Abstract

Since the late 1970s

Holocaust museums and education centers have emerged across the

United States. Their goals are remembering the victims of the Nazi

genocide, and educating the public so that such an atrocity will

never happen again. These museums quickly became a vehicle for both

teachers and students to learn about the Holocaust. They helped

to shape the ways that the Holocaust is taught throughout the U.S.

While teachers are now often relyi on museums to educate their students

on the Holocaust, the museums rely heavily on teachers to prepare

the students before the visit to their facility. This project examines

the education programs offered by two Holocaust museums in the United

States, the Los Angeles Museum of Tolerance and the Houston Holocaust

Museum. It evaluates their efforts in teaching middle and high school

students. Despite different approaches to learning, themes of tolerance,

personal responsibility, and personal choice are emphasized in the

education programs, often at the expense of teaching and learning

about the Holocaust itself. |

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

|

On a humid Houston morning, a yellow school

bus filled with high school students makes its way to the museum district

of the city. As they pull up to their destination point, the students

gaze out the bus window and notice how it does not look like most

museums they have seen before. A building with a black cylindrical

structure and six steel poles emerging from a slanted, wedge-shaped

edifice interests some students in what they are about to experience. A

friendly staff person meets them at the entrance to welcome them to

the Holocaust Museum Houston, and then escorts them into the building,

walking past the entrance desk and into a classroom. They know they

will be learning about the Holocaust, since their teacher discussed

the upcoming field trip, but few realize that they will learn much

more than just the history. Their emotions will be incited and they

will take away lessons beyond the history they expected to learn. For

these students, the museum will help bring the Holocaust closer to

home.

Fifteen hundred miles away, on a sunny southern

California day, a similar group of students arrives at the Museum

of Tolerance in Los Angeles. Their teacher hurries them off the bus

in order to make the scheduled arrival time. The students arrange

themselves in a single file line outside a brick building, standing

eight stories in the air, in the busy Pico Boulevard neighborhood

of Los Angeles. They enter the museum through tinted glass doors

and are told to turn off all cell phones and remove everything from

their pockets. As the security guards pass each student through metal

detectors and check all belongings, the students begin to realize

this is not like other museums they have visited. They too know why

they are at this museum—to learn about the Holocaust—but they are

also aware that the issue of tolerance will be addressed. Some students

will leave feeling empowered to take action against injustices, while

others will be incited to seek out additional knowledge. They will

remember some information about the Holocaust and will relish the

experiences of playing with the computers and other technology.

For these students, the Holocaust is just one thing they will learn

about during a full day of field trip excitement.

--------------------

The Holocaust is one of the most horrific

crimes of the twentieth century, and historians have spent much time

analyzing the causes, nature, and consequences of this gruesome event.

Over the past three decades, many institutions, like the Holocaust

Museum Houston and the Museum of Tolerance, have emerged with the

goal of trying to teach how and why over 11 million individuals, 6

million of them Jewish, could be savagely murdered. These facilities

also provide a place of solace for people remembering the lives lost. While

serving as both a place of remembrance and learning, Holocaust museums

in the United States have undertaken a complicated task in educating

both students and adults about an event that is difficult to comprehend.

As many young people learn about the Shoah from history books or popular

mainstream movies like Schindler’s List, or more recently,

The Pianist, Holocaust museums remain places that teachers

are relying upon to further their students’ knowledge.[1]

The Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles and

the Holocaust Museum Houston opened their doors in 1993 and 1996,

respectively, while interest and growing Holocaust awareness in the

United States was blossoming. As state governments began to pass

legislation in the 1990s requiring that teachers add the Holocaust

to their social studies lesson plans, instructors turned to various

outlets, including museums, for information on how to approach these

difficult issues. Museum educators planned teacher in-service trainings,

created guidebooks and teacher resources, and brought classrooms into

the museum setting. The educational mission of these museums quickly

came to include the goals of combating intolerance, prejudice, and

anti-Semitism as lessons that can be learned from studying the Holocaust.

While teachers often rely on museums to educate their students on

the Holocaust, the museums depend heavily on teachers to prepare the

students before the visit to their facility. These museums quickly

became vehicles for both teachers and students to learn about the

Holocaust, and they began to shape the ways that the Holocaust was

taught across the U.S.

In this study, I examine how the education

programs offered by two urban Holocaust museums, the Holocaust Museum

Houston and the Los Angeles Museum of Tolerance, teach middle and

high school students about the history of the Holocaust and the lessons

that can be learned. Despite different approaches to learning,

these two museums’ education programs emphasize themes of tolerance,

personal responsibility, and personal choice, in some cases at the

expense of teaching and learning about the Holocaust itself. Regardless

of scholarly criticism, I argue that one does not need to teach only

the history of the Holocaust in order for students to learn about

the event. The Holocaust Museum Houston exemplifies that a middle

ground between teaching history and promoting tolerance education

can be achieved. The Museum of Tolerance, on the other hand, also

attempts to focus on teaching history and teaching tolerance, but

unfortunately, it sacrifices crucial aspects of Holocaust history

in the process.

This thesis explores the Holocaust Museum

Houston and Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles as institutions committed

to educating youth. I begin with a discussion of each museum’s background,

goals, and other distinguishing factors that led me to choose these

institutions as case studies. Next, the literature review examines

current work in the field of Holocaust commemoration in the United

States and its implications for museums today. I also provide a short

survey of the role of museum educators and museum education in teaching

youth. The section, History in the Museum, begins by evaluating

the materials developed by museum educators for teachers to help prepare

students before a visit to the museum. I also explore the physical

space of the museums and its role in the student’s visit. Next, I

evaluate the main exhibition halls in Houston and Los Angeles and

explore how each teaches students about the history of the Shoah and

the lessons that can be learned. By examining how each museum portrays

certain events, such as the Nuremberg Laws and acts of Jewish and

non-Jewish resistance, I am able to observe the methods, successes,

and shortcomings of these institutions. The final section, Lessons

Learned, explores how the debates discussed in the literature

review, such as the notion of uniqueness, are played out in the exhibits.

I also evaluate what learning went on in the museums, by examining

letters written by students following their visit. This helps to

illuminate what students experienced and how their visit to a Holocaust

museum affected them.

When Ellen Trachtenberg and other members

of the Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Exhibit Committee met with

exhibit designers for the first time, they conveyed their three wishes

for the museum’s permanent exhibition. They wanted to discuss life

before the Holocaust, highlight the children who were savagely murdered

by the Nazi regime and its collaborators, and focus of the oral histories

provided by Holocaust survivors now living in Houston.[2]

Comprising the committee were two Holocaust survivors, constituents

of the Jewish community, and staff members of the museum. They hired

Dr. John K. Roth, a Professor of Philosophy at Claremont McKenna College

and a noted scholar in the field of Holocaust studies, to write the

text panels that would fill the museum. He recalls that two major

themes were kept in mind when they created the main exhibit:

We wanted to tell

as much of the history of the Holocaust as possible, and we wanted

to link that history to the local Houston context as much as we

could. We also felt that it was important to do more than many

museums do with the earlier history of the Jewish people.[3]

To continue this focus on personalizing

the story, they began to research locally and listen to the oral histories

of survivors. At one point, upwards of 900 survivors were living

in Houston, and provided a remarkable resource and inspiration for

the creation of this museum. Because space was limited, the exhibit

designers told the committee they should choose seven of the survivors’

stories to be highlighted throughout the exhibit hall. While this

proved to be a difficult challenge, they eventually decided on seven

stories which displayed a variety of experiences. Their stories are

carried throughout the exhibit, beginning with a family tree that

indicates those who perished in black ink and those who survived in

white ink. As the exhibition progresses, panels provide updates of

what the local survivors were facing at that time. This emphasis on

the lives of survivors who made Houston their home after the war makes

this exhibit especially unique and personal.

By March of 1996, the museum had welcomed

its first visitors and had crafted a mission statement emphasizing

its main objectives:

The mission of Holocaust Museum Houston is

to promote awareness of the dangers of prejudice, hatred, and violence

against the backdrop of the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of

millions of Jews and other innocent victims. By fostering Holocaust

remembrance, understanding, and education, the Museum will educate

students as well as the general population about the uniqueness

of that event and its ongoing lesson: that humankind must learn

to live together in peace and harmony.[4]

Ellen Trachtenberg recalls, “We did not

know if people would come when we opened the doors.”[5]

Their worries were unfounded. From 1996-2002, the museum welcomed

nearly 550,000 visitors.[6]

The Houston museum’s emphasis on educating

students is in the mission statement itself and is reinforced by the

fact that no admission fee is charged to visit the facility. In 2002

alone, over 30,000 students toured the museum with a trained docent.

The Education Department reached another 338,000 students through

their curriculum trunk outreach program.[7]

This program provides a comprehensive curriculum for teachers to utilize

in elementary, middle, and high school language arts and social studies

classrooms throughout the world. The museum has sent these trunks

to such countries as Afghanistan, Belgium, Bosnia, Germany, and Italy.[8]

The Education Department provides age-appropriate lesson plans and

materials, including multimedia tools, at no cost to the schools and

teachers. They also provide annual teacher trainings for those interested.

The Holocaust Museum Houston staff believes very strongly that lessons

can be drawn from studying the Holocaust and they direct great efforts

to teaching these lessons to young people so that the memory of the

Holocaust will survive. While this museum is modest in size, its

goals are lofty. Presently, the museum staff is working to create

a statewide Holocaust Education Mandate to ensure that “every Texas

child will be educated in the lessons of the Holocaust.”[9]

This museum’s dedication to education, especially that of today’s

youth, makes it an excellent case study for an analysis of youth Holocaust

education in the United States.

In several ways, the Museum of Tolerance

is the direct antithesis of the museum in Houston. Located in Los

Angeles, California, not far from the Hollywood Hills and Rodeo Drive,

this museum has adopted a high tech format to teach students about

the Holocaust. Originally, the museum was affiliated with Yeshiva

University. When the State of California appropriated $5 million

for the museum in 1985, the ACLU filed suit against the state for

violating the separation between church and state. Once the two institutions

formally separated, the court rejected the ACLU’s plea and awarded

the $5 million grant to the museum.[10]

With these funds and many other private donations, the museum began

its construction. Its enormous 165,000 square foot building houses

two large exhibition halls, a separate artifact room, a multimedia

center, and spaces for rotating exhibits.[11] The Holocaust Museum Houston is quite

modest in comparison, utilizing all 18,000 square feet of its floor

space for the main exhibit hall, rotating exhibit hall, theater, classrooms,

and library and archives.[12]

Since its opening in 1993, many stars and

high profile politicians have been seen at fundraisers for the L.A.

museum and events promoting one of its main themes, eradicating racism

and prejudice in the U.S. and worldwide. They see nearly five times

as many students per year as the Houston museum, but also charge $6

per student. Programs, such as Investing in Diversity, help fund

Title 1 schools’ field trips to the facility, and the museum is committed

to the idea that they will not turn anyone away.[13]

Considering itself as the educational arm of the Simon Wiesenthal

Center, which is firmly committed to promoting human rights, the Museum

of Tolerance is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Holocaust

while promoting human dignity.[14] This is conveyed in the museum’s mission statement:

The Museum of Tolerance is a high-tech, hands-on

experience that focuses on two themes through interactive exhibits:

the dynamics of racism and prejudice in America and worldwide, and

the history of the Holocaust—the ultimate example of man’s inhumanity

to man.[15]

The directors of the museum are forthcoming

in their objectives and do not shy away from their focus on “racism

and prejudice.” However, this has led scholars to present a number

of critical assessments of the museum.[16] Since its inception, the Museum of Tolerance has received

mixed reception from academics who see this emphasis on tolerance

rather than history as detrimental to the study of the Holocaust and

the propagation of its memory. Since the museum opened, exhibit

designers modified some exhibits and completely eliminated and replaced

others. While the Associate Director of the Museum states that these

changes were made because of their “commitment to making it more relevant

to current situations,” one wonders whether any of these changes were

made in response to the numerous critical reviews.[17]

The name of the museum itself was another of the changes made. While

it used to be referred to as the “Beit HaShoah-Museum of Tolerance,”

which means “house of the Holocaust” in Hebrew, any reference to the

Holocaust itself has been dropped from the museum’s name. Despite

negative views of this museum among scholars, the majority of the

general public and press have had wonderful things to say. Even

The Oprah Winfrey Show recently featured and praised the museum

for its work.

The Holocaust Museum Houston and the Museum

of Tolerance are two very different institutions, not only in their

physical appearance, but in their methodology as well. The media-centered

approach in Los Angeles differs greatly to the more artifact-focused

exhibits in Houston. Regional differences are apparent in the exhibits

and programs at both museums. The Houston museum’s emphasis on local

survivors creates a community-based atmosphere for visitors. The

visitors from the Houston area feel a type of shared memory, realizing

that their neighbors went through the events they are learning about.

The Museum of Tolerance’s substantial use of technology throughout

the exhibition halls seems appropriate for a museum located so close

to the Hollywood Hills. The abundance of media that is reminiscent

of Hollywood—cell phones, computers, television—is reiterated by the

high-tech exhibits. In addition to the regional differences, the

L.A. museum has received a great amount of attention, while the Holocaust

Museum Houston has not received the same interest among academics

and the press.

Despite all differences, one can discern

some similarities. They have similar goals as evident by the focus

on teaching lessons maintained in their mission statements. Both

museums highlight certain themes, such as prejudice and racism, throughout

the exhibits and programs. These non-profit museums both sit in the

center of very large metropolitan areas and place a great emphasis

on their education programs for young people. Many Jewish students

attend these museums on class field trips, but both museums aim especially

to bring non-Jewish students into their institutions. They have

also placed an age requirement for student tours, discouraging groups

of students below grade six from visiting the exhibits, although they

do provide alternative programs for these younger students. While

their style and methodology are very different, the Holocaust Museum

Houston and the Museum of Tolerance aspire to achieve similar goals

by teaching the history of the Holocaust and its lessons.

The memorialization and commemoration of

the Holocaust in the United States did not emerge immediately after

the concentration camps were liberated in 1945. Decades passed before

the horrific atrocities that took place under the Nazi regime entered

into the collective memory of the American public. By the 1970s,

silence gave way to an intense interest. This Holocaust consciousness

led to and was inspired by the creation of numerous Holocaust memorials,

museums, and education centers across the United States. In San

Francisco, survivors of Nazi Germany and Jewish community members

founded the Holocaust Library and Research Center in 1979, which was

later renamed the Holocaust Center of Northern California.[18] In 1984, the Holocaust Memorial Center in West Bloomfield,

Michigan opened its doors as the first freestanding Holocaust museum

in the U.S.[19] The growing interest in remembering the Holocaust has

also been paired with an interest in studying and teaching the Holocaust.

Scholars have explored three central questions: Why has the Holocaust

become central in American consciousness in recent years? How has

the Holocaust been interpreted in relation to the larger historical

context? How have American ideals shaped the ways that the Holocaust

has been taught?[20]

There has been a

plethora of studies examining the emergence of this “Holocaust consciousness,”

not only in the countries in which the events took place, but in the

United States as well. Once the general public became interested

and began to discuss the Holocaust in popular culture, through movies,

television, literature, and museums, a new field of Holocaust studies

appeared. Scholars began to analyze not only the Holocaust itself,

but also the emergence of Holocaust consciousness itself and its place

in American society. They grappled with the question of why intense

interest in the Shoah became so prevalent here so suddenly in the

1960s, especially since the vast majority of America’s population

was not directly, or even indirectly affected by the events. Historian

Omer Bartov emphasizes that one result of having Holocaust memorials

and museums in the United States, is a greater potential to universalize

the Holocaust as an event from which a variety of lessons can be drawn.

[21] Is the Holocaust

a universal event that can be taught in a broad historical context,

or is it a unique event, without any comparison and any lessons?

These debates have shaped the ways in which the history, causes, and

circumstances leading up to the Holocaust have been taught in schools

and museums.

The historical facts of the Holocaust are

not the only topic, or even primary issue, emphasized within museum

and school curricula. Holocaust educators also emphasize the lessons

that can be learned from this event. The lessons found in Holocaust

museums in the U.S. often reflect core ideals of American society—liberty,

freedom, and pluralism—revealing the trend to “Americanize” the Holocaust.

The idea that lessons can be extracted from the Holocaust has led

to some criticism, on the grounds that lessons are not usually found

in extreme cases of events or situations, but instead are found in

more normal situations to which normal people can relate.[22]

Regardless of these criticisms, the Shoah is being taught in schools

and museums across the nation and many efforts are made to draw lessons

from these horrifying events. Many believe that a future holocaust

could be prevented if proper education on the dangers of intolerance,

racism, and prejudice is administered across the U.S.

While scholars have contributed extensive

research to the field of historical memory and Holocaust studies,

they have given little attention to the role that historical memory

plays in museum education. The surveys of curricula have been brief

and sporadic in Canada and England, and even less has been done in

America.[23] A survey of American textbooks by Lucy

Dawidowicz is over a decade old, and as new curricula are developed

and old ones are improved, there is a manifest need for additional

exploration of these texts.[24]

Scholars have developed three main arguments

to explain why the Holocaust was not discussed immediately after the

liberation of the camps in either public or private contexts. Some

scholars see the silence as a result of the trauma and subsequent

repression that stemmed from the horrific images and events of the

concentration camps.[25] Others

agree that the survivors themselves kept quiet because of the trauma

of their experiences, but do not see the collective silence of both

American Jews and non-Jews as a result of this trauma. Peter Novick,

a leading scholar in the field of Holocaust commemoration, argues

that while most Americans were probably shocked, dismayed, and saddened,

there are other explanations for their silence.[26]

Edward Linenthal, another scholar in the field, attributes the silence

to underlying guilt among American Jews for not doing more to help

as Europe’s Jews were perishing in the concentration and extermination

camps.[27] Other scholars claim the desire to focus on seizing

personal and financial opportunities in post-war America came to be

the driving force in evading public discourse on the atrocities of

the Holocaust.[28] Survivors

who immigrated to the U.S. especially wanted to rebuild their lives

and turn their attention towards the future instead of dwelling on

the past. A feeling of success spread throughout American culture

after the war ended, and the nation wanted to focus on the Allied

victory and the bright future that lay ahead.

Although there were many reasons to remain

quiet about the traumatic events of the Shoah, an accumulation of

events and circumstances eventually broke this continued silence.

Just as debate continues today over the causes of the silence, discussion

is also present regarding the breaking of this silence. Most agree

that the political climate in the U.S. was a major contributing factor.

Peter Novick argues that many circumstances in the 1960s and 1970s

that affected American politics and society, such as changing attitudes

towards victimhood, shifting positions towards the acceptance of ethnic

differences, and the Middle East conflicts, greatly contributed to

the emergence of interest in the Holocaust. The Vietnam War and the

Civil Rights movement helped to combat the notion that victimhood

equaled weakness. Novick argues that a more sympathetic outlook developed

that accepted and even celebrated victimhood. A new spotlight on

spousal and child abuse also emerged at this time, revealing this

shift in attitude towards victims.[29]

Just as the idea of victimhood came to be

acceptable in American society, a greater toleration of ethnic differences

also developed. The decline of an “integrationist” agenda in the

U.S., and the rise of a “particularist ethos” which emphasizes the

differences between Americans, contributed to the notion that is was

acceptable to embrace one’s ethnic differences and display them proudly.

[30] American Jews no longer

felt the pressure to assimilate into their surrounding culture, and

began to incorporate the Holocaust as a defining factor of their collective

Jewish identity. This also helped to strengthen Jewish continuity

in America, at a time when intermarriage was rising and religiosity

was declining. American Jewish identity became intertwined with Holocaust

memory and many Jews began to see it as their duty to commemorate

and memorialize the Shoah in mainstream America.

In addition to these factors, nearly all

scholars agree that the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann greatly

increased awareness and popular interest in the U.S. In 1961, Hannah

Arendt’s articles in the New Yorker and in her subsequent book,

Eichmann in Jerusalem provided gripping accounts of the trial,

making it front-page news in America.[31]

She helped to bring the horrors of the genocide back into the public

eye, and these issues could no longer be avoided. For Americans,

Eichmann symbolized more than a Nazi perpetrator. Even after his

trial ended and throughout the 1960s, Eichmann’s role in the genocide

remained in the American conscience. Later in the decade when anti-Vietnam

War sentiment was increasing, protestors put his name on banners since

his story embodied the current conflict of individual conscience versus

obedience to authority.[32]

The fate of Holocaust consciousness was

imprinted into the minds of Americans during a short span of six days

in 1967. Scholars have marked the Six Day War as one of the defining

moments of Holocaust awareness and interest.[33] On May 26, 1967, after mobilizing his army, Egyptian

President Gamul Abdel Nassar stated that the destruction of Israel

was his main goal.[34] The

fear that the Jewish people would be faced with another holocaust,

struck deep into the Jewish and non-Jewish communities in America.

People began to think that by remembering the Shoah and attempting

to understand why and how it happened, history could be prevented

from repeating itself.

Throughout the 1970s, Holocaust consciousness

continued to increase across America. During the Yom Kippur War in

1973, the fears of Israel’s possible destruction resurfaced, and concern

with commemorating the Holocaust became manifest.[35] Then in 1978, two landmark events took place, which

brought the Holocaust to the forefront of American popular culture

and politics. The airing of the NBC miniseries Holocaust brought

the horrifying events into the living rooms of all Americans and broadened

the scope of consciousness to non-Jews as well. In addition, during

that year, President Carter formed a commission to recommend the creation

of a national memorial to the Holocaust.[36] This initiative ultimately resulted in the creation

of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, located on the Mall

in Washington, D.C. The location of this memorial to Europe’s murdered

Jews is very symbolic as it indicates that the Holocaust has been

incorporated into American history and identity.

As the public began to discuss the Holocaust

in many arenas, including the media, universities, museums, and popular

culture, the events were analyzed, and debates emerged regarding how

the facts should be interpreted. Is the Shoah a unique and unmatched

occurrence, without any comparison, or is it a universal event with

implications throughout history and for today’s society? Are there

lessons or messages that can be taken from the senseless murder of

11 million human beings? This issue of defining the Holocaust as

either a unique or universal event in history becomes especially important

in regard to Holocaust education.[37] The ways that the events are perceived shape how the

story is told.

Many survivors tend to argue for the uniqueness

of their experiences, setting it apart from other historical events

entirely. However, in the process of historicization, the mass murder

of millions of Jews is inevitably subject to comparisons with other

genocides in history. Might such comparisons deny the uniqueness

of the event and trivialize the crime? In their article “Two Kinds

of Uniqueness,” Professors Alan Milchman and Alan Rosenberg argue

that the uniqueness of the Holocaust can only be recognized through

comparisons with other genocides.[38]

This can be a problem in Holocaust curricula, as teachers often place

the Shoah into the larger framework of human rights violations, racism,

and intolerance, but often neglect to focus on the role of anti-Semitism.

While this emphasizes that lessons can be drawn from the Holocaust,

it negates the important notion that this genocide was very different

from other genocides throughout history. Many people believe strongly

that the Holocaust was either a unique or a universal

event. However, some scholars are now bridging this gap and stating

that neither is entirely correct. The Shoah can neither be “marginalized

as an aberration” nor “contextualized as a part of human progress.”[39]

Milchman and Rosenberg use the term “caesura” to explain the events

as neither universal nor unique, but instead as an interruption in

human history that must be studied. Regardless of which view is accepted,

the presence of competing views makes the narrative even more complex

for educators, who have to create an account that will be accepted

and understood by many.

Also adding complexity to the role of educators

in Holocaust museums is the notion of the “Americanization of the

Holocaust.” This phrase is used in almost all of the scholarly works

on the commemoration and representation of the Shoah mentioned above

and refers to the aspects of American society that have influenced

how the Holocaust is taught.[40]

In his study of Holocaust memory and memorials, James Young argues

that memorials remember the past according to the “national myths,

ideals, and political needs,” and therefore, U.S. memorials remember

the past according to specific American ideals and values.[41]

This is evident in museums, as well as memorials.

Both have shaped the story of the Holocaust to incorporate the ideals

of “pluralism, tolerance, liberty, and human rights.” [42]

Many museums put forth this agenda, in particular the Beit HaShoah-Museum

of Tolerance. The name of the museum itself illustrates how American

values are being incorporated into the museum narrative. Michael

Berenbaum, the former deputy director of the President’s Commission

on the Holocaust, has even stated:

[T]hroughout the United States, instruction in

the Holocaust has become an instrument for teaching the professed

values of American society: democracy, pluralism, respect for differences,

individual responsibility, freedom from prejudice and an abhorrence

of racism.[43]

This helps to create an atmosphere that

will resonate with all the different types of people in America who

visit the various Holocaust museums across the U.S. While this process

of “Americanization” has received some criticism for trivializing

a sacred event, it is mostly the mass media, literature, and tourism

that have received the greatest critical assessments, while most critics

have spared museums. The museums, for the most part, have been created

as places of remembrance and learning, while also retaining this very

“Americanized” focus towards ideals of liberty and pluralism.[44] President Carter reiterated this notion

at the first “Days of Remembrance” ceremony when he gave three reasons

for the justification of a national memorial to the Holocaust here

in the U.S.:

Although the Holocaust took place in Europe, the

event is of fundamental significance to Americans for three reasons.

First, it was American troops who liberated many of the death camps,

and who helped explore the horrible truth of what had been done there.

Also, the United States became a homeland for many of those who were

able to survive. Secondly, however, we must share the responsibility

for not being willing to acknowledge forty years ago that this horrible

event was occurring. Finally, because we are humane people, concerned

with the human rights of all peoples, we feel compelled to study the

systematic destruction of the Jews so that we may seek to learn how

to prevent such enormities from occurring in the future.[45]

President Carter projected the notion of

the United States as a haven for the oppressed and a land of “humane

people” who see it as our duty to uphold the freedoms of others for

future generations. He also indicated that by studying about the

Nazi genocide, we could learn how to prevent future atrocities from

occurring. It is for this reason that many museums and education

centers have been created, with the goal of remembering the Holocaust

as well as preventing another genocide from happening.

Just as Holocaust consciousness in the U.S.

was growing in the 1970s, the role of education in museums was expanding

tremendously. The American Association of Museums (AAM) recognized

the need to establish specific minimum standards for all museums.

In 1975, the AAM broadened its definition of a museum with two main

goals in mind—to entrust those institutions in educating the public,

and to create a greater level of professionalism among museums.[46] The importance of education in museums

continued to grow and by the early 1980s, exhibition development teams

began to include museum educators. By 1992, the AAM published the

first major work identifying the educational role of museums, entitled

Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums.

This report argues that a museum’s commitment to education should

be central in its mission and pivotal to all its activities.[47] Practitioners began to gather and discuss the new role

of museum educators. A clear definition of the collective role of

a museum educator soon emerged:

The educator establishes the link between the

content of the exhibit and the museum audience. The educator is a

communication specialist who understands the ways people learn, the

needs that museum audiences have and the relationship between the

museum’s programme and the activities of other educational institutions

including schools. The educator plans evaluation activities that

will examine the exhibit’s success in meeting its intended objectives

and communicating with visitors.[48]

Traditionally, schools and museums have

established close relationships. Teachers see museums as a place

to expand upon their in-class lesson plans and to fill in areas they

left out. The students relate their museum experience closely with

school, however it is a new venue for them to explore, making a museum

field trip even more interesting and full of possibility.[49]

If the museum educator is able to establish the connection between

the exhibit and the student, as the above description states, class

visits to a museum can entice students to expand upon the knowledge

they acquired in their museum visit. Serving as a catalyst to increase

students’ knowledge and interest in a subject, museums can become

a central part of youth education.[50]

Because Holocaust museums have taken on

the task of educating America’s youth about the Holocaust and the

lessons that can be learned from the history, museum educators are

left with a difficult job. How much can museums be expected to teach,

and students expected to learn, in a short several-hour visit? Practitioners

and scholars in the field of museum education have grappled with this

issue extensively. Scholars argue that for visitors to learn in museums,

they must encounter topics and displays relevant to their own personal

lives and interests.[51] Thus, for students to connect during their short visit

to the museum, they must see the information being conveyed as important

for their own lives. Michael Berenbaum, former project director

of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, has often stated that

the message these museums are telling must resonate with its audience

so they can relate.[52] By situating the Holocaust in a historical context that

Americans can relate to, Holocaust museums can reach its audience

and establish a connection that will promote learning. Some scholars

have taken issue with this notion, as Alvin Rosenfeld argues that

American social problems are not genocidal in nature and do not resemble

the persecution and systematic genocide that was the Holocaust.[53]

Regardless of criticism by scholars, museums have accepted the idea

put forth in the museum education field—for students to learn in the

museum, they must be able to relate. Educators in Holocaust museums

apply this idea not only to the education programs they create, but

also in the exhibitions themselves. The growing importance of educators

to these museums has influenced the ways that students are now being

taught about the Holocaust.

|

|

Before visiting museums, packets of information

are sent to teachers to help prepare for their visit and also supplement

their pre- and post-visit lesson plans. At the Holocaust Museum Houston,

the teacher packet provides a general list of guidelines, vocabulary

terms, timelines, maps, quotations, and a suggested reading list.

In addition to these resources, one page is dedicated to the question,

“Why teach the Holocaust?”[54] Teachers must address this question and develop

a solid rationale for teaching the Holocaust long before the lessons

or field trips begin. Holocaust educators Samuel Totten, Stephen

Feinberg, and William Fernekes argue that without strong underlying

principles, the lessons and units lack an appropriate historical focus

and concentrate solely on the “whats” of the history, instead of the

“whys.”[55] The

Houston museum’s teachers’ guide continues to ask, “How can we not

teach it?” It goes on to argue that the study of the Holocaust will

be extremely pertinent to the students’ lives, as they make connections

between history and current moral decisions they will be faced with.

The guide also emphasizes that this history should not solely be studied

by Jews, but rather is relatable to all students and will promote

a more positive approach to different cultures.[56] However, the guide does little

to further this notion of fostering more positive attitudes towards

other minorities. In response to its question, “How can we not teach

it?” the guide states that by “studying the past… [the students] become

aware of the importance of making choices and come to realize that

one person can make a difference.”[57] The educators and docents carry this theme

throughout the students’ visit and strongly emphasize the importance

of individual choice and free will throughout their museum experience.

The educators argue that students should view themselves as active

individuals, not bystanders, who possess the ability to control their

actions and the choices they make. Despite the devastating and incomprehensible

nature of the Holocaust, lessons can be learned by studying it and

students can take away ideas that might help them live better lives.

To further provide historical context for

students, a vocabulary list of general Holocaust terms, as well as

terms about Judaism, helps to familiarize the students with the Jewish

religion and people and places involved with the Holocaust.[58]

The focus on Jewish religious terms provides students, the vast majority

of whom are not Jewish, with a general background so they can recognize

certain artifacts at the beginning of the permanent exhibit and understand

terms used by the docent. In the early planning stages of the museum,

the Holocaust Museum Houston Permanent Exhibition Committee decided

that attention must be directed to the pre-Holocaust history of the

Jews, to show how rich their culture was and to highlight how much

was truly lost.[59] This helps to place the long

history of Judaism and anti-Semitism into a historical context. Also

provided are prejudice terms—stereotype, prejudice, racism, discrimination,

anti-Semitism, genocide—and related questions for discussion on these

topics. While they list only six general prejudice terms, 64 Holocaust-

and Judaism-related vocabulary words are provided. A comprehensive

timeline ranging from 1933-1945 includes not only events directly

related to the Holocaust, but also events that students may have already

been aware of, such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Allied

invasion of Normandy. Issues also included are the revolt of inmates

at Auschwitz, the attempt to assassinate Hitler, and the Warsaw ghetto

uprising, in addition to armed resistance in other various ghettos,

and the Sobibor extermination camp. The guide also discusses the Jewish

partisan movement. To expand upon the theme of resistance, a detailed

map indicates all Jewish revolts between 1942 and 1945 and highlights

that “[d]espite the overwhelming military strength of the German forces,

many Jews… rose in revolt against their fate” (fig. 1).[60] Again, the educators are able to incorporate the theme of individual

choice.

|

Figure 1. Map of Jewish revolts

in the Holocaust Museum Houston Teacher Packet. |

They also stress the importance of including

a comprehensive look at resistance to the Holocaust prior to the students’

visit, in order to debunk prejudices that the “Jews went like sheep

to the slaughter.” Geoffrey Short argues this point, stating that

teachers should address any and all misconceptions students might

have about Jews or the Holocaust before their visit. By providing

materials to study and discuss in the classroom, this goal can be

achieved.[61] The

timeline also illustrates the progression of Hitler’s policies that

deprived Jews of their rights, their dignity, their freedom, and ultimately

their lives. The timeline was taken in part from the book, Genocide:

Critical Issues of the Holocaust, which is a Simon Wiesenthal

Center publication. The Holocaust Museum Houston teachers’ guide

also utilizes the list of frequently asked questions about the Holocaust

compiled by the Simon Wiesenthal Center. However, the Houston guide

abbreviates the list of 36 questions to twelve selections that address

very broad concepts that docents expand upon during the tour. Even

though Houston educators utilized information from Simon Wiesenthal

publications, they saw the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

as a greater influence in the development of their education programs.[62] |

|

Figure 2 |

Museum

of Tolerance |

Holocaust

Museum Houston |

| Number

of Terms |

% of

Total |

Number

of Terms |

% of

Total |

| Judaism

Terms |

2 |

15.4% |

15 |

21.4% |

| Holocaust

History Terms |

1

|

7.7% |

49 |

70.0% |

| Prejudice

Terms |

10

|

76.9% |

6 |

8.6% |

|

|

Figure 2.

Analysis of vocabulary words provided in both museums’ teachers’ guides. |

|

The Museum of Tolerance educators recommend

that teachers begin preparation for their visit by discussing the

vocabulary and concepts they will encounter in the museum. Few of

the vocabulary terms they provide for teachers relate directly to

the Holocaust. The majority of terms relate to racism, intolerance,

and genocide in general (fig. 2).[63]

In a pre-visit lesson plan provided to teachers

entitled, “Essential Vocabulary and Concepts,” thirteen terms are

discussed and only one is Holocaust history-related. The lesson plan

consists of a word match and a column of scenarios that refer to the

vocabulary terms provided—prejudice, racism, genocide, stereotype,

and discrimination. Only one scenario deals directly with the Shoah

stating, “Nazis try to kill all Jews,” which matches with the term,

genocide. The other scenarios refer to instances that students might

commonly identify with, such as people blaming innocent Arab Americans

for terrorist attacks.[64] While the educators hope that students can

put these terms in the framework of their modern lives, the lesson

plans and teachers’ guide do not discuss how such terms as prejudice,

stereotype, discrimination, and racism relate to the Holocaust. They

might understand what racism is, but not in the context of Nazi Germany

or the Shoah.

The Museum of Tolerance educators developed

thirty-six frequently asked questions and answers, in which more terms

relating specifically to the Holocaust can be explored. This comprehensive

list of questions provides a great deal of information and would be

most appropriate for teachers and students to explore prior to the

visit. This guide focuses on certain topics, such as when the first

concentration camp was established, why Jews were singled out for

extermination, how much Jews in Europe realized what was going to

occur, how much the German people knew about what was happening to

their Jewish neighbors, how much the Allies knew about what was happening

in Nazi Europe, and what the attitude of the church was towards the

Nazi regime.[65]

Unfortunately, the main exhibit in the Los Angeles museum does not

reinforce much of the information presented in these questions. In

some cases, the exhibits skip over entire questions and in other parts,

the questions are briefly discussed. It is therefore up to the teachers

to teach their students all the history of the Holocaust before they

step into the museum.

The Museum of Tolerance also developed four

themes and learning objectives that students see throughout the museum—the

power of words and images, the dynamics of discrimination, the pursuit

of democracy and diversity, and personal responsibility. The museum

illustrates how their themes relate to the California State Frameworks

and Content Standards.[66] Throughout the year, teachers must achieve certain goals set

by the state, and the museum is careful to show that the students

will not fall behind if they add a lesson on the Holocaust and tolerance

to the curriculum. Again, the teacher is supposed to contextualize

the history and prepare his/her students. As the Associate Director

of the Museum of Tolerance pointed out in an interview, the materials

provided for teachers are seen as “trigger lessons,” meant to be stepping-stones

for further research and learning on the teacher’s part.[67] To facilitate further learning

among teachers, the museum maintains an interactive web site in which

teachers can post messages and share ideas for teaching about the

Holocaust. The Museum provides workshops to better prepare teachers

to provide appropriate lessons for their students. These workshops,

however, focus mainly on tolerance-related issues.[68] While the museum provides what seems to be

a vast array of resources for teachers, it still relies on teachers

to prepare students for the visit. Once they enter the museum, the

students are in the hands of the museum educators.

| |

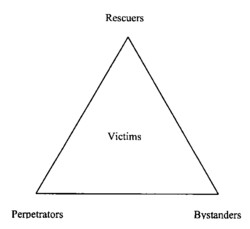

| Figure 3. Museum staff utilize this diagram to

begin discussion about the Holocaust. |

Despite all the preparation, the ultimate

question is how this translates into learning and understanding once

in the museum. At the Holocaust Museum Houston, students are immediately

escorted to a classroom and met by a staff visitor coordinator. This

staff person provides an orientation to the museum and introduces

the docent(s) who will be guiding the students through the museum.[69] The staff person begins by

directing students’ attention towards a diagram fixed to the front

center of the classroom. Students look at a triangle, with the words

rescuers, bystanders, perpetrators affixed to each corner and victims

inscribed in the center (fig. 3). They begin to discuss how each

of these groups participated in the Holocaust, and how only one group

had no choice—the victims. The staff person emphasizes that the rescuers

and perpetrators were very small groups while the bystanders constituted

the vast majority of people. “We all have a choice, and this is why

you are here” is the last phrase left in the minds of these young

students before they begin the tour. The students will revisit this

theme throughout their visit, not only in the context of Nazi Germany,

but in their own lives as well. As the students go off with a docent,

the staff person reiterates that the museum is also a memorial, and

therefore needs to be treated with the respect that a church, temple,

or synagogue would.

As the groups move into the exhibit hall,

the docent notes how the design of the space evokes a certain emotion

and symbolizes some part of the Holocaust. The materials used in

the construction of both the interior and exterior—steel, brick, concrete—suggest

a feeling of somberness and the industrialization of the camps.[70]

While standing in the lobby and gazing down the hall towards the memorial

garden, the students see steel beams over-head slowly becoming narrower.

The hallway itself also becomes more narrow and the image of a railroad

track leading to Auschwitz is immediately conjured up. For the students

who do not immediately notice the metaphorical nature of the architecture,

the docent spends a few minutes discussing the structure. He/She

also tells students to notice the shape of the room they are about

to enter.

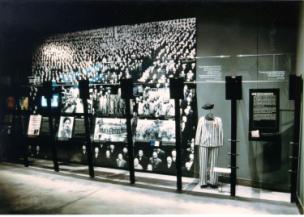

The permanent exhibit hall, which is the

wedge-shaped building visitors see as they arrive, begins with a high

and open ceiling when telling the history of Jewish culture in Europe,

but it progressively becomes lower as the story shifts to the slaughter

of the Jewish people. The exhibit designers incorporated multiple

forms of media to tell the story of the Holocaust. A combination

of enlarged black and white images, text panels, artifacts, reproductions,

maps, and television screens are utilized throughout the hall. The

exhibit designers incorporated five television screens at different

points in the story; however, the only one in sound is film footage

of Nazi rallies and propaganda. During the planning phase, the Permanent

Exhibit Committee felt that it was very important for visitors to

hear Hitler’s charisma when he spoke and the “war-like” quality to

his voice.[71] Because

this is the only video clip with sound, the role of Nazi propaganda

takes on a greater importance. If a visitor recognizes this video

as the only one with sound, it conveys the message that Nazi propaganda

must have played a very important role in Hitler’s rise to power and

his continued popularity among the German people, even as he led them

to war. Even though monitors were not originally planned for, a

few were included that show archival images of the Warsaw ghetto,

concentration camps, and the liberation of the camps.

Unlike the mixed media approach presented

in Houston, the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles utilizes an abundance

of television screens to reach its goals of teaching about the Holocaust

and fostering tolerance. In justification for the excessive use of

TV images, founder Rabbi Marvin Hier asks, “Where are your kids now?”

He goes on to answer, “[t]hey’re at the computer and after that they’re

going to watch television. That’s the kids of America. This museum

wants to speak to that generation. We have to use the medium of the

age.”[72] In its attempt to create an

environment that appeals to the youth of America, the Museum of Tolerance

has subscribed to a view of today’s adolescence as unable and/or unwilling

to listen and learn unless material is presented in the form of television

images. The museum even hired media experts to create an environment

in which the viewer is constantly stimulated and never bored.[73]

Unlike most museums, it rarely employs text panels as a method of

communicating with visitors. Besides the plethora of television screens,

in its architectural style and appearance, the museum building lacks

metaphorical symbolism. This is quite different from most Holocaust

museums and memorials, with their striking visual impact and structural

significance.[74] From the outside, the structure stands as a tall eight-story

building comprised of blank stone and glass and is “nothing special

architecturally,” as one critics points out.[75]

Once inside, an unusual structural feature is a Guggenheim-like spiral

ramp that leads to the exhibit halls. While docents and other museum

staff do not allude to any significance of this spiral structure,

I would argue that the architecture is symbolic. Visitors descend

down the staircase into a hell-like experience—the Holocaust—and then

reemerge, arising with the knowledge after learning in the exhibits.

|

|

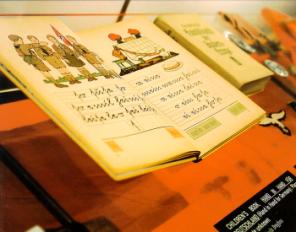

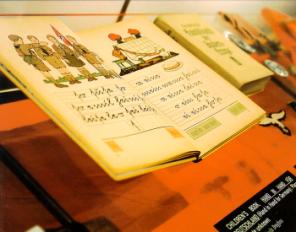

| Figure 4. If time permits, students

explore such items as Anne Frank's diary pages and a concentration

camp bunk bed (courtesy of the Museum of Tolerance). |

Among the exhibit halls is the museum’s Multimedia

Learning Center, which contains over thirty computer workstations for

visitors to explore the history of World War II and the Holocaust in greater

depth. Once again, the museum utilizes a technologically focused approach

to learning. However, most class tours are pressed for time and rarely

have the opportunity to visit this exhibit, unless the teacher makes special

arrangements. Docents often encourage students to return with their parents

at another time to explore the museum and all the sections they were unable

to discuss due to time constraints. The classes that sign up for a special

program called “Steps to Tolerance” have the opportunity to spend time

in the Multimedia Learning Center. This program is solely for fifth and

sixth grade students, and they spend their 2-½ hour visit solely in the

Center learning about the Holocaust and contemporary issues of tolerance

and diversity in an age-appropriate way for younger students.[76] These students do not visit the main exhibit

hall.

Adjacent to the Center is the museum’s collection

of artifacts and documents (fig. 4). Tucked away from the abundance of

technology, this room provides a more conventional approach to museum

learning. This is the only place in the museum where visitors find actual

artifacts. Unfortunately, many students do not have the opportunity to

view these during their tours, once again due to time constraints. Students

spend the majority of their museum field trip in the Tolerancenter. There

are many different stations in this part of the exhibit, and if the docent

does not hurry students through certain stations, they have little to

no time to explore the artifact room.

The separation of mediums—television screens,

photographs, artifacts—in the Museum of Tolerance is very different than

the balanced mix of mediums found throughout the Holocaust Museum Houston.

The balance that is found in Houston can be seen not only in the physical

space of the museum, but in the teaching of the history and its lessons

as well. The history of the Holocaust and the lessons that can be learned

are balanced throughout the exhibit hall. In contrast to this balance,

the Museum of Tolerance has allotted the majority of space and time to

television screens and other technological accoutrements. Because the

museum designers incorporated this abundance of technology in the main

exhibit hall, they had to sacrifice the use of artifacts. Many students

are unable to ever experience real artifacts because there is not time

during their tour. This is one of the first things that the Museum of

Tolerance sacrifices to reach its goal of providing a “high tech, hands-on

experience.”[77] Even though each museum utilizes different

approaches to their exhibits, the main issue that must be examined is

the content of the exhibits themselves.

The visitors’ lack of knowledge about the Shoah

before visiting these museums provides a major concern for Holocaust educators

and exhibit designers who work with limited time and space. James Young

expressed such concerns in response to the creation of the United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum:

I did not want all that non-Jewish America knew

about Jewish history to be the Holocaust. And I did not want all that

Jewish America knew about Jewish history to be the Holocaust. A thousand

years of European Jewish life is reduced to 12 terrible years—I think

that’s the great danger.[78]

Placing the Holocaust in a historical context

has proven to be an important facet of Holocaust education and can help

to minimize the concerns raised by Young. By learning about the history

of the Jewish people and the history of anti-Semitism, the student will

be better equipped to learn about the emergence of Nazism, Hitler’s racist

ideology, and the Nazi party’s new anti-Semitism. It also helps to counter

arguments raised by historian Lucy Dawidowicz that Holocaust educators

spend more time on teaching what happened, instead of on why it happened.[79]

Educator Mark Weitzman provides several guidelines for teaching about

the Holocaust, including the notion that it is crucial to “explore the

context within which the Holocaust occurred” and to “explore Jewish life

and culture before the Holocaust to gain a sense of the living community

which was destroyed.”[80]

Doing this helps to eliminate misconceptions that somehow the Jews were

guilty of something and deserved separation from society. Another scholar

rightly argues that students must understand that the Jewish people were

more than objects of genocide.[81]

The Holocaust Museum Houston’s teachers’ guide

highlights this issue and has a guideline stating, “[t]he teacher should

contextualize the history they are teaching… so that students may begin

to comprehend the specific circumstances that encouraged or discouraged

these atrocities.”[82]

As students enter the main exhibition hall in Houston, the docent begins

by pointing out a variety of religious artifacts that survived the war,

as well as some that belonged to survivors. Directing students’ attention

towards a salvaged Torah scroll, the docent provides a brief background

into the Jewish religion and the Hebrew Bible. This helps to emphasize

the differences between race and religion. This issue is discussed further

as the docent highlights differences between Nazi racism and previous

forms of anti-Semitism. He/She reiterates that Hitler did not invent

anti-Semitism, nor did the German people, but that it stems from a long

history. On one side of the entrance corridor, the students examine a

large map of the world, which highlights various occasions of discrimination

against Jews (fig. 5).

|

Figure

5. Various instances of anti-Semitism throughout history are highlighted

on this map of the world (courtesy of Holocaust Museum Houston). |

Among the many examples is a 306 AD edict

from a church council in Spain stating that intermarriage and intercourse

between Jews and Christians was prohibited . This serves as a reminder

to students that the roots of the Holocaust were embedded in centuries

of religious anti-Semitism and political inequality.[83] It is important, however, to emphasize that

Hitler’s anti-Semitism evolved from such previous forms, but was based

on racial and not religious terms. Despite critiques that a focus on

religion could obscure the notion that the Nazis defined Jews by racial

factors, it is central to the history of the Holocaust to understand how

the events came to take place.[84]

Next, students examine a wall of photographs,

and the docent explains that these are family photos of Holocaust survivors

who moved to Houston. The images portray Jews with a variety of religious,

geographical, and economic backgrounds. This helps to show that not all

Jews fit into the stereotypical categories presented by the Nazi propaganda

they are about to encounter in the museum. Pictures show well-fed, healthy

Jews before the war, and serve as a comparison to the images that are

associated with the victims of the Holocaust—emaciated, weaken bodies

barely holding on to life. By focusing on these photos and emphasizing

that these individuals could be their next-door neighbors, the museum

helps students connect and see those who lived during the Holocaust not

just as victims, but also as normal people who faced unimaginable circumstances.

The docent also points out an enlarged photograph of students standing

in rows with their teacher behind them. This photo is reminiscent of

the class pictures that students today take with their classmates and

teachers on picture day. Again, the students are able to relate to the

various people the museum presents in the exhibit.

Adapting parts of Mark Weitzman’s article for

its own use, the Museum of Tolerance’s website also highlights the importance

of exploring the context of the Holocaust and the Jewish life before the

Holocaust. Therefore, one should expect that visitors would receive

a proper introduction into the historical context in both these museums.

While the Holocaust Museum Houston provides a thorough background on the

history of the Jewish people, Germany, and anti-Semitism, the Museum of

Tolerance’s discussion is much more limited.

In contrast to the Houston museum’s exploration

of Jewish life before the war through photographs, religious artifacts,

and discussion with the tour guide, the Museum of Tolerance employs a

short video to describe “The Jewish World That Was.” Students watch this

video as they wait for their tour to begin in the computer-controlled

main exhibit hall of the Holocaust section. Prior to watching this video,

they receive a “photo passport” of a victim of the Holocaust to take through

the exhibit. Each student receives a driver’s-license-sized card with

a photo on it. Students insert their card into a computer at a station

at the beginning, middle, and end of the exhibit, which displays information

about “their person.” In some instances, the card is of a survivor; however,

the majority of the cards update the students with dismal information.

The short video that students are supposed to be watching at this time

is eclipsed by the excitement of their new interactive tool, as students

whisper to each other about “who they got.” The few students who do

pay attention to this film hear myriad Jewish and Yiddish terms, most

of which were probably not discussed in class prior to their visit, since

they were not included in the teachers’ guide. The narrator talks about

major European cities and the centers of Jewish learning and culture that

developed within each. Multiple images of Jews celebrating various religious

holidays and occasions reveal a narrow view of Eastern European religious

Jews, who wear black hats, long beards, and sidelocks. The story

briefly shifts to focus on the pogroms Jews faced, and how they still

managed to go on with their lives. While this film presents Jewish culture

as rich and fruitful, like the exhibit in Houston, it does little to dispel

any preconceived misconceptions about Jews and Jewish life. While the

majority of the Jews affected by the Holocaust were from Eastern Europe,

not all dressed this way and were religious.[85] “The Jewish World That Was” does not begin

to discuss how many Jews assimilated into their surrounding societies

and often felt a greater devotion to the country they lived in than their

religious heritage. An attempt to display other types of Jews spawns

a collage of famous Jewish faces, such as Felix Frankfurter, Albert Einstein,

Golda Meir, and of course the namesake of the museum, Simon Wiesenthal.

Although it is the explicit goal of the Museum

of Tolerance’s teachers’ guide to place the events in a historical context,

the exhibit does little to do this. In referring to why there is such

little background prior to the 1920s, the Associate Director of the Museum

stated that they rely on the teachers to contextualize.[86]

Regardless of whether students are properly prepared, many of the images

shown in this introductory video do little to dispel, and may possibly

even reinforce, stereotypes of Jews as aliens. Aiming to rid such stereotypes

is one of the claims the museum placed on its website as a guideline for

teaching about the Holocaust. However, it does not discuss the complex

history of Jewish persecution and anti-Semitism in this film. The short

video does display a facet of Jewish life before the war, but because

of time constraints, it discusses Europe in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries only very briefly. After the screening

is over, doors open automatically and visitors quickly move into the main

exhibit hall to begin their journey “back in time to become witnesses

to events in Nazi-dominated Europe during World War II,” as the teachers’

guide puts it.[87] The tour is just beginning and will subsequently

discuss many events that took place during the Holocaust. As Lucy Dawidowicz

pointed out, while the “whats” are incredibly important in studying the

Shoah, it is crucial to explore why and how those events happened as well.[88]

By providing information about Europe before

Hitler came to power, the Holocaust Museum Houston places the Holocaust

in a broader historical context. Many scholars have pointed to this as

one of the most important guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust,

because then students will be able to understand the history that contributed

to the mindset of those living during the Holocaust. When deciding what

events to include in the Holocaust section at the Museum of Tolerance,

exhibit designers decided to begin discussion in the 1920s. They had

to select certain events, and because time and space were minimal, specific

aspects of the history were either discussed briefly, or not discussed

at all. The video, “The Jewish World That Was,” was their attempt to

provide some historical context behind the history of the Jewish people

in the years before Hitler’s rise to power. This is another instance

where the Holocaust Museum Houston found a balance, and the Museum of

Tolerance made sacrifices to the teaching the history of the Holocaust.

Just as scholars have grappled with the question

of origins, museum educators have had to as well. While a contextualization

of Jewish history is crucial, museums must also explore how Hitler came

to power and how he was able to initiate his state-sponsored program of

genocide. The power of Hitler as an orator, as argued by both academic

scholars and museum educators, played a very important role in his ascent

to power. In addition, many other factors contributed to Hitler’s rise

to power, such as the economic conditions in Germany, its emergence as

an industrial center, and the previous years of history that shaped German

society.

The Holocaust Museum Houston provides a straightforward

and factual account of Hitler’s ascent to power, highlighting his early

anti-Semitic beliefs as propounded in Mein Kampf. It employs text

panels, artifacts, and docent instruction to detail the development of

Hitler’s anti-Semitism, from that of eliminationist to exterminationist.

The Holocaust Museum Houston effectively displays the economic and emotional

turmoil within Germany following World War I and the Treaty of Versailles.

However, little attention is paid to other influencing factors. There

is little to no background information provided on the history of Germany,

which would help to explain how so many Germans came to accept Hitler

and support his regime. By understanding the culture of militarism and

obedience to authority, which had been a long tradition in Germany, one

can better understand the variety of contributing factors that made the

Holocaust possible.[89]

The Houston museum subscribes

to the functionalist view claiming that the Holocaust was not inevitable

and was a process of decisions that eventually led to the genocide. Houston’s

visitor guide brochure states:

The Holocaust was not inevitable. Human decisions

created it and people like us allowed it to happen. The Holocaust reminds

us vividly that each one of us is personally responsible for being on

guard, at all times, against such evil.[90]

In reference to the museum’s approach, the Director

of Education pointed to parts of the exhibit that illustrate how the Nazis

first attempted to make life unbearable for Jews in Germany, then how

they tried to make Jews leave and through the various racial laws put

into place.[91] The Nuremberg Laws, passed in September 1935,

officially defined a Jew in strictly racial terms. Nazis began to consider

anyone with three or more Jewish grandparents to be a Jew. The laws

also deprived all Jews of their citizenship and prohibited marriage and

sexual relations between a Jew and a non-Jew.[92]

This view clearly reinforces the idea that the events of the Holocaust

were part of a process. This helps to convey the importance of personal

responsibility, a reoccurring theme in the exhibit. Because the events

of the Shoah were part of a process that culminated because of individuals’

actions and decisions, if students accept personal responsibility for

the events happening around them, they can help prevent history from repeating

itself. The Houston museum takes this opportunity to make sure the student

has a lucid understanding of what was happening in Germany in 1935. The

docent points out an artifact—a family tree class assignment—and discusses

how students in Germany were supposed to document their family’s racial

and religious background. Furthering the functionalist view, the museum

highlights the influence Hitler’s words had on the German people.

Docents assert repeatedly that Hitler was a charismatic

speaker and the visitors are able to witness this through archival footage

of Hitler speaking at a rally, the only video with sound used in the main

hall. Previously, when discussing Hitler’s early legislation, the docent

explains his actions as a suspension of civil rights. Again, when discussing

the Nuremberg Laws, he/she describes them as anti-civil rights laws.

The museum uses terms that the students will understand, as most have

learned about America’s civil rights movement throughout their elementary

and secondary educations. The student groups I toured with in Houston

felt a special appreciation for the plight of the Jews, as the school

was predominantly African American. They took their own understanding

of discrimination and racism against African Americans in this country

and applied it to their understanding of the progressive discrimination

against the Jews in Germany.[93]

The docent continues to relate to student visitors

by discussing the events of 1936. Highlighting the Olympics, docents

ask students if they know who Jesse Owens was. They all respond, “yes,

of course.” In the process of explaining how Germany had “cleaned up

its act” for the world to see in 1936, the docent also tells an anecdote,

explaining the story is more of a legend than reality. When Owens set

a new record, becoming the first American to win four gold medals in Track

and Field in a single Olympics, he went to shake Hitler’s hand, a formality

for the host country and gold medal winners. As the story goes, Hitler

refused to shake Owens’ hand because of his race. While this story may

or may not be true, and the docent clearly states that, it serves to bring

history closer to home for these students. It also clarifies the differences

between Hitler’s racial anti-Semitism and the religious anti-Semitism

they previously learned about at the beginning of the exhibit. Also helping

to explain the events in terms these students could relate to, the docent

called the process of Jews being moved to ghettos, “segregation like we’ve

never seen it.”

The exhibit especially provides a clear explanation

of the Evian Conference, which helps to eliminate the obvious question

of why the Jews did not leave Germany. In July 1938, representatives

of thirty-two governments met in Evian, France to discuss the plight of

Jews who were trying to flee Nazi Germany. At this conference, many countries,

including the U.S. and Great Britain, refused to alter their immigration

policies to let in any Jews.[94] By conveying to students that Jews had few

options at that time, students begin to realize that Jews did not in fact

“go like sheep to the slaughter.” The exhibit designers included a quote

that underscores the United States’ role in allowing the Holocaust to