|

I

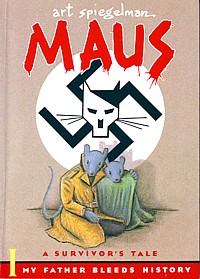

Maus is the story of two survivors of the Holocaust.

The first is Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew who, along with his wife

Anja, survived Auschwitz and came to live in Queens, New York. There,

Vladek and Anja raised their second son, Art, their post-Holocaust child

(their first son died during the early stages of the Final Solution).

Art grew into adulthood under the shadows of his parents' past, the darkest

appearing in 1968 when Anja committed suicide. Art himself is the second

survivor, although at first his torment seems self-indulgent compared

to the elemental horror of his parents' experience.

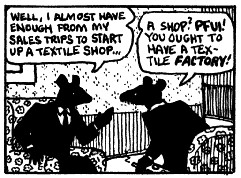

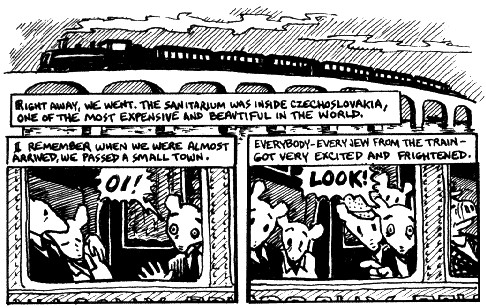

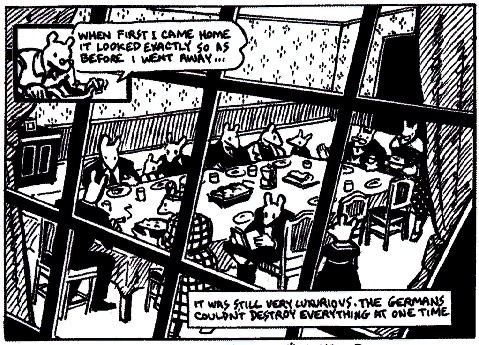

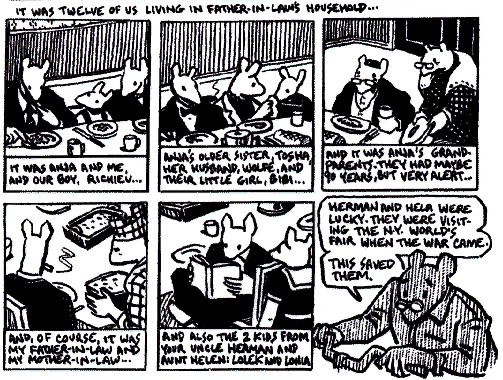

The accounts of these two survivors run through Maus as Art records his

father's memories in a series of oral interviews: Vladek's courtship of

the wealthy Anja, the marriage that facilitated his rise in the business

world of the secularized Jewish community of Sosnowiec, his induction

into the Polish Army and capture by the Nazis in 1939, his release and

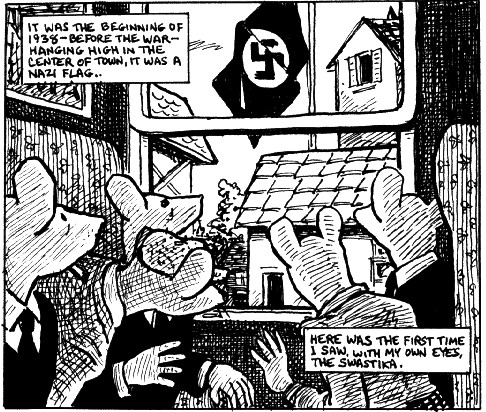

return to the area of Poland "annexed" by the Reich. Vladek

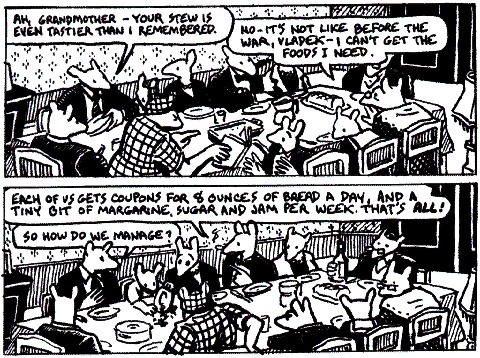

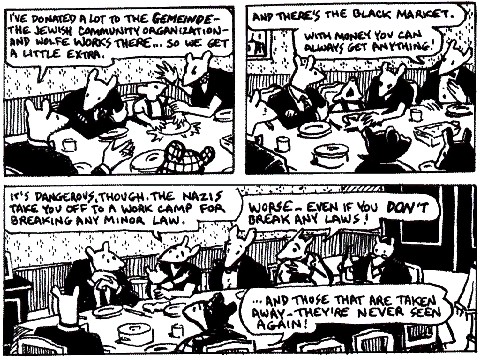

relates the steady tightening of the Nazi noose around the Jews as the

policies of extermination were put into practice, detailing how, as the

concentration camps filled, he and Anja managed to survive through cunning

strategies and blind luck, until they were caught and sent to Auschwitz.

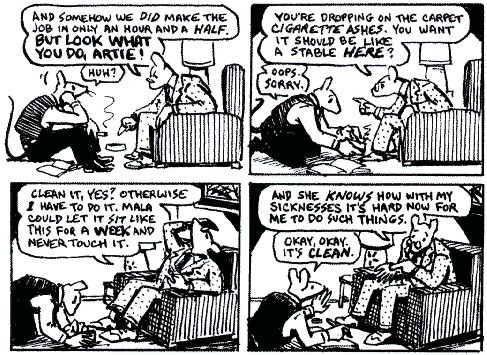

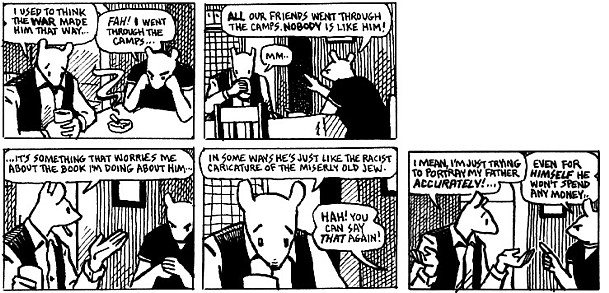

Throughout Maus, Vladek's story is paralleled by Art's attempts to come

to terms with the opinionated, tight-fisted, and self-involved father

whose personality was formed in a world and through an experience so completely

divorced from his own. The ghosts of this past swirl around Art who is

haunted by the irretrievable experiences of the dead, their residue found

in familial relationships characterized by guilt and manipulation. The

first volume closes with dual betrayals: Vladek describes how he paid

two Poles to smuggle Anja and him to Hungary only to be turned over to

the Nazis; minutes later he reveals to his son that, after Anja's suicide,

he destroyed her diaries, her account of the Holocaust for which Art has

been frantically searching.

It is logical to approach the book first as a work of oral history, because

of its sources and Spiegelman's decisions about the structure of its text.

The absence of footnotes or bibliography should not be mistaken for indifference

to the importance of research. "Essentially, the root source of the

whole thing is my father's conversations with me," Spiegelman explained

when I asked him about the sources he consulted. "Sixty percent of

those are on tape and the rest of it's during phone conversations or while

I was at his house without a tape recorder, taking notes. Now, my father's

not necessarily a reliable witness and I never presumed that he was. So,

as far as I could corroborate anything he said, I did--which meant, on

occasion, talking to friends and to relatives and also doing as much reading

as I could."

Although Maus focuses on the particularity of Vladek's story,

Spiegelman succeeds, through succinct narration and dialogue, in keeping

us aware of the changing social and political climate of Sosnowiec, and

from there the context of Poland and the Third Reich. "This is a

bottomless pit of reading if one falls into the area," Spiegelman

said. "There's building after building of books and documents. I

don't pretend to [have read them all]. On the other hand . . . I read

as many survivors' accounts as I could get hold of that touched on the

specific geographical locations [depicted in the book]." In his effort

to place Vladek on the particular map of Sosnowiec, Spiegelman was also

aided by a Polish pamphlet published after the war that chronicled the

fate of the Jews of that city. "Every region had its own booklet

... [The Sosnowiec pamphlet] was really important for the things that

take place in the last half of the first volume because it has very, very

specific information."

Spiegelman's sources are relevant, but oral history is more than a verbatim

transcript propped up by corroborative facts and context. The structuring

of an account--how a recorder shapes his or her sources, how he or she

organizes the materials into an interpretive narrative--are equally a

concern. In his choices and the critical considerations behind those choices,

Spiegelman worked as a skilled oral historian. He presented his father's

story as a chronologically-linked chain of events, restructuring Vladek's

testimony to strengthen the clarity of the account. But, the way one chooses

to tell a story is a kind of censorship, and Spiegelman conscientiously

had to weigh the impact of one narrative decision over the effects of

others:

This is my father's tale. I've tried to change as little as possible.

But it's almost impossible not to [change it] because as soon as you

apply any kind of structure to material, you're in trouble--as probably

every historian learns from History 101 or whatever. Shaping means [that]

things that came out [in an interview] as shotgun facts about events

that happened in 1939, facts about things that happened in 1945, they

all have to be organized. As a result, this tends to make my father

seem more organized than he was For a while I thought maybe I should

do the book in a more Joycean way. Then I realized that, ultimately,

that was a literary fabrication just as much as using a more nineteenth

century approach to telling a story, and that it would actually get

more in the way of getting things across than a more linear approach.

Or, as Spiegelman shows more concisely in Maus:

|