"Munich," about the hunt for the

murderers of Israeli Olympians, is a call for peace (back

to top)

By Kenneth Turan, Times Staff Writer

"Munich" is no small thing. No film by Steven Spielberg ever

is, but even for this avatar of Hollywood filmmaking this is something

apart, the most questioning, provocative film he's ever made.

A director who once proclaimed "I dream for a living," Spielberg

has literally thrown himself into the murkiest, most divisive of real-world

conflicts. Though he's never yearned for controversy, he's sure to antagonize

elements of his audience, especially those who lionized him for his treatment

of the Holocaust in "Schindler's List." Aided and abetted by

screenwriters Tony Kushner and Eric Roth, he's made a film that demands

to be seen as much for its place in the world as for whether it succeeds.

Yet for all its focus on the unrelenting blood lust between Israelis and

Palestinians, on the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Munich

Olympics and on Israel's relentless determination that "the world

must see that killing Jews is an expensive proposition," there is

a level on which this film is not about these longtime antagonists at

all.

Rather "Munich," in an unlikely way echoing David Cronenberg's

"A History of Violence," is about the soul-destroying pervasiveness

of killing and carnage and what that means for both individuals and nations.

It is a film that nominally presents justifiable homicides but then refuses

to allow us to enjoy them, that wants us to recognize that killing that

starts out in righteousness can end up in madness. A film that is finally

a desperate plea for peace.

It is that sense of a broader purpose that has caused the filmmakers

not to care that the underlying source material, a 1984 book called "Vengeance"

by George Jonas, was based on testimony by a reputed former Israeli intelligence

agent who's been discredited in some circles. Nor are they troubled that

the book was filmed before, as a 1986 HBO movie called "Sword of

Gideon." By beginning with the words "inspired by real events,"

"Munich" is letting us know that it's worried less about specifics

than about the sentiments it is eager to convey.

It is that desperation, that palpable sense of urgency about the need

for that message right now, that is simultaneously a strength of "Munich"

and a source of drawbacks. For though this is a film that almost yearns

for greatness, strains to reach it just over the horizon, it has not quite

gotten there. "Munich" is an important piece of work, easily

one of the year's noteworthy achievements, but it impresses us rather

than sweeps us away, an instance where significance overshadows filmmaking.

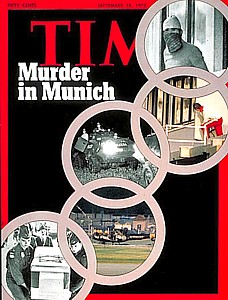

"Munich" begins with the 1972 Munich attack against the Israeli

Olympic team by Black September terrorists (subject as well of the exceptional

Oscar-winning documentary "One Day in September"). Though the

massacre is the raison d'être for what happens next, it isn't shown

in full all at once. The attack was apparently an intense experience to

film (Spielberg, who used Israeli and Palestinian actors, notes, "They

took it very much to heart, it was a very emotional catharsis ... a rugged

couple of weeks.") and the director plays out the sequence throughout

the film, parceling out the emotion bit by bit and using the memory of

the horror to motivate the team called into being to avenge it.

For at the highest levels of the Israeli government, the idea of "Jews

dead in Germany" one more time is too much to bear. Prime Minister

Golda Meir (an impeccable Lynn Cohen) authorizes the formation of a unit

of the Mossad, Israel's intelligence service, to find and assassinate

those responsible for Munich. "Every civilization," she says

in one of the film's touchstone lines, "finds it necessary to negotiate

compromises with its own values."

A young Mossad agent named Avner (Australian Eric Bana) thinks none of

this has anything to do with him. "I have," he tells his pregnant

wife, Daphna (Ayelet Zurer of the lauded Israeli film "Nina's Tragedies")

"the world's most boring job."

But, with the shadowy Ephraim (fellow Aussie Geoffrey Rush) serving as

his case officer, Avner gets picked to head the retaliation squad. He's

told that cost is no object, that he needs to minimize civilian deaths

and that his assignment of assassinating terrorists officially doesn't

exist.

Avner's team gathers in Europe, and it's appropriately multicultural.

South African-born Steve (Daniel Craig, the new James Bond) is the driver,

Belgian toymaker Robert (French actor/director Mathieu Kassovitz) is the

explosives expert, German antique dealer Hans (Hanns Zischler) is the

document forger and Carl (Ciaran Hinds) cleans the area of potential evidence

after the operations.

Though Avner lacks assassination experience, as played by Bana (known

in the U.S. for "The Hulk" and "Troy" but at his best

in the Australian "Chopper") he has the strength of personality

to lead. Convincingly Israeli, the actor projects a combination of sensitivity

and ruthlessness and he knows how to present a face for which worry is

a new experience.

A key source of information for the team turns out to be a French family

operation, father Papa (Michael Lonsdale, with 50 years of movie experience)

and son Louis (Mathieu Amalric, the alter ego of French director Arnaud

Desplechin). The family, Louis insists, is "ideologically promiscuous,"

selling information to everyone except governments, so subterfuge on Avner's

part becomes essential.

The central action of "Munich" is the assassinations the team

pulls off, a series of impressive set-pieces that showcase the Israelis'

determination to be the hammer of God and Spielberg's facility as an orchestrator

of action and tension.

The hits, however are not a series of unbroken triumphs. As always in

movies, things go wrong, egos and loyalties conflict, betrayals take place.

Even when the hits are successful, the film pointedly doesn't allow us

or the team to luxuriate in the beauty of complex, well-executed maneuvers.

For hanging over the Israelis' actions is the constant question of whether

they are doing the right thing, whether any of their targets actually

had a hand in Munich and whether they should care about those questions.

The process of taking lives, of living completely without rules in a violent,

uncertain world begins to slowly rob them of their sanity. Is an eye really

worth an eye? Is one of the team right when he says, "We can't afford

to be that decent anymore," or is Robert to be agreed with when he

wails, "We're supposed to be righteous. That's my soul. If I lose

that, I lose everything."

If this push-pull aspect of "Munich" comes off as planned,

others do not. Spielberg bolted into this film immediately after completing

"War of the Worlds" barely six months ago, a situation duplicating

his "Jurassic Park"/"Schindler's List" experience

of 1994. "Schindler" did not feel rushed, but "Munich"

frankly does.

The press notes say that this is the first film Spielberg did not storyboard.

On the one hand, he is obviously gifted enough to make that kind of off-the-cuff

moviemaking compelling, and the resulting almost docudrama feeling, aided

by cinematographer Janusz Kaminski's intentionally desaturated color,

helps us get caught up in the story. But there is also an unavoidable

feeling of hurry and lack of polish about the film, a sense that some

of the plot elements fall too easily into the generic.

"Munich's" dialogue similarly cuts both ways. Without reading

the various writers' drafts, it is notoriously difficult to tell who wrote

what in a given film, but the language here feels at once bracingly distinctive

and a bit awkward, as if it was written on the fly by some very gifted

people.

That said, "Munich" has some wonderful spoken stretches (Kushner

is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of "Angels in America";

Roth, an Oscar winner, is one of Hollywood's most respected voices), especially

about the intractable nature of the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. Ali,

a Palestinian zealot who does not know Avner's identity, tells him, "We

can wait forever. You don't know what it is not to have a home. Home is

everything." On the other side, Avener's mother tells him, "We

had to take it because no one would ever give it to us. A place to be

a Jew among Jews. We have a place on Earth at last, whatever it takes."

The intentional parallels the film makes between these two presentations,

the conflating not of actions, morals and strategies but of hopes and

dreams, joined with Spielberg's intention that the film be seen as "a

prayer for peace," is one of the things "Munich" cares

the most about. But it has led to a pre-release rush to judgment against

"Munich" from the kinds of deep-thinking columnists and fulminators

who usually find film beneath their notice but can be currently found

falling all over each other to weigh in on the subject.

No, no, no, these people are insisting, the quagmire in the Middle East

is much too complicated for a simple filmmaker to understand. But seeing

"Munich" makes one wonder if this film understands the situation

in a way those people do not. Is it possible there are fewer things worth

killing for than advocates eager to send others to their deaths confidently

assume? Why is war always deemed the realistic response to a situation;

why is peace considered the province of innocents?

In this age of feckless and unapologetic zealotry, with leaders whose

passion for extremism has led to the lamentable results we see all around

us, "Munich's" even-handed cry for peace is not an act of equivocation

but one of bravery. What "Munich" has to say, and its ability

to say it to the widest possible audience, couldn't be more needed than

it is right now. |