Notes

(back to top)

[1] Alvin Rosenfeld, Imagining Hitler (Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 1985), 94-95, quoted in Kenneth L. Work, "A Separation

From Reality: The American Attitudes Toward Adolf Hitler from 1923

to 1995" (Ph.D. diss., Georgia State University, 1996), 213.

[2] Throughout this paper, any reference to youth indicates the

views of elite college educated students, as this was the sector of

the population that I focused on. Because only four college newspapers

were utilized, this thesis serves as only one attempt to find a consensus

of student opinion on Hitler.

[3] Work, 4. See also Daniel Shepherd Day, "American Opinion

of German National Socialism, 1933-1937" (Ph.D. diss., University

of California, Los Angeles, 1958), 7.

[4] Michael Zalampas, Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich in

American Magazines, 1923-1939 (Ohio: Bowling Green State University

Popular Press, 1989), 217.

[5] Liesel Ashley Miller, "Perceptions of the Personality of

Adolf Hitler in American Periodicals, 1939-1941" (Master's thesis,

Mississippi State University, 1994), 5.

[8] Miller, 8. See also abstract of Roberta Siegel, "Opinions

on Nazi Germany: A Study of Three Popular American Magazines, 1933-1941"

(Ph.d. diss., Clark University, 1950).

[10] "America's Grade on 20th Century European Wars,"

New York Times (December 3, 1995), 5. This data was based

on a test given by the Educational Excellence Network with the National

Assessment of Educational Progress. The results were published in

Diane Ravitch and Chester E. Finn Jr., What Do Our 17 Year Olds

Know? (Harper and Row, 1987), quoted in Work, 187-188.

[12] Toni McDaniel, "A ‘Hitler Myth?' American Perception of

Adolf Hitler, 1933-1938," Journalism History 17 (1990-1991):

48.

[13] Kenneth Work was the only scholar who actually directly

included university students' views in his research by surveying core

curriculum history courses at Georgia State University. "The overall

objective…of the research was to determine how college students perceived

Adolf Hitler, using a research technique that encourages students

to give free and uninhibited responses to questions." Work, who succeeds

in including the voice of youth, still ignores the youth perceptions

of Hitler during the years he was in power, as his research was conducted

between the end of 1991 and the summer of 1995, some fifty years after

Hitler's death.

[16] Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1993), xviii.

[19] The Daily Californian, January 30, 1933.

[20] The Daily Californian, January 31, 1933.

[21] California Daily Bruin, January 31, 1933.

[22] Yale Daily News, February 1, 1933.

[23] Yale Daily News, February 2, 1933.

[24] The Harvard Crimson, February 14, 1933.

[25] The Daily Californian, January 31, 1933.

[26] The Daily Californian, February 7, 1933.

[27] Yale Daily News, February 3, 1933.

[30] Jackson J. Spielvogel, Hitler and Nazi Germany A History

(New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1996), 70-71.

[31] The Daily Californian, March 6, 1933.

[32] California Daily Bruin, March 8, 1933.

[33] Yale Daily News, March 7, 1933.

[34] The Harvard Crimson, March 8, 1933.

[38] M. Domarus, Hitler, Reden und Proklamationen 1932-1945

(Wiesbaden, 1973), 248-251, quoted in Ian Kershaw, The ‘Hitler

Myth': Image and Reality in the Third Reich (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1987), 234.

[39] The Daily Californian, April 3, 1933.

[40] The Daily Californian, April 4, 1933.

[41] California Daily Bruin, March 30, 1933.

[42] The Harvard Crimson, March 31, 1933.

[43] The Harvard Crimson, April 10, 1933.

[45] "All Fools Day," Time, April 10, 1933, 23; "Nazis

Heed an Indignant World," Newsweek, April 8, 1933, 17; "Co-ordination,"

Time, April 17, 1933, 17; The Nation, April 19, 1933,

430, quoted in Zalampas, 31.

[47] Frank H. Simonds, "Europe Moves Toward War," Harper's

Magazine 167 (June 1933): 1-11, quoted in Work, 86-87.

[48] Yale Daily News, October 16, 1933.

[49] The Daily Californian, October 16, 1933; The

Harvard Crimson, October 16, 1933.

[50] The Daily Californian, October 17, 1933.

[51] The Daily Californian, October 17, 1933.

[52] The Daily Californian, October 16, 1933.

[53] The Harvard Crimson, October 24, 1933.

[54] Eugene Bacon, "American Press Opinion of Hitler, 1932-1937,"

(Master's thesis, Georgetown University, 1948), 41.

[55] Springfield Republican, October 16, 1933,

quoted in Bacon, 41.

[56] "America, the Allies, and Hitler," The Nation, November

1, 1933, 499, quoted in Zalampas, 41.

[57] Kershaw,

63. See BAK, R18/5350, and, for investigations into complaints of

electoral irregularities, Fos. 95-10, 107-22. See also M. Broszat,

The Hitler State, London, 198, pp. 91-92. A detailed analysis

is provided in K.D. Bracher, F. Shulz, and W. Sauer, Die nationalsocialistische

Machtergreifung, Ullstein edn., Frankfurt a.M. 1974, i. 480ff.

[58] The

Daily Californian, October 19, 1933.

[59] Yale Daily News, November 13, 1933.

[60] The Harvard Crimson, November 14, 1933.

[61] Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 13, 1933;

Chicago News, November 14, 1933, quoted in Bacon, 52.

[63] Buffalo News, November 14, 1933; Washington

News, November 14, 1933; Baltimore Sun, November 13,

1933, quoted in Bacon, 52.

[64] "Effective Political Machine and One-party Ballot Bring

Expected Nazi Landslide," Newsweek, November 18, 1933, 13;

"Kämpfet Mit Uns," Time, November 20, 1933,19; "The Third Reich

Votes," The New Republic, November 22, 1933, 38, quoted in

Zalampas, 42.

[65] California Daily Bruin, August 3, 1934.

[66] John W. Wheeler-Bennett, The Wreck of Reparations

(London: Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1933), quoted in Bacon, 79.

[67] "Deutsch Ist Die Saar!," Time, January 7, 1934,

18-19, quoted in Zalampas, 63. A "ja vote" meant a vote in

favor of reuniting the Saarland with Germany.

[68] California Daily Bruin, November 11, 1934.

[69] California Daily Bruin, November 11, 1934.

[70] California Daily Bruin, March 18, 1934.

[71] The Daily Californian, January 17, 1935.

[72] The Harvard Crimson, March 12, 1934.

[73] Yale Daily News, March 6, 1935.

[74] The Daily Californian, March 20, 1935.

[75] The Harvard Crimson, May 3, 1935.

[79] The Daily Californian, September 16, 1935.

[81] New York Post, September 17, 1935; reprinted

in the Philadelphia Record, September 18, 1935, quoted

in Bacon, 125.

[82] The Harvard Crimson, November 5, 1935. William

J. Bingham, the Chairman of the Field and Track Committee, wrote this

article explaining how the International Olympic Committee operates

and how the American Olympic Committee came to accept an invitation

to the 1936 Games. He assured the Harvard students that the possible

Nazi persecution of Jews has no bearing on America's participation

in the Olympics.

[83] The Harvard Crimson, October 24, 1935.

[84] The Harvard Crimson, November 4, 1935.

[85] The Harvard Crimson, November 4, 1935.

[86] The Harvard Crimson, November 4, 1935. From the

Editor's Note.

[87] California Daily Bruin, December 5, 1935.

[88] California Daily Bruin, February 20, 1936.

[89] Richard D. Mandell, The Nazi Olympics (New York:

Macmillian & Co., 1972), 68-82, quoted in Work, 105.

[90] "America and the Olympics," The New Republic, November

6, 1935, 357-358; The New Republic, December 18, 1935, 456,

quoted in Zalampas, 77-78.

[93] Yale Daily News, March 9, 1936.

[96] California Daily Bruin, March 9, 1936; The Daily

Californian, March 9, 1936; Yale Daily News, March 9, 1936.

[97] California Daily Bruin, March 10, 1936.

[98] California Daily Bruin, March 11, 1936.

[99] The Daily Californian, March 12, 1936.

[100] The Daily Californian, March 31, 1936.

[101] The Daily Californian, March 30, 1936; California Daily

Bruin, March 31, 1936

[102] The Daily Californian, March 30, 1936.

[103] The Harvard Crimson, May 6, 1936.

[104] Yale Daily News, March 5, 1936.

[105] Yale Daily News, March 11, 1936.

[106] Yale Daily News, March 5, 1936.

[107] Yale Daily News, March 10, 1936.

[108] The Daily Californian, March 11, 1936.

[109] California Daily Bruin, April 21, 1937.

[110] California Daily Bruin, April 23, 1937.

[111] The Harvard Crimson, April 21, 1937.

[112] The Harvard Crimson, April 21, 1937.

[113] The Harvard Crimson, February 11, 1938.

[114] California Daily Bruin, January 5, 1938.

[115] California Daily Bruin, January 12, 1938.

[116] The Daily Californian, February 1, 1938.

[117] The Daily Californian, January 25, 1938.

[118] Yale Daily News, March 15, 1938.

[119] Yale Daily News, March 16, 1938.

[120] Yale Daily News, April 15, 1938.

[121] Yale Daily News, April 25, 1938.

[123] Dietrich Orlow, A History of Modern Germany 1871-Present

(New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999), 180.

[125] Yale Daily News, March 14, 1938.

[126] Yale Daily News, March 14, 1938.

[127] Yale Daily News, March 14, 1938.

[128] California Daily Bruin, March 16, 1938.

[129] The Harvard Crimson, March 15, 1938.

[130] California Daily Bruin, March 16, 1938; The

Daily Californian, March 5, 1938; The Harvard Crimson,

March 15, 1938; The Harvard Crimson, March 17, 1938.

[132] "Hull Voices U.S. Anxiety Over ‘Gangster' Nations," Newsweek,

March 28, 1938, 9-10, quoted in Zalampas, 140.

[136] The Daily Californian, September 13, 1938.

[137] The Harvard Crimson, October 15, 1938.

[138] The Daily Californian, September 20, 1938.

[139] The Daily Californian, September 12, 1938.

[140] The Daily Californian, September 12, 1938.

[141] The Daily Californian, September 20, 1938.

[142] The Daily Californian, September 1, 1938.

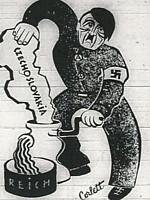

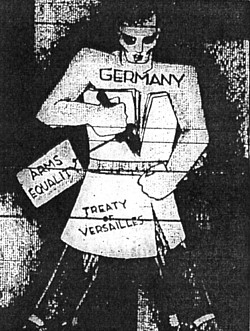

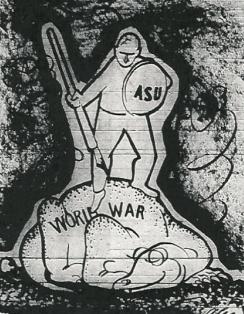

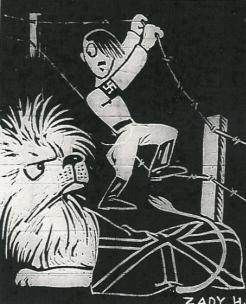

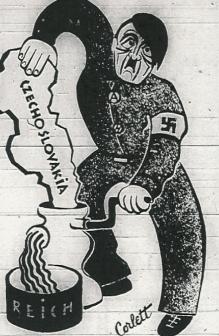

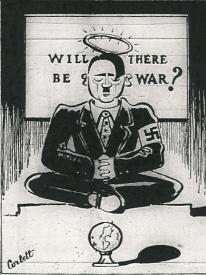

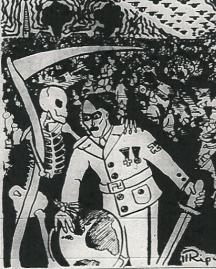

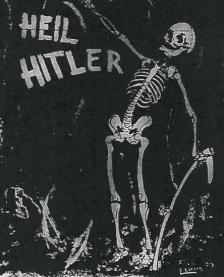

[143] Depicted in Orlow, 184. For a further discussion of

David Low's political cartoons of Hitler see Timothy Benson, "Low

and the Dictators." History Today (March 2001): 35-41.

[144] Yale Daily News, October 1, 1938.

[145] The Harvard Crimson, September 24, 1938.

[146] The Harvard Crimson, September 24, 1938.

[147] The Harvard Crimson, September 27, 1938.

[148] California Daily Bruin, September 26, 1938.

[149] Carl J. Frederich, "Edward Benes," The Atlantic Monthly,

September 1938, 357-365, quoted in Zalampas, 157.

[150] "The Great Surrender," The New Republic, September

28, 1938, 200-201; "Deathbed Repentance," The New Republic,

October 5, 1938, 225-226; "The Great Betrayal, The Nation,

September 24, 1938, 284-285; Vladimir Pozner, "Hitler Wants Skoda,"

The Nation, September 24, 1938, 287-288; Oswald G. Villard,

"More Parallel Action," October 1, 1938, 352; The Nation, October

1, 1938, 309; "If Hitler Has His Way," The Nation, October

1, 1938, 312-313; John Gunther, "Interim Notes on the Crisis," The

Nation, October 1, 1938, 316-317; "The World Waits," The New

Republic, October 5, 1938, 225; "Teuton and Slav," The New

Republic, October 12, 1938, 253-254; Vera M. Dean," Pan-German

Redivivus," The New Republic, October 12, 1938, 259-260, quoted

in Zalampas, 157-159. The Franco-Russian Pact was a treaty of mutual

assistance signed between France and Germany at the beginning of 1935.

[151] "Four Chiefs," Time, September 26, 1938, 15-16;

"Four Chiefs, One Peace," Time, October 10, 1938, 15-17; "What

Price Peace?," Time, October 17, 1938, 19-22, quoted in Zalampas,

158-160.

[152] Spielvogel, 206-207.

[153] The Harvard Crimson, September 30, 1938.

[154] The Harvard Crimson, October 7, 1938.

[155] The Daily Californian, October 17, 1938.

[156] California Daily Bruin, October 3, 1938.

[157] The Daily Californian, October 17, 1938.

[158] Yale Daily News, October 3, 1938.

[159] Yale Daily News, October 3, 1938.

[160] The Harvard Crimson, September 28, 1938.

[163] Spielvogel, 272-273.

[164] The Daily Californian, November 15, 1938.

[165] The Harvard Crimson, November 14, 1938.

[166] California Daily Bruin, November 23, 1938.

[167] Yale Daily News, November 11, 1938.

[168] Yale Daily News, November 22, 1938.

[170] "Democracies Uniting to Solve the Problem of Fleeing

Jews," Newsweek, November 28, 1938, 13-14, quoted in Zalampas,

166.

[172] Oswald G. Villard, "Issues and Men," The Nation,

November 26, 1938, 567; "Refugees and Economics," The Nation,

December 10, 1938, 609-610; "An Embargo on German Goods," The New

Republic, November 30, 1938, 83-84, quoted in Zalampas, 168.

[173] "Singular Attitude," Time, November 28, 1938,

10-11, quoted in Zalampas, 166.

[174] The Daily Californian, January 31, 1939.

[175] The Daily Californian, January 31, 1939.

[176] The Daily Californian, March 16, 1939.

[177] Yale Daily News, March 3, 1939.

[178] California Daily Bruin, March 1, 1939.

[179] Yale Daily News, January 20, 1939.

[180] The Daily Californian, March 3, 1939.

[181] California Daily Bruin, April 3, 1939.

[182] The Daily Californian, August 28, 1939.

[183] California Daily Bruin, May 4, 1938.

[184] The Harvard Crimson, May 6, 1939.

[185] The Daily Californian, September 8, 1939.

[186] The Daily Californian, September 27, 1939.

[187] The Daily Californian, February 2, 1939.

[188] The Harvard Crimson, September 23, 1939.

[194] Day, 2. See also Work, 206.

[199] Such polls cited in this study were taken at Yale University,

UCLA, and the University of Texas (as reported by Berkeley's newspaper).

[200] Day, 223. See also McDaniel, 50.

|