| Research

Paper (back to top )

Introduction

In 2004, Ministers from the German government traveled to Namibia to

take part in the 100-year commemoration of the suppression of the Herero

uprising. It took a century for the German government to publicly acknowledge

what had happened in Germany’s Southwest African colony in the early 20th

century. The atrocities of World War II, and the German violence towards

the Jewish populations, are known throughout most of the world, yet the

German attacks on the indigenous people of Southwest Africa during their

colonial rule remain largely unknown. For years, especially after Namibians

gained independence in 1990, descendants of the Herero people pressured

the German government to apologize and give reparations for the suffering

their people experienced as a result of the Herero genocide.

For years, demands for reparations, land redistribution and reconciliation

fell on deaf ears. According to Dr. Friedrich Freddy Omo Kustaa, the German

government frequently claimed, “compensation is unnecessary because they

[Germany] already have a foreign aid package of recompense for Namibia”[1] and “apologies open up old wounds.”[2]

As recently as 2004, a Namibian newspaper quoted Ambassador of the Federal

Republic of Germany to Namibia, Wolfgang Massing as saying, “Reparations

to the Ovaherero would open up a Pandora’s box.”[3]

Nevertheless, on August 14, 2004, German Minister for Economic Cooperation

and Development Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul gave an apology for German behavior

in the colony of Southwest Africa. The problem with this apology was that

she never once said “sorry.”

The speech that Wieczorek-Zeul gave on the 100th anniversary

of the Herero uprising was definitely monumental and significant, but it

lacked real solidarity. In this paper, I focus on a critical analysis of

the speech, and try to figure out what message the Minister actually gave.

The speech itself is made up of five parts. The first section of the speech,

“Acknowledging the atrocities of 1904,” provides a brief look at the events

of those years. I have chosen a few crucial phrases from her speech to

give a more extensive and inclusive look at the atrocities of 1904 and

beyond. The following section, titled “Respect for the fight for freedom,”

makes reference to the “brave men and women…who suffered.”[4]

The section mostly continues the themes from the previous section, with

a slightly more thorough explanation of the reasons for the Herero uprising.

From the second section onward, the speech has a high level of ambiguity,

and Wieczorek-Zeul lacks clarity in most of her historical references and

promises for the future. Perhaps the most crucial part of the speech is

the “Plea to forgive.” This portion of the speech is often referred to

as the apology, although no explicit confession can be seen. I focus extensively

on this section, unpacking the Minister’s words and looking into the dual

meanings of some of her statements. Following this segment, I address the

“Shared Vision of Freedom and Justice” section of the speech. In terms

of “freedom and justice” I focus on the Hereros’ fight for these during

the colonial period, with emphasis placed on the 1904 period, and the reaction

that Germany had to these battles. The Minister ended her speech with a

section about Germany’s “Commitment to Support and Assist.” As with the

previous four sections, I critically assess the statements made, specifically

in regard to the relationship between current day Namibia and Germany.

Before analyzing the speech, this paper puts the apology into a historical

context. In order to do so, I give readers a detailed account of the German/Herero

fighting and describe how that eventually led to genocide. Further, I give

a brief look at Germany’s reaction to the genocide as it occurred in 1904.

The issue of reparations will be discussed in terms of assessing the reasons

for and against them, but I cannot delve deeper into the issue of whether

or not they are deserved, because that is a separate issue, one that I

am not qualified to answer. Instead, the main focus of the paper puts the

speech into a historical continuum in order to answer why the “apology”

came when it did, and explain the Namibian reactions that came as a result.

Last, the paper looks to discover how successful Germany has been from

2004-2008 in living up to Minister Wieczorek-Zeul’s promises of “commitment

and assistance.”

Sources

For the historical aspect of the paper, a series of books has been used

to give an overview of what happened in Southwest Africa in the years of

German colonialism. The primary books for this portion of the paper include:

Southwest Africa

1880—1894: The Establishment of German Authority in Southwest Africa by

J.H. Esterhuyse (1968), Southwest

Africa under German Rule 1894—1914 by Helmut Bley (1971) Let us Die Fighting: The Struggle

of the Herero and Nama Against German Imperialism 1884—1915

by Horst Drechsler (1981) and Namibia:

The Violent Heritage by David Soggot (1986). These books, though

older, provide a solid description of the German relations to the indigenous

people of Southwest Africa when the Germans first settled. Moreover, almost

every later book that includes a discussion of Namibia quotes these books,

so they are still the core sources. Nevertheless, I have taken great care

to make sure that I recognize what sort of biases the authors might have,

seeing as how they are all from Western cultures, not from Africa.

The majority of the other sources come from newspaper articles, online

archives, and the German Embassy website. The newspaper articles come from

two different Namibian papers, New Era and The Namibian. Articles

from these papers provide information on how the Namibian people felt about

Germany prior to 2004, and how they responded to the August speech. It

also includes editorials and opinion articles that give readers a chance

to see immediate reactions from people who were not part of the newspaper

staff. The Germany Embassy website provides demographic information on

the country of Namibia and also has some articles that address issues in

foreign relations. The script of Minister Wieczorek-Zeul’s speech comes

from the Embassy website, and is available in German and English. The text

of the German-Namibian “Special Initiative,” a document outlining the financial

aid programs that Germany participated in, serves as a crucial point of

reference for assessing post-2004 relations. Finally, several documents

written by members of the Ovaherero Genocide Association serve as examples

of how descendants of the Herero victims feel towards Germany and the reparations

issue.

Although many primary source documents exist from the colonial period,

distance and language barriers prevent me from including them in my research.

However, some documents, such as the “Extermination Order” from Gen. Lothar

von Trotha, are referenced at length in the books I used as secondary sources.

As such, I quote the well-known primary sources as I read them in translated

secondary sources.

Acquisition of Southwest Africa

On December 4, 1899, nearly a decade after Germany acquired territory

in current day Namibia, Rosa Luxemburg questioned the need for German colonies

in her piece, “Brauchen Wir Kolonien?” [Does Germany need colonies?] It

seems most likely that a main driving force for acquiring territories would

be the desire to expand trade, yet Luxemburg strongly argued against this.

Instead, she claimed that the German protectorates in Africa played “miniscule”

roles compared to Germany’s other colonies throughout the world.[5]

What then, would motivate the Germans to claim Southwest Africa, a very

arid area? Perhaps they were driven by the opportunity for military expansion,

desired more water port entries into Africa, wanted to catch up with British

expansionism, or maybe they simply wanted more land for Germans outside

of Germany. Whatever the true motivations were, Southwest Africa officially

became a colony on March 1, 1893 at the announcement of Chancellor von

Caprivi.[6]

For a colonizing power, Germany did not initially exert much effort

in the Southwest Africa territory. No “war of conquest” came about, state

involvement was minimal, and no large body of troops was sent.[7]

For these reasons, the transition of Southwest Africa into a German colony

took place in a relatively peaceful and passive way. According to Horst

Dreschler, the early period of colonization from 1884-1892 included continual

struggles between the native tribes, Herero and Nama, but not between the

tribes and the newly settled Germans.[8]

At this point, Germany had yet to gain a solid foothold in the area, and

the native tribes could carry on their normal everyday lives, including

their own internal battles between tribes.

German-African Relations Pre-1904

While the first few years of the German command over Southwest Africa

witnessed a certain amount of passivity, this began to change once more

Germans began to venture into the territory. Even before Germany came to

possess the territory, German missionaries resided in the land and developed

close relations with some of the tribes. In fact, German Lutheran missionaries

educated Hendrik Witbooi, the leader of the Nama tribe that would later

fight the Germans. As a result, the missionaries, and later the Germans

became intertwined in tribal wars and rivalries.[9]

Importantly, the native tribes in the territory exhibited clear signs of

developed civilizations. Too often Western societies falsely perceive Africa

as a “dark continent” with little development before European settlement.

According to J.H. Esterhuyse, Kamaherero, leader of the Herero tribe in

1876, asked the Cape Government (British) to, “Send someone to rule us,

and be head of our country.”[10] Without the original source this

cannot be checked, yet this author is suspicious that this sentence may

have been taken out of context, if not falsified. Regardless, since the

Nama and Herero had set areas of land on which they lived, German desires

to settle these lands would definitely cause conflicts.

Starting in 1893[11] conflict between the Herero and

Nama tribes slowly began to involve Germans as well. In 1885, German chancellor

Bismarck sent Dr. Heinrich Goering to establish peace with the natives

in the form of “protection treaties.”[12] Essentially these treaties offered

German protection to one tribe against another rival tribe. The sincerity

of these protection treaties comes into question when one looks at how

many different treaties the Germans formed with various tribes. Surely

they could not “protect” all of them in a just and righteous manner. After

some time, even the tribes became aware of the crooked nature of the German

protection treaties.

By the late 1890s, the German government had stepped up its involvement

in Southwest Africa. Dr. Goering had called upon the government to establish

a military presence to safeguard the business interests of the German

Colonial Company for South West Africa.[13] When Germany first obtained the

land it was skeptical about spending a large sum of money in the seemingly

barren land, but by 1889 the German government heeded Goering’s warning

and Bismarck sent Captain Curt von Francois to protect the land.[14]

Sending an official to govern the area signaled the interest of the German

government to protect what it considered German land. Unfortunately, von

Francois proved an ineffective leader, and he failed to stop the native

battles. Instead, the Herero and the Nama under Chief Hendrik Witbooi signed

a peace treaty that aimed to halt tribal fighting in light of the new German

threat.[15]

Captain von François not only failed to stop the battles, he launched

his own campaign against the tribes, a clear deviation from the peaceful

atmosphere that Germany sought. Naively thinking that he could easily defeat

the Nama, von Francois launched a “surprise war,”[16]

in 1894, but he faced embarrassment and defeat at the hands of Chief Witbooi,

an experienced military man. The military capabilities of the tribes should

not be underestimated; by this time modern guns had circulated[17] in the territory, which led to sophisticated

forms of fighting. In 1894, the German government, unhappy with von Francois’

behavior and upset with his inability to quash the fighting, appointed

Theodor Leutwein as his replacement.[18] From this time forward, the relations

between the Germans and the natives would take drastic steps away from

peace and towards more prolonged and violent fighting.

Treaties and Land Issues: Ownership and Dispossession

Even in an arid landscape, with little opportunity for agricultural

advancement, disputes over land dominated the relationships between the

inhabitants of Southwest Africa. Prior to the German arrival, the

Nama and the Herero had fought over land, and the coming of the Germans

added another party to the land dispute. Unjust treaties that clearly favored

the Germans over the Africans characterize the way in which Germany acquired

the territory in Southwest Africa. For example, in August 1883, just a

year before the Germans officially claimed the territory, Adolf Luderitz

struck a land deal with the Bethanie people who resided in the southern

area near the Cape Colony. In this deal, the Bethanie people agreed to

sell “20 geographical miles” of land.[19]

The deceitful nature of this trade was evidenced by the fact that the Bethanie

people did not know that a “geographical mile” was not equivalent to an

“English mile,” in fact, it is six times larger.[20] Through this kind of deceptive trading, the German

colonizers obtained large amounts of land under seemingly legal pretenses.

Ironically, the land purchased by Luderitz did not hold significant value

at that time.

Despite the fraudulent nature of the majority of the land treaties in

the 1880s, the treaties of the 1890s dealt instead with promises of protection.

As mentioned previously, the Herero and the Nama tribes continually fought

over several issues, including land ownership and cattle. Playing off of

their vulnerabilities, the Germans aimed to create protection treaties

with all the tribes in order to offer protection against other tribes.

The catch with these deals was that they put “intolerable restrictions”

on the tribes, which included limiting the right to wage war and the right

to raid cattle.[21] Without these

two rights, the power of the tribes dwindled under the rising authority

of the Germans. Most significantly, the ownership of cattle served as the

chief form of private ownership for the Herero and Nama people.[22] The issue of land and cattle ownership

would arise again after the Herero/Nama uprising in 1904.

Uprising and Genocide 1904-1907

The events of 1904 resulted from a culmination of ten years worth of

tensions between the Herero, Nama, and Germans, in addition to the longstanding

fighting between the tribes prior to German intervention. Ironically, when

Captain von Francois came to Southwest Africa in June 1889, the German

government advised against fighting with the Africans, and specifically

mentioned keeping peace with the Herero.[23] By the time Leutwein replaced von Francois in

1894, the damage had been done—fighting with the Herero and Nama had begun.

Whatever reservations the Herero and the Nama had towards the Germans were

confirmed in the unprovoked war that von Francois launched. According to

von Francois, “virtually everyone…was convinced that the Herero needed

to be taught a lesson.”[24] In order to teach this “lesson” German troops

set out for Southwest Africa, despite the initial plan of a peaceful existence

in the territory based on a small budget.

Against this backdrop, the Herero and Nama chiefs, Samuel Maherero and

Hendrik Witbooi, finally joined forces against the Germans. Previously,

the Herero had signed a protection treaty with the Germans, which allegedly

protected them from the Nama, who did not sign any treaties. As von Francois’s

violence towards the Herero continued, Witbooi instigated a peaceful negotiation

with Maherero in order to join forces, and it finally became a reality

in November 1892.[25] The union of these two chiefs might have had

a significant impact on the Germans, had things gone the way that Chief

Maherero planned. [This paper was published on a UCSB website.]

By 1904, the displacement of tribal people, combined with the German

seizure of cattle, finally led Samuel Maherero to launch an uprising against

the German colonists. Due to their partnership established at the 1892

treaty, Maherero urged Witbooi to join the uprising by sending him a famous

letter that stated,

Rather let us die together and not die

as a result of ill-treatment, imprisonment, or all the other ways…Make

haste that we may storm Windhuk—then we shall have enough ammunition. I

am furthermore not fighting alone, we are all fighting together. [26]

This portion of the letter shows how passionately Maherero felt about

fighting against what had turned into German oppression and exploitation

of his people. Unfortunately, Witbooi did not receive the letter because

Maherero’s messenger allegedly turned it over to Leutwein instead.[27]

This betrayal dealt Maherero a fateful blow. In the following months, Leutwein

could not put down the revolt, and the Germans appointed General Lothar

von Trotha to replace him and suppress the revolt.[28]

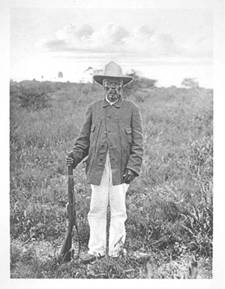

General von Trotha replaced Leutwein because of his military prestige

and his hard-line approach to war, both of which contributed to the horribly

brutal outcome of the Herero uprising. Shortly after coming to Southwest

Africa, von Trotha placed the territory under martial law on June 11, 1904,

giving him even more power.[29]

By the time von Trotha arrived and took over, the Herero had already retreated

to Waterberg after several intense battles against Leutwein’s forces.[30] At this point, von Trotha probably

could have ended the fighting quickly and efficiently, with minimal bloodshed.

Instead, he chose a path that led to what became a bloody and torturous

annihilation against the Herero people. Most famously, on October 2, 1904

von Trotha issued his “extermination note” which denied all rights to the

Herero, labeled them all as outcasts, and denied protection even to women

and children. It remains unclear whether this order came from von Trotha

himself, or whether it was passed to him from a superior official in Germany.

Regardless, what happened to the Herero people as a result cannot be ignored.

No doubt the actions of the Herero against the Germans were violent,

but nothing justified the reaction from von Trotha that led to the deaths

of thousands of Herero. By the time that von Trotha issued his extermination

order, the Herero had for the most part retreated to Waterberg, where the

Herero met their horrible fate. General von Trotha and his troops surrounded

the Herero from all sides except one; the one side they left unmanned led

the Herero people straight into the Omaheke desert.[31] In the desert, thousands of people died of starvation

and dehydration, and some of those who did reach water died of poisoning,

as the Germans had poisoned several water wells.[32]

Most likely the Herero would have surrendered rather than face their death,

but they did not have this choice. Von Trotha issued the extermination

order after the Waterberg

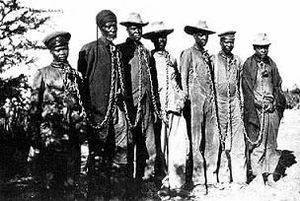

fighting in which the Germans had already clearly won. Those who did survive

faced life in prisoner of war camps such as the one located on Shark Island.[33]

In the camps, prisoners were forced into hard labor and all abuses towards

them went virtually uncontested.[34]

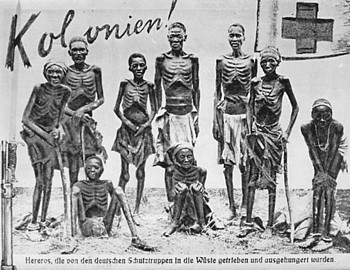

By the end of the fighting the Germans had decimated the Herero population.

Furthermore, the Nama suffered serious losses as well, including the death

of Chief Witbooi in 1905. Altogether, an estimated 80% of the Herero population

had been killed and approximately 50% of the Nama.[35] In addition to the massive loss of lives, a significant

portion of Herero and Nama cattle had been killed or seized as well.[36]

To punish the Herero and the Nama for uprising, the German colonial government

forbade them from owning land and cattle,[37]

the two main pillars of their crushed civilization. According to Helmet

Bley, at this time the Germans successfully turned Southwest Africa into

a German colony. The Germans took complete control of the area and turned

it into a tightly controlled colony. Interestingly, on November 11, 1905,

Kaiser Wilhelm II praised the Germans’ behavior in the colony stating,

“I warmly thank the troops…who defended our territories with heroic courage.”

[38] The combination of land misappropriation, property

dispossession, and serious human rights abuses formed the foundation for

the Herero people’s calls for reparations in the century that followed.

Namibian requests leading up to 2004

For years, the Herero request for reparations had gone unnoticed. At

the very least, the Herero people felt they deserved an apology for the

German atrocities in 1904. In early 2004, Arnold Tjihuiko, chairman of

the Herero Committee for memorial festivities put it simply when he stated,

“We want the Germans to say ‘we’re sorry!’”[39]

Some, like South African Professor of Law Shadrack Gutto felt that admitting

guilt did not “logically mean you have to pay…an apology acknowledges wrongdoing

even if you don’t pay a cent.”[40]

Still other felt that monetary compensations were not only deserved, they

were necessary to make up for the German brutality and the takeover of

Herero land.

In the fourteen years between Namibian independence in 1990, and the

century commemoration of the genocide, the issue of reparations was an

ever-present issue. In 2001, using the Alien Tort Claims Act, a group of

Herero brought a lawsuit demanding two billion dollars in damages against

the German Imperial Government, Deutsch Bank, and Woermann Line whom they

accused of participating in the genocide and crimes against humanity.[41] This lawsuit served as a point of contention

with the German government who refused to move forward until the Herero

Peoples’ Reparation Corporation dropped the pending lawsuit.[42]

Unfortunately, the Herero did not have the support of the Namibian government

in this demand for reparations, most likely because at this point, the

two governments enjoyed a friendly relationship, and the lawsuit would

only complicate things. As such, the demands for reparations came primarily

from the lower levels of society, not the state or national levels of government.

Despite the setbacks, several groups of people such as the Herero Peoples’

Reparation Corporation and the Ovaherero Genocide Association continued

to pressure the German and Namibian governments to act. Festus Muinjo,

a Namibian, stated, “The Herero issue will not stop, it will continue ad

infinitum.”[43] Namibians continually

pushed for “resolution, restitution, and reconciliation”[44] to make up for not only the loss

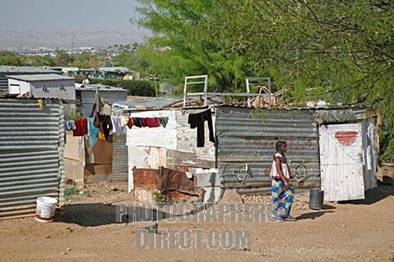

of life, but the loss of property as well. As of 2004, German descendants

owned and controlled approximately 65% of the arable commercial land in

Namibia. To put that percentage in perspective, one should realize that

only 6% of the population is white.[45] Furthermore, though Namibia has been independent

from Germany for almost 90 years, German companies make up a significant

portion of the companies operating in Namibia. Due to this unequal distribution

of agricultural and monetary wealth, it is no wonder that the Herero continually

fought for compensation.

German reasons against reparations

Naturally, the German government was not receptive to the Herero

requests for monetary compensation and land redistribution. First, the

events that the Herero requested compensation for happened 100 years ago,

making it extremely difficult to apply modern day legal arguments to the

issue. In 2004 the German Ambassador to Namibia, Wolfgang Massing, claimed

that the pending law suit "will lead nowhere … we should move forward

together and find projects to … heal the wounds."[46] Massing’s statement reflected

the larger overall argument of the German government, that reparations

would not only be implausible, the German government “simply did not see

the need for specific financial compensation.”[47]

In response to the requests for monetary compensation, the German government

denied the need for compensation based on the amount of development aid

that they have provided to Namibia over the years. In a letter to the New

Era editor published on August 19, 2004, Ambassador Massing

explicitly stated, “for the German government, the Government of Namibia

is the only partner for any negotiations with regard to development assistance.”[48] Not only did Germany take an opposition

stance against reparations, it refused to have open dialogue with anybody

except Namibian government officials, an unfortunate event for the Herero

given the government’s previous lack of support. Overall, the German government

remained adamantly opposed to repaying the Herero people. Two German political

parties, the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union,

claimed that reparations would negatively affect German citizens and cost

them billions in tax dollars.[49] Furthermore, the fact that Namibia already received

approximately US $14 million a year from Germany deterred many German officials

from wanting to give reparations to the Herero.

The “Big Change:” 2004 Apology[50]

On August 16, 2004, amidst a plethora of memorial celebrations and cultural

events commemorating the Herero and Nama ancestry, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul

gave her celebrated “apology” speech. Although there had been open dialogue

between the two governments, this speech and the presumed apology came

as quite a shock for Namibian citizens. During the speech, a member of

the crowd allegedly yelled “apology!” in order to get the Minister to actually

say the word, although whether or not Wieczorek-Zeul responded is unknown.[51] What was most shocking about the

apology was the fact that it came in the midst of the reparations debate

and the pending 2001 lawsuit. Unfortunately, as monumental as this speech

appeared, for many Herero and Nama descendants, it was not enough.

A look into the ambiguous and noncommittal nature of the speech makes

one question the sincerity of the statements made by Wieczorek-Zeul. According

to feminist writer Julia Penelope, “Language forces us to perceive the

world as man presents it to us.”[52] This quote, and other linguistic

research by Penelope in her book Speaking Freely: Unlearning

the Likes of the Father’s Tongues, allows one to critically

examine rhetoric that politicians use in speeches, documents, and other

important declarations. An in-depth analysis of rhetoric is essential to

understand Wieczorek-Zeul’s speech, especially in reference to what Penelope

calls “missing” or “passive” agents. Penelope calls these omissions, “dummy

it” meaning that the listener has to interpret what the speaker said since

the speaker suppressed important information.[53]

In the case of the apology speech, Wieczorek-Zeul frequently made passive

claims in order to admit atrocities, without concretely taking ownership

of the crimes.

Acknowledging the Atrocities of 1904

The first section of the speech began with the Minister admitting that

she was “painfully aware of the atrocities committed” by the Germans in

Southwest Africa, and she then referenced the Herero revolt and the subsequent

“war of extermination” instigated by General von Trotha.[54]

She further referenced how the survivors of the battle of Waterberg “were

forced” into the desert, and “were interned” in camps.[55] Although Wieczorek-Zeul mentioned these events,

her lack of detail and her use of the passive voice in the presentation

of events leave one somewhat in the dark about the extent of the brutality

that the Germans carried out against the natives. She made no specific

mention of the death figures of these camps, in which Germans forced over

eight thousand captives to perform harsh labor building German railway

lines.[56] Nor did she comment on

the fact that after the German parliament rescinded the extermination order,

the concentration camps continued and were not abolished until 1908[57]

The speech made no mention of the fact that the “hard labor” continued

after the uprising and after the concentration camps closed.

The frequent use of passive voice in the Minister’s speech allowed

her to admit atrocities without actually saying that Germans committed

them. By using passive voice with no “active agent” (i.e.: someone doing

the work) the sentence put the focus on the victim.[58] For example, the sentence “the

survivors were forced into the Omaheke desert” lacks a clear indication

of who forced them into the desert, and as a result, the focus is on what

happened the victims (Herero/Nama), not who inflicted this upon them (Germans).

The speech gave the perceived notion of a true acceptance of what happened

in 1904, but in reality its passive voice deceived listeners into thinking

this.

Respect for the fight for freedom

The second portion of the speech addresses the Herero and Nama people

who fought against the Germans and suggests that the Minister had great

pride in her political party for standing up for what happened to the Herero/Nama

people. Immediately after commending the Herero/Nama fighters, Wieczorek-Zeul

shifted her focus to the SPD, her own political party, and commended August

Bebel, then chairman of the party, for condemning the oppression and honoring

the fight for liberation.[59] True, Bebel did question the behavior of Germans

in Southwest Africa, yet there is a difference between questioning something,

and actively trying to stop it from continuing. Furthermore, to say that

Bebel “respected the fight for freedom” is somewhat of an exaggeration.

The SPD did oppose colonial policy, yet when

given the chance in 1904, the party did not oppose sending reinforcements

to put down the uprising.[60]

Plea to forgive

What many Namibians refer to as the “alleged apology” appeared in the

“Plea to Forgive” section of the speech. This section, the longest section

of the speech, is arguably the most important. First, the Minister started

by claiming, “the atrocities committed at that time would today be termed

genocide—and nowadays a General von Trotha would be prosecuted and convicted.”[61]

According to Article II section (a) of the Geneva Genocide Convention of

December 9, 1948, genocide is defined as, “killing members of a group”

and under section (c) “Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions

of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or

in part; committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national,

ethnical, racial or religious group.”[62]

Based on this United Nations definition, the Minister was correct in stating

that the acts in Southwest Africa were genocide. In the words of Herero

chief Clemens Kapuuo, “there is little difference between the extermination

order of General von Trotha and the extermination of the Jews by Adolf

Hitler.”[63] The question to consider is whether

or not von Trotha issued the extermination order on his own, or if the

German government endorsed and/or encouraged it. If the comparison to Hitler’s

extermination of the Jews is accurate, then one can say that the German

government, not just von Trotha, is in fact guilty. In fact, von Trotha’s

descendants visited Namibia in 2004 and gave a statement that corroborated

this, insisting that von Trotha had acted on the orders of the German state.[64]

In the second controversial statement in this portion

of the speech, Wieczorek-Zeul made reference to the Christian Lord’s Prayer,

and pleaded with the Namibians to “forgive [us] our trespasses.”[65]

Though this reference to the Lord’s Prayer makes sense considering Namibia’s

large Lutheran population, the fact that the early missionaries played

a prominent and controversial role in the early history of the period makes

this a risky statement to make. Moreover, a member of the Ovaherero Genocide

Association noted in early 2004,

Given its background, one would expect the Lutheran Church to be careful

not to be seen as a partner in Germany’s refusal to acknowledge the Ovaherero

genocide and pay reparations …the appropriate role of the church is to

provide spiritual and moral support, and not to enter into negotiations

with Germany on behalf of the Ovaherero. [66]

Finally, whether the Minister intentionally chose those words or not,

the statement “forgive us our trespasses” includes a dual meaning in reference

to moral offenses, and actual trespassing on an individual’s land, which

the Germans did extensively in the colonial period. The Herero, as a result

of German colonialism, lost their land, its natural wealth, and other forms

of properties. In addition to the sheer loss of life, this loss of property

also made up a large portion of the reason why the Herero/Nama people demand

financial compensation. It should be noted as well, that despite the arid

climate and lack of arable land, Namibia’s natural resources include: diamonds,

copper, uranium, gold, lead, tungsten, zinc, and many other minerals that

are highly valuable in today’s society. Clearly, the land that the Germans

seized from the natives has great worth. According to the German Embassy

website, Germany feels that Namibia offers a secure place for investment,

especially in the mineral sector. Yet the German government still refuses

to allow a redistribution of land to provide disadvantaged Herero with

their own land.

Shared vision of freedom and justice

The second to last section of the speech, which addresses freedom and

justice, ties in to the land issue and the plea to forgive, and makes one

wonder what “freedom and justice” the Minister actually meant to refer

to. In a bold statement, the Minister declared that Germany foresaw a “vision

that you and we share of a more just, peaceful and humane world” that “rejects

the overcoming chauvinist power politics.”[67] Still, like the previous parts

of the speech, this too lacked specificity. How could Wieczorek-Zeul claim

to “reject power politics” when her own German Ambassador Wolfgang Massing

refused to talk with any non-governmental representatives? Furthermore,

the German Embassy itself recognizes that only inhabitants of European

descent and a “new” black middle class can maintain a European standard

of living in Namibia.[68] Again,

how does this represent justice? Sadly, the damage done by the German colonial

government still has lasting effects on the natives.

Committed to support and assist

Minister Wieczorek-Zeul ended the commemoration speech by making reference

to Germany’s commitment to support and assist Namibia. However, only a

very small portion of this section even addressed Namibia. The first paragraph

outlined Germany’s achievements in becoming a “multicultural” country and

“a committed member of the United Nations.”[69]

These German achievements do virtually nothing for the Namibian people.

Rather than specifically addressing how Germany exhibits “commitment” to

Namibia, the Minister continued using highly ambiguous language. She spoke

of a “special historic responsibility towards Namibia,” and that Germany

wishes “to continue our close partnership at all levels.”[70]

The problem here lies in the fact that the Namibians, specifically the

Herero, demand “reparations and reconciliation,”[71]

which does not necessarily require a “close partnership” between the countries—it

requires monetary compensation in their eyes. In closing, the Minister

made a point to affirm Germany’s dedication to helping with Namibian “challenges

of development” and “land reform” in particular.[72] Again, one can see no solid explanation of how

Germany will undertake this task, like other statements, it appears like

an empty promise.

(continued below) |