Essay (back

to top)

Exploration of Nazism and Local Level Politics

The phenomenon of the Nazi takeover of Germany beginning in January 1933 eludes the grasp of many historians. Stories are told of a more than hypnotic Hitler, subduing the populace with his magnetic speaking and bellicose manner. Some point to Joseph Goebbels, the fabled God of Nazi propaganda, whose tireless dedication to the effort eventually secured the attention of all German society. To mention others would be superfluous because it is evident that such a personal, top down approach does not capture the real problem of how the Nazis were able to take control of the German political structure. This is why William Sheridan Allen takes a different approach in his book, The Nazi Seizure of Power. Using the pseudonym of Thalburg for an actual town in Germany, he proceeds with an exhaustive documentation of what transpired politically at the local level of that town to precipitate a turn towards such radically conservative politics.

To Allen, what accounts for the rise of Nazism in an otherwise sleepy, rather nonpartisan town, was the extraordinary ability of Nazis to organize at the local level, the inability of the SPD (Social Democratic Party) to formulate its own stance on the issues, and a general lack of knowledge among the populace as to what the Nazis actually intended to accomplish, all taking place against the backdrop of severe economic depression.

These three elements are most germane to the years 1930 – 1933, after which other elements became important in cementing the Nazi culture already present within the town, I ignore these other factors, however, as they occur after the Nazi party was in control of Germany. This method allows for a more effective examination of the dynamics of change from democracy to dictatorship, not the dynamics of further suppression of democratic tendencies and conformity to the new order. The following essay is broken down into four sections: local organization of the Nazi party in the beginning, reactions of the SPD and their inability to cope with growing Nazi popularity, the further enhancement of Nazi political efforts, and a description of the overall inability of the townspeople to grasp the full Nazi agenda.

Local Organization in Thalburg of the Nazi Party

In Thalburg, political activity consisted mostly of speechmaking in halls available for rent, parades, and less political events such as dances hosted by organizations with political affiliation. Political consciousness was reaffirmed daily, however, by the abundance of clubs in Thalburg organized around many different hobbies and professions, which overlapped, and could be broken down along class lines. (Allen, pp. 17-19) Most Nazi activity in Thalburg in early 1930 revolved around the Cattle Auction Hall, which was cheap to rent and small enough to hide a poor turnout. Although the rallies often did have such a turnout, they still managed to present a certain conception. Allen writes that one function of such activity, “was to demonstrate to Thalburgers that Nazis really believed in the ideas they preached.” He also writes that they appeared to be fervent patriots and avid militarists, as well as, “vigorous, dedicated, and young.” (Allen, p. 25, 28)

The first obstacle the local Nazi party faced was the election of 1930. How they prepared for this demonstrates the characteristics noted above. There were meetings every week, which featured notable speakers and discussions, and attendance was either full or standing room only. This was a change from previous years because the onset of depression made Thalburgers of all types more inclined to radical viewpoints. Leaflets were distributed and posters were all over the town, and for even broader appeal, a Lutheran pastor was brought in to speak on behalf of the Nazis. (Allen, p. 33) The result, locally, was cause for Nazi celebration as they attracted more than 800 new voters, and stole almost 1000 votes from various other parties (not the SPD), to increase almost fifteen-fold. (Allen, p. 34) This was a huge step towards the radicalization of Thalburg politics, and ushered in a new phase of Nazi campaign effort.

The Inability of the SPD to Combat Nazi Growth

It should be noted before anything else that the SPD was capable of achieving anything that the Nazis did. In the small town of Thalburg there was a Reichsbanner as well as an SA. There was a much larger meeting hall ( 1910er Zelt), which hosted SPD rallies. They were a formidable bloc in all areas of government, from the “city council” up to the Reichstag. What they failed to do, according to Allen, is two fold, first in their inability to recognize the Nazi party as a political threat, and second in their inability to separate themselves from an inconsistent appearance as both reformers and adherents to the status quo, which was necessary to capture the middle class (Burgher) vote.

Regarding the first point, Allen writes,

The Socialists undoubtedly felt, by the end of February 1931, that they were successfully meeting the Nazi challenge. The arrogance of the SA had been matched by the militancy of the Reichsbanner. Nazi charges were refuted, Nazi plots exposed. Every Nazi meeting or rally was countered by a Socialist rally. (Allen, p. 46)

What the SPD failed to realize was that beating the Nazis at their own game only frightened the Burghers into the perception of SPD dominance, which made them more and more receptive to appeals from the right. The SPD believed that the Nazis posed the threat of a coup d’etat, not of electoral defeat, and that politics was the business of “rational appeal and positive results”. Unfortunately for the SPD, Allen writes, “effective propaganda need not be logical as long as it foments suspicion, contempt, or hatred.” (Allen, p. 47)

The situation regarding the second point is more complex, but still surprisingly clear. Before the depression hit Germany, there was no incentive for the SDP to reach out to the Burghers. Burghers were the traditional opponents of worker solidarity and to do so would have risked the loss of the SPD’s core membership (workers), sending them to fringe groups such as the Communists (KPD). Once the depression worsened and it became clear a radical solution was necessary, suddenly the SPD was not radical enough. The author makes this point clear, stating, “No one believed that the Socialists would really attempt fundamental economic changes. Many blamed the [SPD] for not being radical enough (in economic matters)…Thus the SPD could not keep the middle classes from flocking to the [Nazis].” (Allen, p. 48) The SPD lost this battle in trying only simple opposition, and not producing any effective counter-programs to the Nazis. They could never appear to defend the old order or reform the new order as well as the Nazis could.

Hyperactive Mobilization of the Party at the Local Level

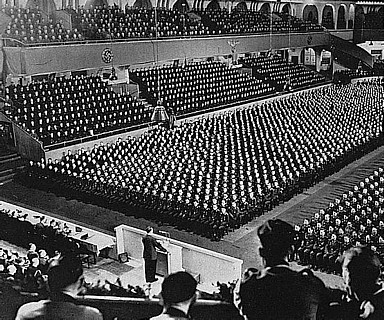

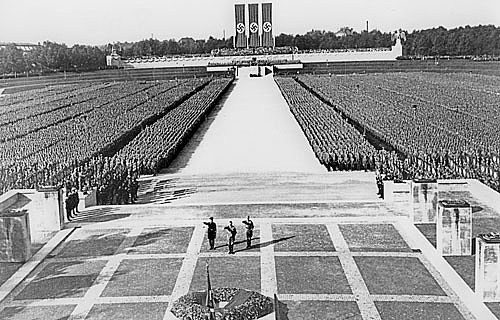

Nothing made the strength of the Nazi party more evident than the 1932 Presidential elections. While it would take much detail to go over the electioneering efforts of the other political parties, suffice it to say that they did not rival those of the Nazis. Instead of the usual tactics of meetings and speeches, they employed a practice of complete political saturation. Described by Allen it went as follows,

…the Nazis rented the 1910er Zelt for eight days running. Mass meetings were held on four different evenings, and daytime demonstrations were used to keep the town saturated with Nazi propaganda. It was an all-out campaign and it completely eclipsed the efforts of the opponents of Hitler. (Allen, p. 88)

There were enormous crowds, hour-long parades, and mass gatherings of thousands of SS and SA men. Allen goes onto say that it was “…a most impressive display of power, imaginations, and energy… This was an example of Nazi agitational and organizational ability at its best.” (Allen, p. 90) What followed was two more campaigns, one for the presidential run-off and the second for the election of a new Prussian parliament (which ran the stakes of breaking the SPD’s hold over that legislature). Through these campaigns were not as brilliant as the first in terms of pageantry, they were equally tenacious.

We can see then, from the numbers and from the authors own admiration for the events that the Nazis continued to display the same original tenacity they had when they rented out Cattle Auction centers to mask insignificant attendance. Whether it was 2%, 20% or 50% of the turnout that voted Nazi, vigor and tireless effort characterized their commitment to the party. Without this commitment at the local level, any large-scale pan-German election effort for a Nazi ballot would not have been possible.

Inability to Grasp What Nazism Meant for Thalburg

Probably the most frequent criticism surrounding the Nazi controversy is the behavior of the German populace itself. It is unconscionable that the man who would start the largest war in human history, be the face of the genocide of 6 million people, and decimate Europe, could take power legitimately in Germany. Of course those who voted Nazi did not expect this to happen, but what exactly did they expect to happen? The answer is clear and confused at the same time: change, but change of what sort was purposely distorted.

Their most supportive aspect of society in Thalburg was the Burghers, and even they were unsure of what Nazism entailed. Allen discusses this point, saying,

The German middle classes hardly wanted a nihilistic dictatorship, but their ideological heritage from the days of Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm II left them ill prepared to appreciate what Nazism would mean or develop a viable alternative to it. (Allen, p. 100)

He goes on to say that the Nazis succeeded in being “all things to all men” and “In the face of mounting economic crisis, Thalburgers were willing to tolerate approaches that would have left them indignant or indifferent under other circumstances.” (Allen, p. 136, 276)

Problems With Allen’s Hypothesis

While Allen does a fantastic job recounting all of the electoral efforts on behalf of the Nazis, it remains fundamentally inexplicable how a very small party, despite all its vigor and ingenuity, could corner so much of the popular vote with an extremely conservative platform in a depression, when it would be the workers (traditional supporters of the left) who were most adversely affected by such a depression. Allen neglects to emphasize the roles that militarism and nationalism played in making the Nazi party attractive.

Second, there is the problem of the inability to recognize the Nazi threat to its electoral dominance and stop it. Maybe in Thalburg this was possible due to a general inability to conceptualize the problem correctly, but this is where using Thalburg as an example starts to fall apart. Although the SPD may have been ineffectual at the local level, it was not impotent nationally. It was clearly Hindenburg’s appointment of Hitler as chancellor, and Bruning/ von Papen’s precedents for abuse of power toward the Reichstag, not any Nazi electoral victory, which sealed the fate of Germany; not anything that happened in Thalburg.

Writing a book from this local point of view also leaves the impression that structurally, any vigorous and energetic party with an ambiguous platform could have mobilized many new voters and secured the kind of following that would make their leader attractive to the creators of a coalition government. The third problem then is in studying Thalburg, how much credit should one attribute to Hitler himself for the rise of Nazism? Allen says himself that local measures were key to establishing the totalitarian regime as national government. (Allen, 274) Leaving Hitler out of the picture and attributing everything to the uneasy reaction of a middle class to the chaos of depression does not seem to capture what Hitler actually represented to the nation, and therefore why it was the Nazis, and not the KPD or DVP or DNVP that captured power.

Conclusion

It can be extremely hard in a democratic system to separate the independent variables that result in election victory when tactics are so similar across parties, as is the case in late Weimar Germany. Allen doesn’t answer the question of how Germany could elect Hitler; he also doesn’t answer the question of why it was Hitler and not someone else equally fanatical and magnetic. But what he does do, and this is the reason this book is a success, is provide a clear outline of how vigorous local level politics can contribute more than any other factor to wide ranging national results. The lesson to be learned from The Experience of a Single German Town is that it is not the delusions of one mad man democratic nations must be on guard against, but the delusions we take to the polls ourselves when exercising the right to choose our leadership. |