Essay (back

to top)

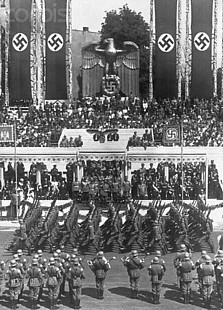

Despite ending over a half century ago with its total destruction, the

Wehrmacht continues to draw debate on its position within the Third Reich.

In his book Hitler’s Army Omar Bartov attempts to address the degree to

which the Wehrmacht was a highly professional military organization carrying

out orders, or an extremely politicized army motivated by widespread National

Socialist ideals. Bartov uses four distinct yet related theses to contest

the idea that the Wehrmacht was detached from Hitler’s political aims and

acting independently from its Nazi masters. His work provides evidence

that the Wehrmacht truly became Hitler’s army through German soldiers’

war experience, social organization, motivation, and perception of reality;

especially on the eastern Front. Drawing on an extensive collection of

Wehrmacht documents and letters from German soldiers, Bartov proposes that

the soldiers’ perception and experience throughout the war was in fact

impacted by Nazi ideology. His argument highlights the profound demodernization

the Wehrmacht suffered on the eastern front along with the destruction

of “primary groups”. This resulted in the leadership compensating by intensifying

the troops political indoctrination to sustain cohesion and motivation.

Combined with the harsh discipline, acceptance of war crimes, adoration

of Hitler, and the extent of pre-military indoctrination distorting soldiers’

perception of reality, Bartov explains the success Nazi propaganda had

influencing the Wehrmacht. Bartov’s four theses together provide persuasive

and concrete evidence confirming that during the war the Wehrmacht was

not independent of the Nazi regime but rather truly Hitler’s army in both

its actions and beliefs.

Bartov begins by pointing out the contradiction between the notions

that the Wehrmacht was a powerful modern army, and the intense demodernization

it suffered particularly on the Eastern Front. With the huge success of

the Blitzkrieg campaigns on the western front, the Reich used the same

technique when it invaded the Soviet Union. Unfortunately the Reich’s Blitzkrieg

tactics and strategies, along with limitations of production capacity due

to not totally mobilizing the Reich’s economy, proved to be devastating.

It led to a vast majority of the Ostheer (eastern army) living and fighting

in primitive conditions. In an effort to adequately supply the war the

overall production of tanks, weapons, and transportation was increased

significantly. This promoted the view of modernization within the Wehrmacht;

however, the experience of most ground troops was that of demodernization,

returning to trench warfare at times (Bartov, 16). The eastern front soldiers

had a vast expanse of territory to cover and were exposed to the harsh

winters of Russia. Heavy fighting and poor weather conditions continued

to diminish the number of tanks and trucks forcing troops to halt their

advance. Thus the demodernization resulted in “throughout the front lack

of fighting machines combined with the climatic and geographical peculiarities

of Russia to deprive this former Blitzkrieg army of all semblance of modernity”

(Bartov, 18). By early September the Wehrmacht had lost almost two-thirds

of its tanks on the Eastern front forcing them to rely on horse-drawn wagons

and declare itself “incapable of conducting mobile warfare” (Bartov, 20).

With its material strength and manpower dwindling, the entrenched Wehrmacht

soldiers began showing symptoms of “mental attrition caused by fatigue,

hunger, exposure, diseases, and anxiety” (Bartov, 22). Soldiers faced new

aspects of this harsh war constantly with no accommodation against the

elements; the troops spent both day and night exposed in the open. By 1942

two-thirds of the overall 214,000 casualties were victims of illness and

frostbite, as opposed to enemy action. These elements not only materially

demodernized the Ostheer but brought about a change in mentality; soldiers

gained the instinct of self-preservation. One soldier wrote, “Here war

is pursued in its pure form, any sign of humanity seems to have disappeared

from deeds, hearts, and minds” (Bartov 26). This could be the reason behind

the willingness of the men fighting on the eastern front to make the ultimate

sacrifice, they refused to give up. There was a disordered element in this

new mentality in which troops welcomed death and returned to savagery.

Additionally, “The demodernization of the front consequently greatly enhanced

the brutalization of the troops, and made the soldiers more receptive to

ideological indoctrination and more willing to implement the policies it

advocated” (Bartov, 28). This process of demodernization of the front had

many significant penalties, one of which was the destruction of “primary

groups”. Primary Groups derive from a theory believing that the social

organization of the Wehrmacht, in which troops were organized into a specific

unit from the same conscription zone, would allow men to forge “primary

groups” making ideology needless.

In the second chapter Bartov seeks to discredit the commonly held conception

that “primary groups” were the social units providing the cohesion of the

Wehrmacht. Formulated in 1948 by Shils and Janowitz, the “primary group”

theory suggested,

The cohesion of the Wehrmacht was thus said to have been the product

not of abstract ideas, but of a concrete and clearly identifiable social

system which catered to the formation and preservation of close personal

ties between soldiers within a network of “primary groups” (Bartov 31).

This theory maintains that social organization made ideology unnecessary,

asserting that the outstanding fighting power of the German army rested

on its organization. Bartov challenges this popular theory by insisting

that the Wehrmacht constant loss of life at the front line destroyed these

“primary groups”, and instead ideology provided the cohesion and will to

continue fighting.

Bartov focuses on the tremendous loss of life suffered by the Wehrmacht

to weaken the argument for “primary group” ties. The invasion of the Soviet

Union consisted of 142 division representing 3,050,000 men (Bartov 36).

By September almost all of the divisions were reporting upwards of 50 percent

declines in their initial battle strength, and by November the high command

had exhausted all of its reserves. Bartov questions how primary groups

could survive in the midst of these tremendous losses. In order to compensate

for these tremendous losses the Wehrmacht had a replacement system which

attempted to follow the primary group structure. However, this soon became

impossible when front-line formations began to diminish rapidly; in the

rush to reinforce them there was no time for consideration of “primary

group” ties. With this constant turnover rate within formations Bartov

concludes that most soldiers had little “opportunity of forming stable

primary groups, many of them hardly spent more than a few days in its ranks

before they were either killed or sent back to the rear in hospital trains”

(Bartov, 49). Bartov effectively refutes the “primary group” theory by

pointing out the massive casualties and rapid manpower turnover rate, leaving

ideology as the factor behind the Wehrmacht social organization.

Harsh military discipline and obedience had a long tradition in Germany

however with the unique circumstances on the eastern front discipline took

a new form. Commanders turned to draconian punishment to instill into the

troops fear of noncompliance. Fearful of their commanders and the enemy,

troops turned against civilians and prisoners. Legalization of crimes,

which became commonplace within the Nazi regime, soon permeated the ranks

of the Wehrmacht. “Soldiers were ordered to commit official and organized

acts of murder and destruction against enemy civilians, POW’s, and property;”

actions such as these were rarely punished (Bartov, 61). This perversion

of discipline raised the level of barbarism, which in turn further brutalized

discipline. The army did not merely turn a blind eye towards the criminal

actions of the regime, and it ordered its troops to carry them out (Bartov,

70). This was in part because the army’s propaganda represented all Russians

as Untermenschen, people not deserving of life. By legalizing murder, torture,

robbery and destruction within a highly ideological context, controlling

troops became difficult.

Following this new found acceptance of crimes, Bartov focuses on how

the Ostheer became the target of harsher policies concerning punishment

for breaches of discipline regarding combat activity. By allowing troops

to get away with breaches of discipline in regards to treatment of POWs

and civilians, it became possible for the officers to enforce harsh combat

discipline to maintain the cohesion of the army. Bartov highlights this

fact by explaining that between 13,000 and 15,000 German soldiers were

put to death by their own army mostly based upon ideological political

grounds (Bartov, 96). The eastern front’s discipline was achieved through

fear of execution if a soldier neglected his duties, such as by desertion

or self-inflicted wounds. This was reinforced within an order from Hitler,

“Every commanding officer…will enforce the execution of orders, if necessary

by the force of arms, and will immediately open fire in case of insubordination”

(Bartov, 100). This vicious circle of brutality confirmed that the Nazi

view of war had been positively established within the Wehrmacht and “remolded

its conception of legality and criminality, morality and justice, discipline

and obedience” (Bartov, 95).The Ostheer was therefore held together by

a combination of harsh combat discipline and general license to barbarism

towards the enemy rather than “primary groups.” Both of these elements

became a central component of the Wehrmacht’s determination to fight, and

provided an ideological cohesion which played a crucial role in the prevention

of disintegration of the army.

With his three previous theses thoroughly explained, Bartov moves on

to discuss the extent to which years of pre-military and army indoctrination

distorted the soldiers’ perception of reality. By using personal memoirs

from soldiers regarding their experience within the Hitler Youth to generals

who fought on the eastern front, Bartov is able to portray the Werhmacht’s

extreme deification of the Fuhrer. A majority of the fighting men in the

Third Reich spent a considerable amount of their youth under National Socialism.

The regime realized the potential in indoctrinating Germany’s youth at

a highly impressionable age and consequently won them over by entrusting

them with tremendous destructive powers (Bartov, 110). The degree to which

Nazi ideology, put forth by the HJ, molded the youth’s minds is evident

in soldier Dieter Borkowski’s memoir; when he heard of Hitler’s suicide

he stated, “These words make me feel sick, as if I would have to vomit.

I think that my life has no sense any more” (Bartov, 110). As the youth

movement began to adopt Hitler’s vision, the army also began to introduce

indoctrination to the troops.

The indoctrination of the troops had two significant roles, First it

taught the troops to trust and believe in Hitler’s political and military

wisdom without doubt, and second it provided the soldiers with an image

of the enemy so distorted that they were able to justify their actions.

“Belief” in Hitler became a central element in Nazi ideology; in order

to promote this the Wehrmacht’s propaganda associated Hitler with God to

present his mission as emanating from a divine will (Bartov, 120). To ensure

the troops would receive the appropriate political instructions, educational

officers were introduced to reaffirm that their enemy was “the embodiment

of the Satanic and insane hatred against the whole of noble humanity” (Bartov,

126). By dehumanizing the enemy, the Wehrmacht was able to justify its

atrocities; an NCO described the Russians as “no longer human beings, but

wild hordes and beasts” (Bartov, 158). By addressing contrasting theories

Bartov effectively dismisses the opposing view that Nazi ideology did not

permeate into the Wehrmacht and proves Nazi indoctrination did in fact

did have a major impact. The distorted perception of reality amongst the

ranks of the Wehrmacht in the latter stages of the war proved to be a causal

factor in maintaining the cohesion of the army.

Despite providing ample evidence to support his theses, several opponents

question Bartov’s argument. In The Journal of Modern History’s review

R. J. Overy questions whether German soldiers’ responses were due to indoctrination

or the pressures of the environment, such as trekking across destroyed

landscape and being subjected to partisan violence. He believes that behaviors

of other armies in similarly harsh conditions need to be compared to confirm

Bartov’s theses.

In conclusion, Bartov proves his theses that combined the demodernization

of the front, destruction of “primary groups”, perversion of discipline,

and distortion of reality truly molded the Wehrmacht into Hitler’s army.

The vivid accounts of soldiers’ and commanders’ experiences portray the

Wehrmacht’s development throughout the war and sheds light on its exact

role within the regime. I strongly believe that with the support of Bartov’s

material evidence, historians should not place the Wehrmacht in a separate

category when addressing the appalling crimes committed by the Nazis; rather

described as a primary component to Hitler’s Weltanschauung.

|