Essay

(back to top) From 1939 to 1945 the Nazis

nefariously went through the process of murdering some 200,000 mentally

ill and physically disabled people whom they had labeled “life unworthy

of life.” The systematic murder of these people was known as the “euthanasia”

program. Michael Burleigh examines and exposes in full, grim detail the

workings of this program in his book Death and Deliverance: ‘Euthanasia’

in Germany 1900-1945. Burleigh pays special attention to the role played

by all parties involved in the covert and complex series of operations

that defined the euthanasia program--from the nurses, doctors, and Nazi

officials who facilitated the process, to the patients themselves. Through

extensive research into archival material, such as patient-relative letters

of correspondence, asylum reports and medical files, interviews with former

staff, and court documentation from the post-war trials, Burleigh shines

light on the relationship between psychiatric reform, eugenics, and government

cost-cutting policies during the Weimar Republic and Nazi periods.

Looking further, Burleigh seeks to explore the role ‘ordinary’ individuals

played in this process. Why were ‘ordinary’ people--agricultural laborers,

builders, cooks, etc.--willing to look past individual rights and concern

for the weak in favor of a strong Nazi party with its collectivist goals

such as the good of the race, economy and nation? Burleigh questions how

far silent collusion went in facilitating the murders, and asks whether

public acceptance of the ‘euthanasia’ program could have expedited the

process (Burleigh, 4).

Through a close and compelling examination of all those involved in

the euthanasia program--his attention to the victims is particularly fascinating

and rich in detail--readers are left with a fuller understanding of how

a nation could allow for the murder of over 200,000 mentally ill and physically

disabled people. By personalizing the stories of the victims, Burleigh

allows them to take a real form in the minds of historians and readers

alike, rather than leaving them to become simple statistics.

Ultimately troubled by a failing economy, and susceptible to propaganda

that labeled these patients as “life unworthy of life,” many Germans were

willing to accept, if not partake in, the murder of psychiatric patients

for the betterment of their own as well as their nation's financial standing.

And while there were those who spoke out against the program--Catholics

who believed in the sanctity and value of all life were particularly troubled

and eventually vocal in their rebuke--the euthanasia program continued

on in its murderous course.

Coming to Embrace Euthanasia

At the conclusion of World War I, Germany was in economic disarray.

With people starving in the streets, many German professionals began mulling

over different ways to alleviate the economy. Budget cuts were a main topic

of discussion, and as Burleigh explains in the first section of his book,

psychiatrists were deeply concerned over their expenses. Echoing the sentiments

of many psychiatrists in the early part of the 1920s was Robert Gaupp,

who felt wrong caring for “his patients, when people of ‘full value’ were

starving to death in the world outside” (Burleigh, 20). It was in this

period that the concept of the “destruction of life unworthy of life” came

into existence, the term being coined in 1920 by authors Karl Binding and

Alfred Hoche (Burleigh, 16). Writing in favor of involuntary euthanasia,

Binding and Hoche found an audience with those who like themselves saw

the mentally ill as a burden on German society.

As inflation rose and the economy continued to suffer in the early

1920s, asylums for the mentally ill began to close. Expenditure was cut

in favor of areas of medicine where cures could be expected or where it

seemed likely that a patient could be sent back into the work force (Burleigh,

25). Despite cuts in funding, the number of patients admitted to asylums

rose steadily between 1924 and 1929 (Burleigh, 29). With more patients

came added responsibility and a need to use more resources. This did not

sit well with those in the Binding and Hoche camp. With the economy still

floundering by the turn of the decade, a new sense of urgency arose in

the psychiatric field, leaving several psychiatrists to discuss ideas of

eugenic sterilization (Burleigh, 37). By 1932, eugenic sterilization had

found popular support in Germany, leading the way for the signing of the

Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseased Progeny on 14 July 1933 (Burleigh,

42). Involuntary sterilization was now legal. In the coming years, as the

Nazi Party took control over the nation, the idea of killing the mentally

ill would be discussed by senior officials responsible for the administration

of Germany’s asylums (Burleigh, 47).

From Sterilization to Murder

Segueing into the Nazi period, Burleigh describes the introduction

of the “Fuhrer principle,” under which asylums began to take new shape

and find new personnel (Burleigh, 50). Non-Nazi doctors and nurses were

replaced with SS doctors who were more willing than most to use drugs to

kill patients (Burleigh, 53). As qualified personnel were replaced with

unqualified members of the National Socialist party, asylums were losing

those who had any concern for the sick. In turn, life inside the asylums

became increasingly distressful for the patients. Then, in August of 1939,

the Reich Committee made it mandatory for doctors and midwives to register

all “'malformed’ newborn children” (Burleigh, 99). These children’s paperwork

were to be examined by a team of “expert referees” who would determine

whether or not each child should live or be killed (Burleigh, 101).

Readers can see both the bureaucratic process at work--one that is

so indicative of Nazi Germany--as well as the large number of people involved

in the early stages of the euthanasia program. Although the team of “referees”

was ultimately responsible for the killing of the children, these men based

their decisions on the registration forms that were filled out by midwives

and nurses. Burleigh is interested in every person involved in this program,

and thus convincingly highlights the role each person played, be it a midwife,

a senior doctor, or Hitler himself. Of even greater concern to Burleigh,

however, is the way in which the program’s participants dealt with the

reality of their murderous job. Using nurses at the pediatric clinics as

an example, Burleigh describes the mixed emotions that came with the job:

Although they sometimes requested transfers, and undoubtedly found

the work disturbing, nonetheless they also regarded it as necessary to

‘release’ the ‘regrettable creatures’ in their care from their suffering.

(Burleigh, 105)

Perhaps what tension did exist arose due to the fact that these nurses

were assisting in the murder of children. Or maybe the nurses involved

had some understanding of humanity. If it was difficult for some nurses

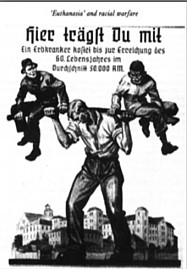

to accept their “active,” role in the euthanasia program, Nazi propaganda

that began before any patients were killed made it was far easier for the

German public to later view the killings as beneficial to their nation.

Films like “Victim of the Past,” released in 1937, painted psychiatric

patients as a severe burden to Germany. Under Hitler’s orders, “Victim”

was played in all German theaters, and warned of an “endless column of

horror” that would infiltrate German society if the disabled were not dealt

with (Burleigh, 191). These films were not only used to develop in Germans

a “moral void,” but were also used by the organizers of Aktion T-4 to “induct

their subordinates into the process of mass killing” (Burleigh, 195). Once

Germany proceeded to a wartime economy in 1939, this “endless column of

horror,” quickly became not only a threat to the German race, but also

a detriment to the economy.

Meanwhile, the planned adult euthanasia program was labeled “Aktion

T-4” and was put in place as specified in Hitler's secret memo dated September

1, 1939 (Burleigh, 112). With markedly angry undertones, Burleigh describes

the “ordinary” people who worked for T-4 as brutal and insensitive working-class

males, who would party and drink around dead corpses (Burleigh 127).

One of these men whom Burleigh highlights is Kurt Eimann, whose utter

commitment to the SS and total ruthlessness afforded him the ability to

do whatever was asked of him: which in this case was the systematic murdering

of over three thousand Polish psychiatric patients (Burleigh, 132). It

is instances such as this one, where Burleigh’s tone becomes increasingly--albeit

understandably--angry, that it becomes compelling to evaluate the criticisms

of Michael Kater, of York University. Writing in the American Historical

Review, Kater challenges Burleigh's position on these “ordinary” men and

women, and challenges Burleigh over what he sees as the author’s “blanket

treatment of ‘euthanasia’ killers as deranged or marginal people” (Kater,

865). Though, Kater’s belief that Burleigh depicts these “ordinary” people

as marginal is completely misguided. While Burleigh offers more in depth

insight into the lives of individual, “ordinary,” victims, he is equally

interested in the minds of the perpetrators and their motivations. At the

same time, knowing that an otherwise ordinary laborer such as Eimann could

go on to be responsible for the killing of three thousand innocent people,

makes it difficult for readers to sympathize in any way with these “ordinary”

members of German society and the devastating role they played in the euthanasia

program.

A Killing Apparatus

Once the T-4 program was conceived, its workings had to be established.

Everything became embedded in the bureaucratic process as personnel had

to be trained in the killing of thousands of people and ties had to be

created between asylum officials--who were responsible for releasing patients

to their death--and the T-4 doctors who would proceed with the actual murder.

The doctors who turned the valves to the gas chambers showed no signs of

concern for the victims (Burleigh, 134). But, before the valves could be

turned, T-4 personnel had to make sure the asylum authorities were complicit

in regards to the program. Authorities knew the patients they handed over

to the T-4 personnel were being sent to their death, and in response, a

certain number of them attempted to resist cooperation (Burleigh, 142).

However, the clearing out of the asylums was ultimately inevitable, and

Burleigh’s description of men and women being dragged from asylums to their

certain deaths is chilling (Burleigh, 142).

The psychiatric patients could find no refuge in the institutions,

but with thousands being killed, what response, if any, was there by the

relatives of these victims? Burleigh describes the response as being mixed,

as some relatives felt deeply saddened, while others welcomed the death

of those who were otherwise a financial burden (Burleigh, 143). Here the

idea of psychiatric patients as an unwanted cost comes back into play,

which is important given its link to Burleigh’s thesis. As mentioned above,

many Germans in the Weimar Republic worried that psychiatric patients were

a financial burden to the state. Dr. Bodo Gorgass, a chief doctor among

the T-4 personnel, went on record in 1947 reasoning that mentally ill people

were a financial burden to their relatives and that the state should make

the decision to kill for them (Burleigh, 152). This reasoning would seem

outlandish had Burleigh not made it clear that some relatives did in fact

accept the murders as a cost effective process. Burleigh in no way suggests

that these sentiments were universal. However, by presenting them, readers

can better gauge his assertion that economics played a crucial role in

the development and implementation of the euthanasia program.

Reactions Against and an End to Euthanasia

While immense measures were taken to keep T-4’s operations covert--Burleigh

describes the euthanasia program as one of “mass murder by stealth”--it

was nevertheless impossible to hide from the public the murdering of hundreds

of thousands of people (Burleigh, 162). With asylums constantly emptying

in early 1941, community members were well aware of what was going on,

leading many to openly express their anger towards a state that was now

in “such a deleterious condition that it was having to kill the handicapped

to fund its war effort” (Burleigh, 163). Families of victims who did accept

the fate of their relatives also spoke out against the euthanasia program,

placing insinuating death notices in local papers that exposed the public

to the grim nature of the program (Burleigh, 165). The Catholic Church,

which had been silent throughout the early stages of the euthanasia program,

began limited protests in August 1941, despite the fact that--as Burleigh

explicitly mentions--70,000 people had already been murdered (Burleigh,

173).

The timing of the Church’s response seems highly questionable, if not

inexcusable, yet the actions of a few individuals within the Church cannot

be ignored. Specifically, Burleigh introduces the bishop Clemens August

Graf von Galen, who in August 1941 gave a damning indictment of the Nazis’

euthanasia program (Burleigh, 178). Galen’s sermon was a direct attack

on the euthanasia program, the effects of which left Hitler and the Nazi

authorities incensed. The Aktion T-4 would be halted soon after Galen’s

sermon, making it appear that the Church’s response played a role in suppressing

murder. However, Burleigh argues that by the summer of 1941, another, more

important motivational factor was at hand:

The euthanasia programme was not halted because of some local difficulties

with a handful of bishops, but because its team of practiced murderers

was needed to carry out the infinitely vaster enormity in the East that

the regime’s leaders were actively considering. (Burleigh, 180)

It was now time for the expertise and technical skills which were developed

in Aktion T-4 to be put to use against Hitler’s primary enemy: the Jews.

In this book, Michael Burleigh does an excellent job of presenting

a subject that is as profoundly disturbing as it is rich in historical

evidence. From the start, Burleigh establishes the questions he hopes to

resolve and proceeds like a skilled tactician to evaluate and procure the

answers he set out to find. His examination of the role economics played

in allowing for a manipulative propaganda campaign, as well as the weakening

of the minds of those involved in the euthanasia program--the majority

of whom believed that what they were doing was beneficial to Germany--is

chilling. His description of the relative ease with which many of the men

and women responsible for these murders came back into German society after

the war--Eimann for example, who oversaw the death of at least 3,000 people

was sentenced to merely four years in jail--is as sobering as it is infuriating.

Finally, Burleigh’s assertion that the technical expertise acquired in

the euthanasia program “would eventually be brought to bear on annihilating

the Jewish population of occupied Europe” (Burleigh, 133) is immensely

significant in that it contributes to a better, fuller understanding of

the Holocaust and its evolution. |