About the author:

I am a senior history major and women's studies minor here at UCSB. When

doing research, either for a presentation or a paper, I have tried to

combine my interests of history and what roles women have played in shaping

history. Prior to this class, I had some knowledge on German history.

I took History 33D with the same professor in the fall of 2002, I have

visited Berlin and Munich and have seen the sights as a tourist, and I

am an addict of the History Channel. I chose to write about the unification

of Germany because it is a recent event in history, I was alive when this

happened (although I was young child at the time) and we can still see

the effects of the fall of the Berlin Wall today.

Abstract: Abstract:

Daphne Berdahl's book Where the World Ended: Re-Unification and Identity

in the German Borderland is an ethnographic study of how the fall

of the Berlin Wall in 1989 affected the peoples of Kella, a formally Eastern

German village, on multiple levels. Berdahl explored how the Wende mutated

the borderlands of Kella, culturally, politically, religiously, and economically

during the early 1990s. Her hypothesis is that the people of Kella would

question their sense of identity/personhood with the removal of a significant

reference point (the wall). I used her book first, to see how the Wende

affected Kella's economy, which went from a bartering system in the second

economy to a more Western economic system; second to see how Kellans changed

their consumption methods, and lastly to see how Eastern and Western societal

norms were accepted or rejected. For the most part, I was able to use

her book successfully, with regards to answering my thesis, yet she was

not entirely clear on how women transitioned between mimicking Western

German ideals of gender constructs and creating their own Eastern gender

constructs. To remedy this, she could have brought together a panel of

Kellan women and asked specific questions that would have illuminated

that transition.

Essay Redefining Kellaís Heimat

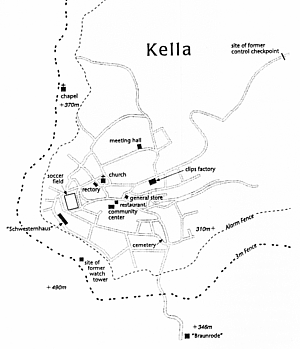

Kella

is a small village inhabited by approximately six hundred people; it is

located in north-central Germany, on the boundary of Hesse and Thuringia.

The village was divided, and partially surrounded by, the East German

border until 1989. Daphne Berdahl, the author of Where the World Ended:

Re-Unification and Identity in the German Borderland, resided there

from 1990 to 1992 and wrote an ethnographic study about the economic,

political, and social/cultural changes within the village. Berdahl utilized

interviews of villagers and town records to get a feel of what it was

like in Kella during the construction of the barbed wire fence in the

1950s (that would later become the fortified state border) and what it

was like for Wessies and Ossies to finally meet again in 1989, after the

Wall came down. She also uses these interviews to get an understanding

of what it was like to have their concept of Heimat, literally

home or homeland, first split in two and then removed altogether. One

of Berdahlís main themes is borderland and how they shape a personís character

or identity. Her main goal in the book is to: Kella

is a small village inhabited by approximately six hundred people; it is

located in north-central Germany, on the boundary of Hesse and Thuringia.

The village was divided, and partially surrounded by, the East German

border until 1989. Daphne Berdahl, the author of Where the World Ended:

Re-Unification and Identity in the German Borderland, resided there

from 1990 to 1992 and wrote an ethnographic study about the economic,

political, and social/cultural changes within the village. Berdahl utilized

interviews of villagers and town records to get a feel of what it was

like in Kella during the construction of the barbed wire fence in the

1950s (that would later become the fortified state border) and what it

was like for Wessies and Ossies to finally meet again in 1989, after the

Wall came down. She also uses these interviews to get an understanding

of what it was like to have their concept of Heimat, literally

home or homeland, first split in two and then removed altogether. One

of Berdahlís main themes is borderland and how they shape a personís character

or identity. Her main goal in the book is to:

... illuminate how a figurative borderland, characterized by fluidity,

liminality, ambiguity, resistance, negotiation, and creativity, is dynamically

heightened, accelerated, and complicated in the literal borderland of

Kella, where specificities of both come into especially sharp relief.

(Berdahl, 9)

Daphne Berdahlís book looks at the many different views of borderland;

cultural, religious, gendered, political, and economic. Her first chapter

chronicles her arrival to Kella in December 1990. This chapter is designed

to give readers a general history and outline of the village. The author

wants to show how the village transitions in the six years of her observations.

The second chapter deals with everyday life under socialism, and

how Kellans began to get a feel for their new ideals, with regards to

politics, the economy and potentially different gender norms. Here she

also looks at the power struggles between the classes and the relationships

between the state and its citizens. Chapter three is about religious

identities and resistance to socialist reforms of Catholicism. Berdahl

looks at the change between popular faith and institutionalized religion

since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Chapter four deals with the

new inequalities after capitalism is "introduced" into Kellan

society and how they deal with new types of consumption. She argues that

when capitalism is introduced the new village elites seize social capital

and transform the meanings and the principles of the consumer market economy.

The author states that chapter five is her core chapter in this

book. This chapter expands her borderland argument. Here she explains

the Kellan experience under socialism, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and

the border maintenance and identity invention after the 1989 Wende

(political turn). Chapter six looks at the transformed constructions

of gender before and after the Wende in Kella; mainly how Western images

of womanhood have altered ideals of women as workers and mothers under

socialism. The last chapter deals with the several different ideas

of historical memory since the fall of the Berlin Wall. By looking at

how, even though the Berlin Wall is no more, the memory of the past creates,

as she quoted from Peter Schneiderís novel The Wall Jumper, a "wall

in our heads" (pg.166).

Within Daphne Berdahlís book there is a main theme of the border, and

then the absence of a border, as a consistent and imposing presence, a

multitude of practical and philosophical concepts for Kellans and a challenge

to their societal and cultural norms. I will be arguing that the

fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 caused Kellan men and women to challenge

their previous identities, formed by the construction of the Wall, and

then forced them to construct different sets of beliefs with regards to

economics, consumerism, and the restructuring of societal norms.

During Eastern Germanyís second economy, social and cultural capital

were the most practical forms of goods. The second economy is about bartering

my goods for your goods and acquiring social status through these shared

networks of people. Women would wait in lines outside of Konsum, Kellaís

only store, and buy items that they not only needed for themselves and

their families, but mostly to barter for later. They did this because

the Berlin Wall cut off access to outside consumer goods, and they created

a barter system to try and compensate for that. Berdahl says that "the

political economy of socialism was based on a logic of centralized planning,

the aim of which was to maximize the redistributive power of the state"

(pg. 115). People, as a reaction to this planned economy, began to hoard

and to barter goods that were no longer available to East Germans. "Networks

of friendships, acquaintances, and associates were created and maintained

through gift exchanges, bribes, and barter tradeÖGifts, exchanged among

kin, friends, or acquaintances, were often used instrumentally" (Berdahl,

pg. 118). As an illustration, Berdahl describes how Kellans got their

elderly Wessi relatives to smuggle forbidden commodities across the border

and then later used those goods as needed. The Ossies forged their own

type of consumerism in the East, thus establishing a small part of their

identities.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Berdahl notes a transition in Ossi

consumerism from "consumer crazy" to "resistance consumers"

of East German goods. In 1990 Ossis were made fun of because they were

seemingly "consumer crazy" to the Wessis. A letter written to

Wessi relatives from an Ossi man in Berdahlís book talks about him and

his child driving through the border, from east to west, and marveling

at the many shops and grocery stores in nearby Wessi cities. Google marcuse

133c to find where this essay is published on the web. But this amazement

soon wore off. By the end of her stay in 1992, Berdahl encountered more

and more Ossis driving their Trabis, women wearing their Kittels (smocks--a

sign of a working woman), and buying local brand detergents instead of

Wessi brands. Kellans did this when they began to realize that they were

losing their Heimat, their discourse of identity. Many Wessis touted

that Ossis needed Nachholungsbedarf, literally to catch up with

Wessis economically, politically, and culturally.

Ossi women were strongly involved in first conforming to Western ideals,

and then resisting them. Berdahlís book is not quite clear on how Kellan

women went from embracing them and then resisting them. Perhaps it is

because many women will react differently to the same situations that

this is not clear in her book. Women under the new economy strived tolive

up to socialismís expectations as working women and as nurturers to their

families. They were part of Einwohnerversammlungen (town meetings),

church social life, working at either the toy store or the clips factory,

and being a "traditional homemaker." Many women Berdahl spoke

to said that they had a double or even triple burden on them. I think

this would be one of the reasons why many Ossi women looked, at first,

to the Wessi women for direction and influence. After the Wende many Kellan

women were the first to be laid off from their jobs and the most overlooked

when it came to official positions of the city. This was due to Wessi

ideals of what a woman was expected to be and expected to do within society.

Many women gave up their previous jobs and official positions and mainly

stayed at home. They mirrored many of the Wessi womenís actions, such

as staying at home, having children at a younger age, and becoming more

active consumers. One woman told Berdahl "I feel freer nowÖ.I can

do what I want. I can go shopping, not necessarily to buy things but to

look" (pg. 195). These womenís identities were at first shifted towards

Wessi ideals when those concepts seemed fresh and new, and perhaps "better",

and then shifted away from Wessi ideals and towards their self-created

Ossi ideals. They were not entirely based upon either Wessi or Ossi traditions,

morals, values, it was more of a combining of the two belief systems.

At the end of Berdahlís ethnographic study in 1992, and when she revisited

Kella in 1996, she observed a few new mentalities and behaviors. First,

Kellans seem to appreciate western consumer goods, but they still have

pride in their own Ossi-made goods. Second, they understand the concept

of consumerism, yet they do not seem "consumer crazy" like several

years ago. And lastly, women can, and do, help create new identities,

and maintain them, when it comes to the figurative new borderland of Germany

by actively participating in the government, Einwohnerversammlungen

(town meetings), and by establishing themselves as German consumers. Her

study of the Kellan community after the fall of the Berlin Wall has tried

to clarify the many different meanings of borderland "by examining

the creation, maintenance, transformation, and invention of different

kinds of boundaries and border zones in daily life" (Berdahl, pg.

233). I have tried to argue, and show, that the 1989 Wende caused Kellan

men and women to challenge not only their own identities, but to challenge

the images that the West is showing them politically, economically and

culturally.

Reviews

of Berdahl's book: Reviews

of Berdahl's book:

by Marion Deshmukh in: The Historian, v. 63(Fall 2000), 182f.

by Kathrin Hörschelmann in: Political Geography 19(2000),

658f.

Related books:

Elizabeth Ten Dyke, Dresden: Paradoxes of Memory in History

(London /New York: Routledge, 2001)(Studies in Anthropology

and History, v. 28), 316pp. not held by UCSB [DD901.D78 D95 2001]

|

Abstract:

Abstract:

Reviews

of Berdahl's book:

Reviews

of Berdahl's book: