Essay (back

to top)

In May 1945, as Germany began to collapse within, a new age dawned marking the end of an omnipotent Führer. In addition to the widespread poverty and immediate economic problems that needed to be dealt with, another large social dilemma loomed over the country. What was to be done with an entire population that were collectively responsible for the allowance of the extermination of over twelve million Jews, gypsies, minorities, and anyone who challenged the Nazi system? While the attitudes of Germans differed in determining the political direction the country should take, it was all too clear that Germany needed to rid the country of any symbols, policies, and persons who represented the old regime. Thus, the policy of denazification was introduced (Fulbrook, 108-111).

While this policy seemed to offer the solution to reuniting and regaining Germany’s credibility back in the world sphere, its journey to enact such legislation proved to be the greater problem. Due to the lack of strong anti-Hitler force within Germany and the Allies and Soviet Union’s power struggle in the East, the denazification process failed to hold high ranking members of society, specifically Nazi doctors, accountable for the atrocities committed in the concentration camps. International intervention turned into international domination and in the process of East vs. West the true vision of justice was obliterated, leaving thousands of the guilty without adequate punishment for the crime. Germany failed to establish a strong domestic Anti-Hitler opposition and thus denazification was implemented by the Allies and not the Germans (Fulbrook 116-123). Therefore, there was no adamant force within Germany that continued to hold members of society accountable for the genocide. It is both the Allies and Soviet Union’s fault for paralyzing the denazification process and causing it to fail.

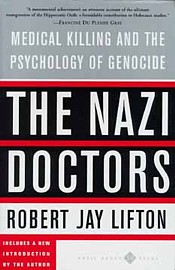

Perhaps one of the most disturbing professions to have committed inhumane atrocities is ironically enough found in the medical field. U.S. psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton investigates the role doctors have played during the Nazi regime. His published study entitled “Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide: The Nazi Doctors” explores the role that German doctors played in Nazi genocide, as well as the social implications of such behavior. Lifton’s main point is to examine the psychological characteristics and social, cultural and political factors that incline physicians to participate in genocidal behavior. While his study is mainly focused on the psychology of the Nazi doctors, Lifton offers keen insight into the political ramifications that took place as a result of such horrific behavior.

By examining the partial failure of the denazification plan and Lifton’s study on the psychology of genocide the following questions can be answered: What factors (personal, professional and political) contribute to the allowance of doctors to utilize their skills in order to cause harm rather than heal? What contributed to their lack of accountability during the post-war period? How can we be able to prevent such atrocities from happening in the future?

First it is important to address the initial question of how exactly a profession founded on the merits of healing turned drastically into a policy of direct medical killing. If it wasn’t for the “Nazi biomedical vision” aided by German doctors, Hitler would not have been able to legitimize his racist policies. Sterilization, a “forerunner of mass murder” appeared to open the floodgates that led to the genocide of WWII. Not much opposition was met by the idea since after all it was the United States that led the world into an interest in eugenics and sterilization among prisoners and those who fell into the category of “congenital feeblemindedness” (Lifton, 22-26).

In Lifton’s study he goes on to examine the blatant violation of the Hippocratic Oath and discusses this irony with his interviewees. One former Nazi doctor Fritz Klein answered “Of course I am a doctor and I want to preserve life. And out of respect for human life I would remove a gangrenous appendix from a diseased body. The Jew is the gangrenous appendix in the body of mankind” (Lifton, 16). With this roundabout way of thinking it is no wonder that scientific racism dominated Germany during the mid 1930s.

With personal and professional opposition set aside, it was no challenge to bring pseudo-science research to the forefront of German politics, since it was Hitler’s vision being carried out in the medical field.

While it is clear to see how the Nazi bio-medical vision and racial extermination began it is harder to evaluate how it properly ended and the consequences of decades of continuous death. As stated before, at the end of WWII Germany contained a demoralized population living among the wreckage of a failed empire. While it seems that international intervention might have alleviated the pressure of reconstruction off of the German people, many saw the occupation by the Allies as a “Fourth Reich” (Fulbrook, 116-117).

This assumption is not entirely inaccurate. The Allies and the Soviet Union were not only attempting to denazify Germany just on the basis of ridding the country of the previous evil regime, but also as a means to assert dominance in the East. As stated previously, the more tensions grew between the Soviet Union and the United States the more each country lost sight of what the ultimate goal was. For example, the United States and Britain used former Gestapo and SS officers for their own intelligence agencies in the East. The Soviet Union and communist regimes in Eastern Europe also similarly recruited former Nazi party members (Simpson, 78-79). It is evident that this notion of recruiting war criminals in the service of western democracies is not only a clear violation of the policy of denazification but also a blasphemy against democratic rule.

Another moral deterrence noted on the United States is the fact that doctor perpetrators were given protection in Germany. For example, in 1946 French officials called for a former SS doctor at Dachau, Kurt Ploetner, to stand trial for his Mescaline experiments on French prisoners. US intelligence reported their inability to obtain Ploetner, blaming his escape to the Soviet Union. Ploetner was never indicted and the charges were dropped in 1972. However, his experiments conveniently provided important information for the CIA and their experiments with cannabis, LSD, and mescaline in the study of mind control (Lifton, 290; Marks, 57-63).

While ultimately the Allies failed in holding these doctors responsible for their crimes that does not mean that there was no opposition. Many courageous lawyers and fellow doctors spoke out about holding those responsible. For example, Alexander Mitscherlich refutes the estimation that only 350 doctors committed medical crimes and asserts to Fulbrook that number was only “the tip of the iceberg” (Fulbrook, 43). Mitscherlich who was an official observer for the West German Chambers of Physicians at the Nuremberg doctors’ trial charged two of Germany’s top surgeons, Ferdinand Sauerbruch and Wolfgang Heubner, for participating in cruel and fatal experiments during the Nazi reign (Lifton, 457). However, Mitscherlich was sued and this information was removed from the trial records.

It is important to note that the doctors involved in medical experiments and killing were not only those employed under the Nazi regime, but also prisoners brought the camps and forced to defile their fellow prisoners. In “Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account” Dr. Miklos Nyiszli retells his close relationship with Dr. Josef Mengele, the “Angel of Death” and the horrors he committed on Auschwitz captives. This provides a dilemma on whether or not prisoners of war can be held for their actions (Nyiszli; Lifton, 358-364).

During the denazification process and the aftermath of the Nuremberg trials it became clear that compliance and suppression was the main policy for dealing with Nazi doctors. This is most likely because doctors comprised the bulk of professional participants in the Nazi party, thus approaching virtually no consequence among their professional peers.

A prime example of this is the T4 program that Lifton discusses. This program began in late 1939 and essentially worked under the façade of helping the incurable. It began with the killing of severely disabled children and soon spiraled into mass extermination under the guise of “racial hygiene.” The Nuremberg trials estimated that somewhere around 275,000 people were killed under the T4 program (Lifton, 65-72). Out of the 14 doctors charged with working in the program only one was sentenced in court after 1945. One example of the lack of responsibility held is Werner Hyde, an active commissioner of direct medical killing who helped extend participation in killing to the camps. After the war, he managed to escape persecution with the help of German doctors who covered up his previous war crimes. For 14 years he worked under a pseudonym and lived a life of luxury until he was exposed and eventually committed suicide while on trial (Lifton, 117-119).

It is apparent that the fate of Nazi doctors in the postwar period distinctly varied. Many committed suicide (some say under pressure from fellow SS members to avoid trial), and some executed under both Allied and German authority. Some escaped and a considerable number returned quietly back to their own practices. Even many are still practicing (Lifton, 458).

It is easy to see that the legacies and horrors that originated in the Third Reich will always remain prevalent in history. Not only as a means to warn of the dangers of pseudo-science and blind compliance among citizens but Nazi scientific research can still be found in the German education system. For example, at the 1986 convention for the American College of Neuropsycopharmacology a researcher used specimens from the victims of euthanasia during the 1940s (Lifton, 138). This raised many questions on the ethics of scientific research. If the crimes have already been committed is it justifiable that doctors use such specimens to conduct their own research even if originally obtained through horrific means?

Presently revelations about the morality of doctors seemed to have been transformed from denial to a state of shock and acceptance of the cruelties committed during the Third Reich. However this lesson is perhaps learned forty years too late. Justice for the victims appears to be impossible due to that fact that they themselves as well as the criminals are already deceased. However that is not to say that it is too late for the world to learn from these horrific mistakes. Inhumane experiments are still occurring in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. There is no excuse for world’s medical community to be fooled again and silent compliance is no longer acceptable.

|