June

17, 1953 Uprising (back to top)

What

happened? Responding to pressure to work faster, construction workers

in East Berlin marched to government officials to demand a repeal of the

new norms. Disappointed with the response, they called for a general strike

across the country. Soviet forces were deployed to force strikers off

the streets. Timeline: What

happened? Responding to pressure to work faster, construction workers

in East Berlin marched to government officials to demand a repeal of the

new norms. Disappointed with the response, they called for a general strike

across the country. Soviet forces were deployed to force strikers off

the streets. Timeline:

- Apr. 1946: SPD and KPD "merge" into one

party, the SED

- Otto Grotewohl of the SPD, who had been in the USPD during WWI

and then returned to the reformist SPD, brings his party into the

union. He was arrested several times during the Nazi period but

remained in

Germany. Germany.

- Walter Ulbricht of the KPD, who had emigrated to France and then

the Soviet Union in 1938, led his party. He was very loyal to Stalin.

- 1948: the SED is "Stalinized:" discussion

and dissent are not tolerated

- July 1952: 2nd SED party conference [according to

Klessmann 1988, 263]:

- "building of socialism" is decreed, forced collectivization

of factories and farms is the method

- as a consequence emigration from East Germany increases:

Jan. 1952: 7,200 refugees registered in the West (240/day);

Mar. 1953: 58,600 registered (1950/day)

Jan.-June 1953 estimate: 225,000-426,000 refugees [Fulbrook, Anatomy

1995, 180]

- March 5, 1953: Stalin dies

- jockeying for power in Moscow:

Beria ("New Course") might have ousted Ulbricht

Semyonov gains upper hand in early June, pursues "softer course"

- June 1953:

East

German gov't raises work norms by 10% East

German gov't raises work norms by 10%

- Differing assessments are published in newspapers (Tribüne,

Neues Deutschland)

- For details, see Fulbrook 1992, 190f; or 2003 ed., 154f (on amazon,

search keyword Zaisser to read on-line)

- Malenkov summons Ulbricht and Grotewohl to Moscow, warns them

to correct the situation in East Germany by halting collectivization

and fostering independent businesses

- Announced by SU on June 9; rumors of Ulbrichts demise circulate,

expectation of repeal of work norm increase set to go into effect

- June 16, 1953: workers on the Stalinallee project

march to FDGB Union headquarters, then to the gov't House of Ministries,

demand repeal of norm increase. One "enterprising worker"

grabbed a megaphone and called for a general strike the next day. (role

of peOple/lEadership)

- June 17, 1953: 300,000-375,000 workers in most industrial

cities and towns strike or demonstrate, about 100,000 of them in East

Berlin (nationwide 5-7-10% of the total workforce, depending on whose

estimate you believe)

- Soviet tanks come out to clear the streets. About 125-250-500

people were killed and 1200 arrested

- Aug. 4, 1953: West German parliament passes a law

declaring June 17 a national holiday, The "Day of German Unity"

(although the strikes had nothing to do with a desire to unite with

West Germany).

Why did Ulbricht remain in power after 1953, when Khrushchev repudiated

the course that Stalin had set (and which Ulbricht wanted to continue

in East Germany)?

- at first Beria was ousted by Malenkow and Khruschev

- after the 1956 uprising in Hungary, SU wanted someone who could guarantee

continuity

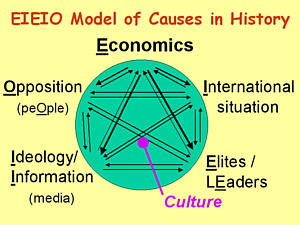

What were the causes of the 1953 uprisings?

- Economic: work norms as trigger

- Interntional politics: regime change in the Soviet

Union--new course after Stalin

- Elites: Ulbricht set the goal for the accelerated

transition to socialism

- Ideology: workers believed it was their state and

government should listen to them

- peOple: voting with their feet: going on the streets

in droves to demonstrate, also leaving East Germany

For more information, see:

|

That

is why the arrows of interaction leading out from it are darker: economics

moves other categories more directly, although all the other factors

together, combined with the luck or coincidence of natural resources

and environmental factors, determine economic developments. For so-called

primitive hunter-gatherer, nomadic and early agricultural societies,

one could substitute Environment as the heading, which

would include climate, topography and natural resources, as well as

diseases, animals and insects, etc..

That

is why the arrows of interaction leading out from it are darker: economics

moves other categories more directly, although all the other factors

together, combined with the luck or coincidence of natural resources

and environmental factors, determine economic developments. For so-called

primitive hunter-gatherer, nomadic and early agricultural societies,

one could substitute Environment as the heading, which

would include climate, topography and natural resources, as well as

diseases, animals and insects, etc.. What

happened? Responding to pressure to work faster, construction workers

in East Berlin marched to government officials to demand a repeal of the

new norms. Disappointed with the response, they called for a general strike

across the country. Soviet forces were deployed to force strikers off

the streets. Timeline:

What

happened? Responding to pressure to work faster, construction workers

in East Berlin marched to government officials to demand a repeal of the

new norms. Disappointed with the response, they called for a general strike

across the country. Soviet forces were deployed to force strikers off

the streets. Timeline: Germany.

Germany.

East

German gov't raises work norms by 10%

East

German gov't raises work norms by 10%