless as imprisonment in the concentration camps. However,

even in the most dehumanizing and desperate environment, people did. Anna

Heilman and her sister Estusia were among the last deportees out of the

Warsaw ghetto when they were sent to Auschwitz in September 1943.

There they were assigned to work in a munitions factory in the room called

the pulverraum, the only place in the camp where prisoners handled

gunpowder. Their resistance began as a small group of girls who grew to

trust each other and gathered strength from one another by talking about

things outside the camps. They knew of rumors of a plan for a mass escape

and decided to contribute their resources. Rose Meth also worked

with the Heilman sisters in the pulverraum, and when asked

if she would help she recalls, "I agreed right away because it gave

me a way to fight back. I felt very good about it, and I didn’t care about

the danger." This way of thinking mirrors what most resisters in

the concentration camps thought. If they were going to die anyway, they

should die fighting. Not everyone in the camp felt the same way. Another

girl, when asked if she would ever do anything that would aid in escaping

if given the chance, refused. Later she admitted to Rose Meth, "I

was afraid that I would not be strong enough under duress, if they would

catch me, whether I could withstand pain." Fear and intimidation

were powerful and effective weapons against rising up against the Nazis.

The girls slowly smuggled gunpowder to the men who worked, the crematoria,

who would then make homemade grenades with shoe polish tins. Since three

girls working together could only collect two spoonfuls a day of gunpowder,

it took eight months for the bombing of the crematoria to take place.

The uprising occurred on October 7, 1944. While it successfully blew up

a crematorium and slowed the death machine, no one escaped. Estusia and

Rose were beaten and interrogated by the S.S. because they worked with

the gunpowder. However they would not give up any names of their conspirators,

resisting even under extreme physical pain.

Rose Meth practiced resistance in another form as well. Her father wanted

her to "remember what was happening, to be able to tell the world,

so the world would know of the heinous crimes the Germans committed."

Rose would exchange food for paper in order to write notes while in Auschwitz.

This written account and the oral accounts of so many survivors acted

as agents of resistance then and even still today against hate and atrocities.

These women took very different actions in order to resist according

to their abilities. However, they share the most important quality; they

all consciously decided to fight against the fate the Third Reich attempted

to force upon them. Some lived with honor, and others died maintaining

it. |