Prof. Mahlendorf's memoir, Introduction

(2 pages)

Introduction: Today in California

Writing now, in Santa Barbara, California,  I can hardly

believe that the events and experiences of 1933 to 1950--my formative years

and tragic, criminal years for my native country, Germany--took place over sixty

years ago, so vividly do they rise up in my mind. At sixteen, I was already

aware that my familyís history and my experiences needed recording. But it took

the long years since then to muster the courage to write them down. Not that

I feared running into feelings or remembering traumatic experiences that might

surprise me. I had been in psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy for years

and did not think that my mind held surprises for me! Rather, I was afraid to

understand who I would have become had the Nazi regime lasted.

I can hardly

believe that the events and experiences of 1933 to 1950--my formative years

and tragic, criminal years for my native country, Germany--took place over sixty

years ago, so vividly do they rise up in my mind. At sixteen, I was already

aware that my familyís history and my experiences needed recording. But it took

the long years since then to muster the courage to write them down. Not that

I feared running into feelings or remembering traumatic experiences that might

surprise me. I had been in psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy for years

and did not think that my mind held surprises for me! Rather, I was afraid to

understand who I would have become had the Nazi regime lasted.

I always knew that I participated in Hitler Youth with

greater enthusiasm than my girl friends and my classmates in grade school. I

now understand the reasons for it: Before he died in 1935, my father had become

a member of the SS. After Fatherís death, Hitler gradually became an idealized

substitute father for me. I championed his cause all the more, as my mother

showed her disapproval of my real father and of Hitlerís party. In writing this

account, I discovered, to my relief and surprise, that by the time I was thirteen

or fourteen I had begun a rebellion against the conformity Hitler Youth (HY)

demanded of us even though I was unaware of what I was doing or feeling

I took part in Jungmädchen from age ten to fourteen

like all children in Germany , attended a year-long leadership training and

went to a Nazi Teacher Seminary for a few months after graduation from grammar

school. As a member of the cohort of Germans who spent their entire childhood

under the Nazis and who became politically aware of the damage done by Nazism,

I felt that I had a special obligation to speak to my students about what we

participated in and what happened to us. I had to tell them about the enthusiasms

and the beliefs I held then; the disillusionment, anger, grief, and remorse

I experienced after German defeat; and the grief, guilt and shame that haunt

me still. During my forty years of university teaching, I taught my students

about the Nazi years and their impact on us. I read and analyzed with them literary

works on how German writers account for the Nazi past, as we called these studies

during the 1960s and 70s, and the Holocaust in German literature as we called

them since the 1980s when Holocaust Studies came in vogue. I researched German

literary texts for the relationship between individual conscious and unconscious

psychology and political ideology and power, traced vestiges of everyday fascism

in the contemporary world, and investigated the historical roots of Nazism in

educational institutions and abusive child raising practices. I wrote on the

psychology of Nazi women informers and about how German writers dealt with and

continue to deal with their Nazi past. From the late 1970s on, Feminism provided

me with a language to understand issues of class and gender and made me conscious

of the gender and class imprints on my body and my early life. Feminism also

confirmed what I knew intimately from personal experience: the personal is the

political. When I came to write the present account I did not need to consult

histories of the pre-war or post-War II periods. Both my teaching and my research

gave me the factual frame into which I could easily place my own experience,

all the more so since from about age eight or nine, I was personally and keenly

aware of such political events as Crystal Night or the German army marching

into Austria.

I began to think seriously about writing this account after

the death by breast cancer of a student of mine who fully understood and promised

to carry on my work on the socio-politics of traumatic experience and its depth

psychology. After her death, my research on the political and cultural consequences

of child abuse in German speaking countries bogged down. As a diversion from

this complex and arduous undertaking, I wrote a few episodes of my early life

and it seemed as if I had opened a floodgate. After that, it was easy to let

the memories come and to record them. The mourning for one friend led me express

my grief for childhood family and friends.

A word about my writing: Having been a refugee, having been

expelled from my hometown at sixteen without any possessions, having immigrated

as a university student to the US with only a suitcase, I have no records of

my early life, no pictures and no diaries or letters, until my late twenties.

As memories of my early childhood came crowding in --first events, and then

ever more details, particularly details about the places of my childhood-- I

found I could reconstruct the floor plan of the house I lived in to age four,

down to the staircases and hallways that I dreaded. I could visualize the streets

of the town where I walked on my way to nursery school. I could draw maps of

sections of the town we lived in till I was sixteen, including the houses, churches

and public buildings before and after their destruction during the last days

of WWII. My mind held an entire geography of childhood and, to my surprise,

my grieving turned into its celebration.

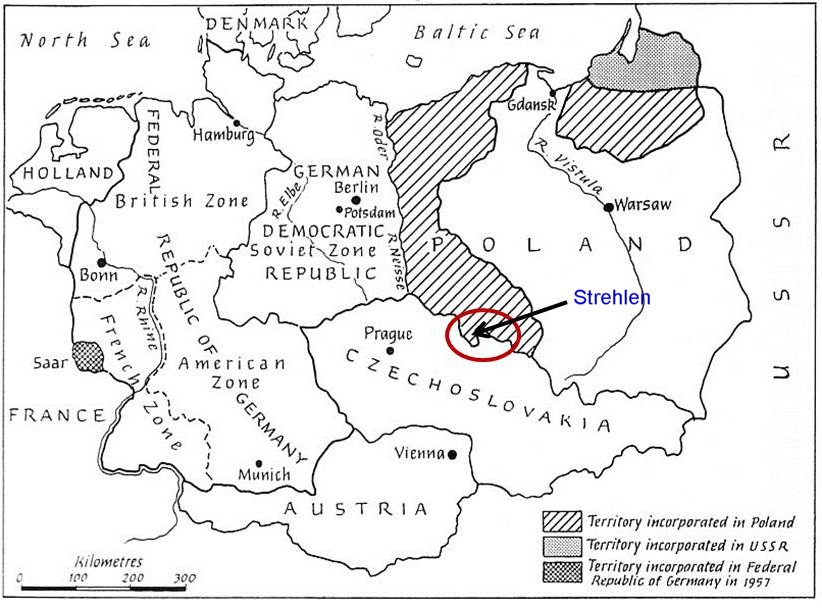

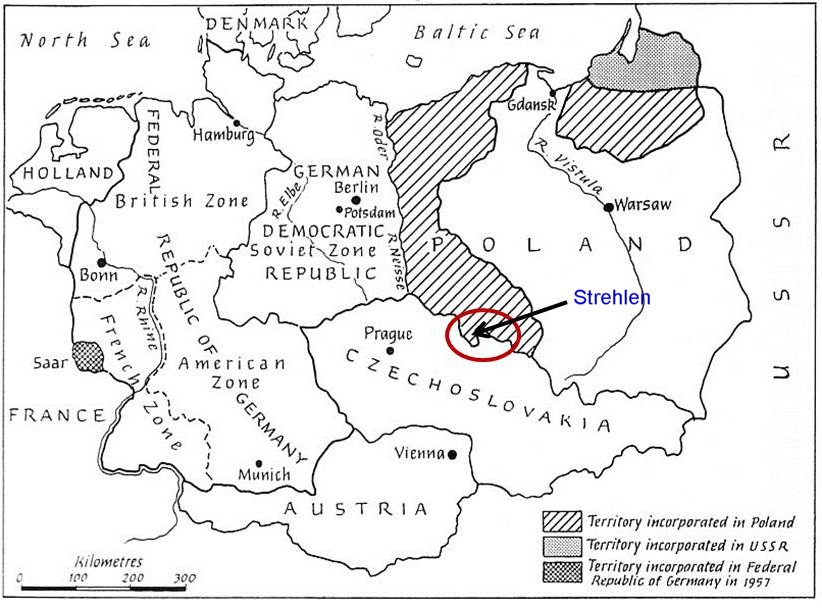

I will add my sketches and outlines of that geography instead

of the few pictures that others, like my brothers, have of the persons and places

I grew up with. Since I have no pictures of myself except for two identity card

pictures at age twelve and sixteen nor of those in my family who were meaningful

to me, I will include photographs of sculptures, some drawings and maps through

which I later attempted to understand myself and my childhood world. I did not

want to quote historical records of the time or attempt to reconstruct what

I lived with the help of maps, books, records of others. With a few exceptions,

I will not report what others told me about myself as a child but rather what

I remember about it. Therefore, my account will be strictly from my perspective,

my experience as I construct it from my memory.

The end of World War II, the Nuremberg Trials, and early

encounters with several political concentration camp survivors provided me with

enough intellectual insight into the crimes of Nazism and German militarism

to reject both by the end of 1946. An intellectual rejection is easy, as I was

to learn. During my entire life, and sometimes at the most trivial occasions,

I discovered attitudes, unconscious biases, and emotional reactions that dated

back to my Hitler Youth years. These attitudes had led a subterranean life despite

my rejection of a racist ideology and my belief in democratic forms of governance,

despite my commitment to internationalism and the UN, my social activism on

behalf progressive causes and my research and teaching of literature on the

Holocaust, on Feminism, and on the efforts of German post WWII writers to account

for Nazism.

From my first full encounter with the extent of Nazi crimes

revealed during the Nuremberg trials, I had some understanding that I had been

given the kind of indoctrination and training that could have enabled me to

participate in the persecution of the enemies of Nazism. I certainly possessed

the youthful enthusiasm and sustained some of the psychological traumatization

that can be exploited by unscrupulous leaders. And I was angry, frightened and

confused enough to have welcomed emotional release through violence. I was too

young during the Nazi period to have participated in their crimes. But by the

end of the war, in April 1945, I did come fearfully close to being involved

in one of these crimes as a by-stander.

As painful and traumatic as the loss of the war was for

me, both disillusionment and remorse led me to question myself and to reflect

on my actions and convictions. My early experience also inspired my desire to

communicate what I learned about Nazism, the Holocaust, and war and violence.

That is why as an adult I saw it as one of my tasks in teaching and public lectures

to speak about my experience so as to make my students and young people understand

how seductive any ideology, nationalism and militarism can be Ėnot just Nazism--

and where they can lead you. I pursue the account of my experience and my quest

for an education through the 1950s, when I found at the university an intellectual

haven that made my further development possible. I end it with my immigration

and my finding a new home in the United States. As I tell of the events and

persons of my early life, I will comment on how I came to see and understand

them later in my life. I believe that my experience has particular relevance

for the world of 2005 as now, again, countries everywhere embark on ideological,

military and ethnic cleansing adventures like the ones that led my country of

origin along such a destructive course.

this page may not be reproduced in any form

back to top; to UCSB Hist 133c homepage;

Hist 133q homepage

I can hardly

believe that the events and experiences of 1933 to 1950--my formative years

and tragic, criminal years for my native country, Germany--took place over sixty

years ago, so vividly do they rise up in my mind. At sixteen, I was already

aware that my familyís history and my experiences needed recording. But it took

the long years since then to muster the courage to write them down. Not that

I feared running into feelings or remembering traumatic experiences that might

surprise me. I had been in psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy for years

and did not think that my mind held surprises for me! Rather, I was afraid to

understand who I would have become had the Nazi regime lasted.

I can hardly

believe that the events and experiences of 1933 to 1950--my formative years

and tragic, criminal years for my native country, Germany--took place over sixty

years ago, so vividly do they rise up in my mind. At sixteen, I was already

aware that my familyís history and my experiences needed recording. But it took

the long years since then to muster the courage to write them down. Not that

I feared running into feelings or remembering traumatic experiences that might

surprise me. I had been in psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy for years

and did not think that my mind held surprises for me! Rather, I was afraid to

understand who I would have become had the Nazi regime lasted.