Essay (back

to top)

“Is Murder Always a Crime?”

Nazi Doctors: A Secret Group of Mass Murderers

It is generally agreed that Hippocrates first composed what is know as the Hippocratic Oath in the 4th century B.C. From that century forward, as required in the terms of the Oath, any person admitted into the medical profession must pledge to uphold a prescribed standard of ethical practice. The underlying objective of this ancient oath was intended to prevent any caregiver from intentionally harming another human being in their care. However, on the ninth of October 1939, in spite of promising to “never do harm to anyone”, hundreds of German physicians broke their oath at the request of Adolf Hitler, also recognized by them as the Führer, the leader of the Nazi party (Wikipedia).

When Germany entered into World War II, the Nazi state had limited resources due to war debts incurred during and after the First World War. In order to support this new war effort, leaders within the Nazi regime now faced the task of alleviating what they considered the sources of monetary burden within the German economy. Therefore, they soon resolved that in order to alleviate one of these burdens, the following measure would be taken: the extermination of a group of people they termed “useless eaters” of the nation’s resources. This group included the mentally ill, physically handicapped, and the elderly. The regime believed that the care they received from the state on a day to day basis weakened the general welfare of the populace, as these groups received food and other state resources that would have been better spent on more valuable, better functioning members of society. To support this undertaking, on October 9, 1939, Hitler authorized a “professional system to exterminate the incurably ill” through a program of applied euthanasia, a scheme his party had promoted since the nineteen-twenties (Aly, 24). The Führer’s program, also known as “Operation T-4” (it was named after the office number and street name of its headquarters in Berlin on 4 Tiergartenstrasse), was directed by Hitler’s personal physician, Karl Brandt, and the Chancellery supervisor , Philipp Bouhler. These two principal administrators, along with a commission of “specialists”, were given the authority to select individuals living in state facilities to be euthanized. However, other officers who lacked the authority of the T-4 administrators soon expanded this program and took it into their own hands to determine who would live and who would die. As a result of this lack of oversight (when the program was briefly put on hold) it was estimated that by 1941, “Operation T-4” had far surpassed the sixty-five to seventy thousand deaths they had initially proposed.

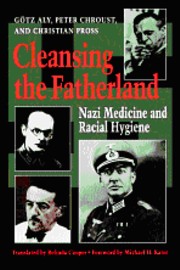

As Fred Mielke states, hundreds of medical professionals, including doctors and nurses, “took advantage of the cruel fate of defenseless individuals” in German occupied asylums and hospitals and used them for medical experiments (5). Furthermore, in addition to the corpses they were provided for experimentation, researchers signed off on the murder of thousands of living people for the same purpose. These medical men and women violated their oath to “never do harm” and performed numerous atrocities on thousands of defenseless adults, children and infants. However, Götz Aly asserts in Cleansing the Fatherland: Nazi Medicine and Racial Hygiene, that these gruesome and immoral crimes have been overshadowed by the genocide that took place throughout European cities and inside concentration camps during the holocaust -- even though many historians believe that such medical experimentation and programs of euthanasia set precedents for what was to occur later in the camps. However, as the well publicized post war exposure of the terror in these camps overshadowed earlier euthanasia programs, only a few of these doctors who participated in the euthanasia were actually brought to trial for their crimes. Consequently, there were countless numbers who participated without legal consequences. As Christian Pross describes in the introduction to Cleansing the Fatherland, “it was not only the tiny number of 350 black sheep among the German medical profession who were involved in medical crimes, but that many more were involved directly or indirectly, among them the cream of German medicine -- university professors and outstanding scientists and researchers” (5). Thus, despite the atrocities hundreds of “Nazi doctors” committed against humanity, and because their crimes were not well known, many went on to lead distinguished careers after the war, gaining prestige in their work and research performed during these years. Many used their “secret” status to profit monetarily from the situation.

Hermann Voss (1894-1987)

A disturbing illustration of this practice, which began at the beginning of World War II, allowed a racist anatomist named Hermann Voss (1894-1987) to transform his hatred for Poles, Jews, Communists and Slavs into a sort of homicidal rage that serves as an example of the lack of accountability for those doctors involved in the slaughter. A well published anatomist who began his carrier at the age of 19, Voss had accomplished many goals before he was asked to become a founder of the Reich University of Posen and take the position of dean at their Medical department. It was there that this doctor would begin his transition to heinous crimes against humanity. In his position as dean, Voss was able to “order” hundreds, perhaps even thousands of bodies to use in his experiments. However, many of these bodies never made it to his table as it seems that he was more interested in simply killing off the people he felt were ruining German society. For example, on 17 June 1941, he wrote in his diary, “Why aren’t a hundred Poles, or even more as far as I am concerned, killed for each murdered German?” (132). The following day he wrote, “Yesterday, two wagons full of Polish ashes were taken away. Outside my office, the robinias are blooming beautifully” (132). These dairy entries not only convey his hatred for those outside the “German race”, but they also show that he no longer considered them human beings. He even earned extra money by selling off their skeletal remains. Although Stefan Rozycki, an anatomy professor at the Reich University of Posen, found incriminating diary entries that attest to his brutality, Voss was not penalized. Even the publishing of his diary did not impede his career after the war, as the East German Council of State named him an “Outstanding People’s Scientist” for his so-called “contributions to the development of science in the service of peace” (102). Regardless of his behavior and mounting evidence, the murderer Hermann Voss maintained his status as “the most respected and influential anatomist in East Germany” for the rest of his career (102). Despite committing such atrocities, Hermann Voss was never charged with a single crime after the war.

Hermann Stieve (1886-1952)

Another example of this sort of brutality was gynecologist-anatomist Hermann Stieve (1886-1952), who, unlike Hermann Voss, did not choose his research subjects based on their supposed racial inferiority. According to Götz Aly, Stieve advocated the use of humans for experiments, enlisting the help of the staff at both the Ravensbrück concentration camp and the Plötzensee extermination site to not only choose his victims, but to kill them and then bring them back for postmortem examination. Stieve explained that this systematic approach allowed him “to observe the effects of highly agitated events on female sexual organs” and “investigate a large number of such cases” (148). However, Aly does not describe what kinds of experiments Stieve conducted. He simply stated that they were “experiments of the most repulsive kind” (148). After reading William Seidelman’s essay entitled “The Legacy of Academic Medicine and Human Exploitation in the Third Reich”, I found out that part of Stieve’s procedure was to have guards physically rape these women. Such methodology would imply a deep-seated hatred towards the opposite sex, not simply ambivalence towards race. However, this is not to say that his testing was not “of the most repulsive kind”. Considering the raping, testing and murder of these women, it is surprising to note that an essay referring to these torturous methods, written by Stieve himself, has yet to be criticized by any German official. Moreover, the Institute of Anatomy and Biological Anatomy at the University of Berlin found Stieve’s findings so significant, that they tested the conclusions found in “Influence of Fear and Psychological Excitement on the Construction and Functioning on Female Sexual Origins”. Once the validity of his research was proved, his theories soon became internationally accepted, so he, as others, profited from his criminal acts. Another example of this sort of brutality was gynecologist-anatomist Hermann Stieve (1886-1952), who, unlike Hermann Voss, did not choose his research subjects based on their supposed racial inferiority. According to Götz Aly, Stieve advocated the use of humans for experiments, enlisting the help of the staff at both the Ravensbrück concentration camp and the Plötzensee extermination site to not only choose his victims, but to kill them and then bring them back for postmortem examination. Stieve explained that this systematic approach allowed him “to observe the effects of highly agitated events on female sexual organs” and “investigate a large number of such cases” (148). However, Aly does not describe what kinds of experiments Stieve conducted. He simply stated that they were “experiments of the most repulsive kind” (148). After reading William Seidelman’s essay entitled “The Legacy of Academic Medicine and Human Exploitation in the Third Reich”, I found out that part of Stieve’s procedure was to have guards physically rape these women. Such methodology would imply a deep-seated hatred towards the opposite sex, not simply ambivalence towards race. However, this is not to say that his testing was not “of the most repulsive kind”. Considering the raping, testing and murder of these women, it is surprising to note that an essay referring to these torturous methods, written by Stieve himself, has yet to be criticized by any German official. Moreover, the Institute of Anatomy and Biological Anatomy at the University of Berlin found Stieve’s findings so significant, that they tested the conclusions found in “Influence of Fear and Psychological Excitement on the Construction and Functioning on Female Sexual Origins”. Once the validity of his research was proved, his theories soon became internationally accepted, so he, as others, profited from his criminal acts.

Conclusion

Although hundreds if not thousands of men and women escaped punishment after committing atrocious crimes under the Nazi regime, the efforts made by so-called “grass-roots” historians such as Götz Aly, Peter Chroust and Christian Pross have at least let these injustices come to surface. Without the commitment of such historians, hundreds of crimes committed in the Nazi era would have never been uncovered and publicized. Although it took almost fifty years from the end of the war for Nazi leaders to begin to die off, these men and women researchers were finally able to access records they never could have before. And, after painstakingly searching, they essentially found hundreds of documents that the Nazi party had not destroyed or “misplaced” that attest to the atrocities. So, even though many “Nazi doctors” escaped punishment and even profited from their crimes, Cleansing the Fatherland tells their story and marks them as vicious murderers, even if only in the mind of the reader. |

Another example of this sort of brutality was gynecologist-anatomist Hermann Stieve (1886-1952), who, unlike Hermann Voss, did not choose his research subjects based on their supposed racial inferiority. According to Götz Aly, Stieve advocated the use of humans for experiments, enlisting the help of the staff at both the Ravensbrück concentration camp and the Plötzensee extermination site to not only choose his victims, but to kill them and then bring them back for postmortem examination. Stieve explained that this systematic approach allowed him “to observe the effects of highly agitated events on female sexual organs” and “investigate a large number of such cases” (148). However, Aly does not describe what kinds of experiments Stieve conducted. He simply stated that they were “experiments of the most repulsive kind” (148). After reading William Seidelman’s essay entitled “The Legacy of Academic Medicine and Human Exploitation in the Third Reich”, I found out that part of Stieve’s procedure was to have guards physically rape these women. Such methodology would imply a deep-seated hatred towards the opposite sex, not simply ambivalence towards race. However, this is not to say that his testing was not “of the most repulsive kind”. Considering the raping, testing and murder of these women, it is surprising to note that an essay referring to these torturous methods, written by Stieve himself, has yet to be criticized by any German official. Moreover, the Institute of Anatomy and Biological Anatomy at the University of Berlin found Stieve’s findings so significant, that they tested the conclusions found in “Influence of Fear and Psychological Excitement on the Construction and Functioning on Female Sexual Origins”. Once the validity of his research was proved, his theories soon became internationally accepted, so he, as others, profited from his criminal acts.

Another example of this sort of brutality was gynecologist-anatomist Hermann Stieve (1886-1952), who, unlike Hermann Voss, did not choose his research subjects based on their supposed racial inferiority. According to Götz Aly, Stieve advocated the use of humans for experiments, enlisting the help of the staff at both the Ravensbrück concentration camp and the Plötzensee extermination site to not only choose his victims, but to kill them and then bring them back for postmortem examination. Stieve explained that this systematic approach allowed him “to observe the effects of highly agitated events on female sexual organs” and “investigate a large number of such cases” (148). However, Aly does not describe what kinds of experiments Stieve conducted. He simply stated that they were “experiments of the most repulsive kind” (148). After reading William Seidelman’s essay entitled “The Legacy of Academic Medicine and Human Exploitation in the Third Reich”, I found out that part of Stieve’s procedure was to have guards physically rape these women. Such methodology would imply a deep-seated hatred towards the opposite sex, not simply ambivalence towards race. However, this is not to say that his testing was not “of the most repulsive kind”. Considering the raping, testing and murder of these women, it is surprising to note that an essay referring to these torturous methods, written by Stieve himself, has yet to be criticized by any German official. Moreover, the Institute of Anatomy and Biological Anatomy at the University of Berlin found Stieve’s findings so significant, that they tested the conclusions found in “Influence of Fear and Psychological Excitement on the Construction and Functioning on Female Sexual Origins”. Once the validity of his research was proved, his theories soon became internationally accepted, so he, as others, profited from his criminal acts.