Essay (back

to top)

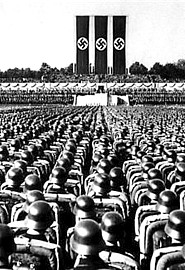

For history students today, it is easy to get the impression that the

German public was a unified mass that blindly followed Adolf Hitler’s policies

of antisemitism, terror, and total war. Videos and pictures often show

hundreds of thousands of Germans gathered at party rallies; seemingly,

most Germans adored Hitler and the policies he sought to institute. In

his book The Germans and the Final Solution: Public Opinion under Nazism,

David Bankier attempts to dispel this myth. Bankier makes an effective

argument that certain sectors of the German populace often disagreed with

Hitler and his policies, including antisemitic terrorism, and that at least

some portion of the German population was aware of the genocide occurring

in the east. His argument that Germans were generally apathetic and unwilling

to help Jews, however, is not as effective because he fails to distinguish

between various groups within society. Bankier relies on a multitude of

sources, including reports from the Gestapo and SA, personal diaries and

testimony, foreign intelligence, and radio broadcasts to compile a thorough

study of the German public’s opinions.

The first major issue that Bankier discusses is the contradictory nature

of the Nazi party itself. He correctly states that the Nazi regime was

based on “creating a situation in which the public would be permanently

mobilized” (Bankier, 14). However, the public did not understand how permanent

mobilization would lead to political stability – something that it craved

after the tumultuous Weimar Republic. Thus, Bankier argues, political fanaticism

and fervor for the party began to wane as early as the summer of 1934.

Bankier first examines the attitudes of the bourgeoisie. According to the

Gestapo in Trier, the number of people joining the party was dropping significantly

because “Hitler’s methods of repression and brutal terror” were dampening

enthusiasm for the party (Bankier, 17). In rural areas too, where Nazi

support was traditionally the highest, “political indoctrination bored

them” and despite the promises of agricultural reform, “the peasant population

continued to have reservations” (Bankier, 18). Bankier attributes this

political apathy to the difference between the promised agricultural reform

and actual industrialization that was taking place (Bankier, 18). Even

the industrial labor force started to have reservations about the Nazi

party. According to a Gestapo report from Munster, attendance of workers

at May Day celebrations was considerably lower than in 1934, as “’the public

mood has considerably deteriorated in recent weeks, particularly among

the local workers’” (Bankier, 19). As these reports demonstrate, not all

members of German society were completely captivated by the Fuhrer and

his new government.

Another area of German society that experienced decreased support for

the Nazi party was the SA itself. Once a strong political force, the SA

began to feel that Hitler’s policies, specifically the lack of antisemitic

action, marked a decrease in their importance. Bankier, based on a report

from the Aachen Gestapo, argues that “the organization’s low morale” resulted

in decreased participation in local branches (Bankier, 29). For example,

in Hanover, only twenty percent of registered activists consistently showed

up for duty (Bankier, 28). According to a report from the Wilhelmshaven

Gestapo, the SA also feared the army was going to replace it (Bankier,

31). Similarly, the Cologne Gestapo reported that local members of the

SA “were convinced that Hitler’s next step would be to dissolve the organization

altogether” (Bankier, 31). Thus, even one of the party’s main police branches

was experiencing political disillusionment in the early years of Nazi rule.

Bankier also argues that Hitler made foreign policy decisions when

confronted with the fact that the general public was becoming apathetic

towards party goals. According to Bankier, Hitler viewed “the major crisis”

in Germany not as a result of economic hardships, but the “unprecedented

political apathy, coupled with the conservative and clerical oppositionist

attitudes” in 1937 (Bankier, 48). In light of waning political support,

Hitler decided to remilitarize the Rhineland more than one year earlier

than planned (Bankier, 50). According to a diary entry from von Hassel,

German ambassador to Rome, Hitler’s “’chief motive in foreign policy is

internal policy,’” thus, Hitler decided to remilitarize the Rhineland in

order to restore national unity and pride (Bankier, 50). Bankier supports

his argument by correctly pointing out that the decision to remilitarize

was made in February 1936, the same month the Berlin Gestapo reported the

largest increase in general uneasiness surrounding Germany’s political

situation (Bankier, 52). Reports continued to come in from other regional

offices that certain sectors of the public were upset about the lifestyle

of party members, corruption within the party, and rumors that the army

was mounting a coup to take over the government (Bankier, 52). According

to these reports, Hitler was well aware of the political turmoil that was

brewing within his state – it was this knowledge that drove him to remilitarize

the Rhineland one year earlier. Thus, Bankier makes an effective argument

that political support continued to wane through 1936.

In the next section of his book, Bankier focuses on the issue of antisemitism

within Germany. Specifically, he seeks to understand how the German public

reacted to programs of antisemitism, and what impact those reactions had

on shaping Nazi policy. Bankier’s basic argument is that many people, despite

popular depictions, did not support antisemitic measures. As he shows,

however, the impetus to disagree with these measures did not come from

a general abhorrence of antisemitism, but rather from the terror, brutality,

and general nuisance it caused in the lives of German citizens. It is important

to remember here that Bankier’s argument is that public opinion under Nazism

was more diverse than traditional history may teach. He does not argue

that all members of certain classes disagreed with Nazi policy, nor does

he argue that all members of society were opposed to antisemitism. He does,

however, argue that it is impossible to evaluate public opinion during

the Third Reich if the public is assumed to be a homogeneous mass that

sought the same political, economic, and social goals.

One group of citizens to which Bankier plays particular attention is

the business class. He argues that antisemitic legislation and policies

were not popular because they upset the flow of business for both large

industrialists and small shop owners. Thus, there was an initial outcry

from businessmen in 1935 when the Nazis instituted a ban on Jewish shops.

Bankier correctly notes that they were aware that “antisemitic activities

damaged Germany’s economic interests,” fearing such policies would “hamper

their ties with traders abroad” (Bankier, 73). Other criticism came from

members of the tourist industry who felt that such policies made Germany

an undesirable travel destination (Bankier, 73). Businessmen also became

concerned with their own safety after events like Kristallnacht. Opposition

to Kristallnacht from the business class largely stemmed from fears that

“confiscation of Jewish property could be a precedent for plundering other

well-off sections of the public” as well (Bankier, 86). Other policies

that continued to bother businessmen included “government intervention

and bureaucratic control in the sphere of public enterprise” and a “noticeable

shortage of raw materials” for industrial production (Bankier, 97). A Gestapo

report from Rhineland – Westphalia indicates that many industrialists felt

antisemitic legislation was hindering economic growth and foreign trade

(Bankier, 98). Unemployment also became an issue of concern for industrialists,

as they too relied on Jewish workers and other businesses that employed

Jewish workers. The role that antisemitism played in hindering business

opportunities is just one way that Bankier shows not all Germans agreed

with Nazi policy.

Bankier also argues that some peasants and workers felt harmed by Nazi

antisemitic policy. Bankier argues that peasants, particularly those who

worked in agriculture, felt the removal of Jewish stock-dealers was harming

their business (Bankier, 96). A report from the Rhineland also comments

that stock-dealers preferred to do business with Jews because they were

better businessmen (Bankier, 96). Furthermore, a report from Pfalz indicates

that peasants deliberately disobeyed orders not to sell grapes to Jewish

winemakers, complaining that “the party did not provide any suitable alternative

to these traders” (Bankier, 96). Similarly, workers felt antisemitic policies

were preventing them from buying the cheapest available goods. A Gestapo

report from Dusseldorf claimed that “’when the worker is asked why doesn’t

he support small German enterprises, he answers that he goes wherever things

are sold cheap’” (Bankier, 93). Other reports indicate that workers felt

that if antisemitic policies continued to increase, the unemployment situation

would worsen (Bankier, 93). Bankier acknowledges that by no means does

the existence of workers and peasants who disagreed with antisemitism mean

that all members of these groups felt the same way about antisemitism.

The fact that at least some did not agree with antisemitic policies, however,

supports his argument that public opinion could be mixed.

Bankier next discusses the German public’s awareness and complicity

in the Holocaust. Through a number of different sources, Bankier shows

that at least large portions of the German public were aware of the Nazi

party’s role in the atrocities and genocide. First, Bankier runs through

a list of citizens who claim, either in testimony or through personal diaries,

that they suspected what was happening in the east (Bankier, 103). Furthermore,

a Gestapo report from Berlin in 1939 indicates that soldiers who returned

home on leave were spreading information about atrocities they saw first

hand in Poland (Bankier, 104). There are even reports from local agencies

that speak of church sermons that directly mentioned genocide, and how

“an anxious population began to seek some sort of spiritual comfort” after

learning of what was happening (Bankier, 105). Bankier also shows that

the German public was even aware of the method of genocide. For one, the

BBC launched a massive radio campaign at the end of 1942 to provide the

German public with accurate information on the extermination camps (Bankier,

113). This program included details that outlined gassing methods and cremation.

Even foreigners, such as the Spanish counselor Fermin Lopez Robertz, heard

rumors about the gas chambers; there was “’generally believed to be a certain

tunnel outside the city, where they were to be gassed’” (Bankier, 111).

As Bankier emphasizes, his use of the word generally indicates some broad

acceptance or knowledge of these facts. Bankier’s effective use of a variety

of sources make his argument compelling that at least a good portion of

the general public was aware of the events in the east.

The final part of Bankier’s book discusses the public’s reaction to

knowledge of the genocide. Bankier argues that, while many felt a sense

of shame over the atrocities, the general public’s unwillingness to help

signals the extent to which the public did not care about the problem.

Bankier dismisses accounts of helping Jews in need as “isolated expressions

of individual pity derived from various motives” (Bankier, 120). He also

claims that “as long as the Jews were ‘merely’ segregated and in most cases

not plainly perceived, the public could claim ignorance and deny the reality

created by the antisemitic policy (Bankier, 129). And, while some adults

“turned away, apparently in shame” over the sight of Jews being forced

to wear yellow badges, the constant exposure to such sights dulled their

sense of pity (Bankier, 123). Furthermore, Germans “relegated the Jewish

issue to a marginal position” because paying attention to it “entailed

an unpleasant awareness of the atrocities committed in the name of solving

the Jewish question” (Bankier, 146). While Bankier’s use of available data,

including SA reports, individual diaries, and testimony supports his claim,

he seems to be generalizing about the public too much in this discussion.

Rather than break down how individual groups felt about helping persecuted

Jews, Bankier comments on the public as a whole. He often resorts to talking

about “the Germans,” or “they” in order to make his point. Although Bankier

supports his claims with evidence, his argument on this particular subject

matter is simply not as convincing.

Critics of his book, like Robert Gellately, argue that Bankier’s argument

at the end of the book is not that strong. It is understandable why critics

feel this way. However, in his review published in the American Historical

Review, Gellately unfairly attacks the rest of the book. He comments that

Bankier’s “grand synthesis” and rejection of “in-depth social analysis”

make his argument ineffective. Furthermore, Gellately claims that Bankier

contradicts himself because he describes the “uphill battle” of convincing

the population to believe in antisemitism, while simultaneously arguing

that Germans tended to be antisemitic by nature. Firstly, Gellately’s comments

on synthesis are unfair. It is nearly impossible to complete a social study

and have it apply universally to the subject group, which is why Bankier

speaks of specific groups within German society: the SA, peasants,

workers, and businessmen. Furthermore, Bankier is not trying to argue that

all of German society felt antisemitism was wrong, rather, he argues that

certain groups of people did not adopt antisemitic policies with as much

fervor as propaganda or post-war reconstructions often depict. Gellately’s

comments regarding the contradiction between the struggle to implant antisemitism

and German’s antisemitic nature are also wrong. Bankier does not argue

that Germans were antisemitic. Instead, he argues that Nazi policies of

discrimination on the basis of antisemitism were often unwelcomed because

they disrupted daily life. Thus, antisemitic policies were often unwelcomed

because of this disruptive effect, not because Germans were antisemitic.

Gellately fails to see this distinction, which is why his comments are

inaccurate.

Bankier’s book The Germans and the Final Solution: Public Opinion

under Nazism successfully points out that German public opinion during

the Third Reich was more varied than conventional wisdom may indicate.

His discussion of general apathy towards the party and its goals and the

backlash against antisemitic violence proves that German society was in

fact not as brainwashed as many once thought. His work constitutes an invaluable

source of information regarding public opinion under the Third Reich, as

it breaks the stereotype that the German public was a homogeneous mass

willing to support the Nazi cause at all costs.

|