Essay (back

to top)

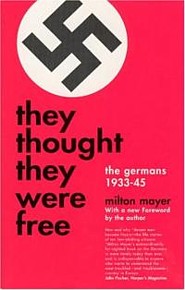

Students studying German history in the pre-WWII period often ask themselves

the difficult question: What would I have done? Milton Mayer, author of

They Thought They Were Free: The Germans 1933-1945, examines the

lives of ten Nazis, people who actually faced this question. Mayer, an

American journalist of Jewish and German descent, moved to the small town

of Kronenberg, Germany. In Kronenberg, he met, interviewed, and got to

know ten Nazi men. Mayer readily admits that he expected to hate the Nazi

men he spoke with, but was shocked to discover that he liked them and even

came to regard them as his friends. The ten men Mayer interviewed were

not "men of distinction" or "men of influence," they

were common men in a nation of around seventy million (Mayer, 45). Through

these interviews, Mayer hoped to gain insight into the lives of these Nazi

men and the German people as a whole. He hoped to be able to pass along

this knowledge to the American people so that they would have a better

understanding of what life was truly like for the 'average' German person

in 1933 to 1945. By examining the men's reasons for joining the Nazi

party, why they chose not to resist, and how they reflect back on Nazism,

Mayer convincingly demonstrates that while the German people did have a

unique poltical culture and history that enabled the rise of Nazism, the

Nazi movement or one like it could happen anywhere or to any people.

Mayer explores the reasons why his ten Nazi friends joined the Nazi

movement. and persuasively concludes that most joined for practical reasons.

Many of the men decided to join the Nazi party because it was the easy

thing to do. Heinrich Hildebrandt, a high school teacher, made the decision

to become a Nazi because it made work easier. Hildebrandt, who had been

an active member of the old Democratic Party in 1930, found that joining

the Nazi party made him stand out less. Once in the party, he was in less

danger than if he had decided not to join. While some joined the Nazis

to remain anonymous, many joined for purely economic reasons. Many Germans

struggled in the fiscally tough times of the 1920s and 1930s, Johann Kessler,

a labor front inspector, was one of these men. Kessler joined the party

because he desperately wanted and needed a job. Similarly, Herr Wedekind,

a baker, joined National Socialism because he thought it solved the unemployment

problem. The other men Mayer interviewed included: Karl-Heinz Schwenke,

Gustav Schwenke, Carl Klingelhofer, Heinrich Damm, Horstmar Rupprecht,

Hans Simon, and Willy Hofmeister. Men like these joined the Nazi party

for practical reasons, such as to improve their economic status.

Mayer discovers some of the other reasons his Nazi friends were drawn

to the party. In such desperate times, Mayer's Nazi friends went to hear

someone talk about something inspiring, a new and better Germany. Hitler

talked to the German people, railed against the failing Weimar democracy,

the Versailles peace treaty, and unemployment. Mayer's friends hated politicians,

the parliamentary system, and the current government. National Socialism

was also viewed as a defense against the Communist Party. All ten of Mayer's

Nazis describe Nazism as a way to combat the rise of Communism. One man

describes Bolshevism as "the death of the soul" (Mayer, 97).

He goes on to explain the feeling that, during this time, Nazism was the

only choice other than Communism. The men discuss Nazism as a positive

thing for Germany. In such hard times, the Nazi party cared for the German

people and their needs. All ten of the men discuss how Nazism restored

social services and helped the German people. Herr Kessler describes the

way the party helped with everything from domestic problems to religious

matters to housing problems. He explains: "No organization had ever

done this before in Germany…such an organization is irresistible to men.

No one in Germany was alone in his troubles" (Mayer, 222). Mayer also

notes that almost all of the men often refer to themselves as, "wir

kleine Leute, we little people" (Mayer, 44). National Socialism was

viewed as an organization that broke down class distinctions. Under Nazism,

"little men" felt important and not inferior to intellectuals

who, by 1933, were looked upon as untrustworthy and unreliable by the Nazis

(Mayer, 112). Mayer provides the reader with a good sense of why other

'ordinary' men were drawn to the Nazi organization.

Mayer convincingly draws some broad conclusions about the German people,

German history, and German culture that could have also influenced 'ordinary'

men like his ten friends to join the Nazi movement. After spending an extended

period of time in Germany and among its people, Mayer admitts that he believes

that there is something uniquely different about the Germans. Because of

its geographic location, Germany is surrounded by other European countries

and has a history of being invaded. This history has led to a very real

or imaginary sense of external pressure on the German people. The author

states: "What the rest of the world knows as German aggression the

Germans know as their struggle for liberation" (Mayer, 251). The author

admitts that this pressure may be real or imaginary, but that it ultimately

does not matter because the German people believe the pressure to be real.

He concludes that German history is different from the American experience.

Mayer argues that the concept of any citizen as a potential ruler does

not exist in Germany. The author writes: "The concept that the citizen

might become the actual Head of the State has no reality for my friends"

(Mayer, 159). Mayer provides some sound insight into German history and

its political culture that contributed to the success of Nazism in the

1930s and 1940s.

Mayer investigates why none of the ten Nazis resisted and how, as a

result of the lack of German resistance, the Nazi party came to be responsible

for the death of millions of Europeans. The author fails in one aspect

because he does not address any specific cases in which Germans did engage

in active resistance to their government. Despite this lack of acknowledgment,

Mayer does make some great arguements about why the 'average' German did

not resist. Mayer comes to an understanding that the real community had

very little to do with Hitler and the State. The author believes that real

people were concerned with their day to day business and that the State

did not come into direct contact with the average person's life very often.

Mayer provides readers with an intelligent explanation on why the majority

of German people did not put forth any type of resistance to Hitler and

Nazism. One explanation the author supplies is the idea that Nazism was

not an overnight transformation. Rather, it was a gradual process that

occurred little by little, step by step. He explains: "Step C is not

so much worse than Step B, and, if you did not make a stand at Step B,

why should you at Step C? And so on to Step D" (Mayer, 170-171). All

of the small steps built up gradually, and as many of the men explain to

Mayer, it was not them who were personally in danger. In many of the interviews,

the Nazi men convey an "it wasn't me" attitude. One man explained

to Mayer how when the Communists were attacked, he was not a Communist,

so he did nothing; and then when the Gypsies were attacked he again did

nothing because he was not a Gypsie; and then finally when the Jews were

attacked he yet again did nothing because he was simply not a Jew (Mayer,

169). From stories like this, Mayer concludes that this attitude greatly

contributed to the lack of German resistance to Nazism. The author also

points out that German society was already stratified into Jews and non-Jews.

Not one of the ten Nazis had ever known a Jewish person intimately. People

are less likely to do something for someone else, or put their own lives

or jobs at risk, for someone they do not even know personally. Most of

Mayer's interviews illustrate that most Nazis were antisemitic for economic

reasons. In one interview, Herr Hildebrandt explained to Mayer how him

and his wife moved into the home of a Jewish family after they had been

deported. Although Hildebrandt expressed some feelings of shame and embarrassment,

he justified the act because his wife was pregnant and housing at the time

was in very short supply. Through examples such as Hildebrandt's and one's

similar to his experience, Mayer concludes that 'average' Germans did not

resist because they were not personally being affected by the Nazi regime

and in many cases stood to benefit from their silence.

After his year in Germany, Mayer draws some insightful conclusions

about how his ten Nazi friends reflect upon the Nazi movement. Almost all

of his ten friends still talked about Nazism in a positive light. Herr

Kessler openly admits that while he regards National Socialism as a bad

thing for him personally because he "lost his soul," overall

it was good for Germany (Mayer, 209). Most of Mayer's Nazi friends shared

a similar sentiment to Kessler's. None of the men expressed feeling any

extreme guilt about the Holocaust, and on multiple occasions some of the

Nazi men Mayer talks to alluded that they are not fully convinced that

the Holocaust actually happened. Mayer seems frustrated when he writes:

"Nobody has proven to my friends that the Nazis were wrong about the

Jews. Nobody can" (Mayer, 142). Mayer expresses a sense of annoyance

when talking about the concept of shame and guilt with the ten Nazi men.

In the end, Mayer's friends thought of themselves as "little men"

and as a result were not convinced of their own personal guilt.Mayer is

disheartened by the German people's lack of collective shame. He lements:

"Shame is a state of being, guilt a juridicial fact. A passer-by cannot

be guilty of failure to try to prevent a lynching. He can only be ashamed

of not having done so" (Mayer, 181). From this, Mayer concludes that

his friends feel little personal responsibility or shame for the actions

taken by Nazism throughout 1933 to 1945. At one point or another, almost

all of Mayer's Nazi friends use the phrase, "so war die sache,"

meaning "thats the way it was" (Mayer, 93). This phrase exemplifies

what the author believes to be a rather laissez faire attitude about Nazism,

the Nazi movement, and ultimately the destruction that the Nazi regime

brought about in Europe. None of Mayer's ten friends feel extreme shame

or guilt for their involvement in the Nazism party, for this reason, the

author does not address the fact that there were many Germans in the post-WWII

period who did admit strong feelings of guilt, and express that through

depression or in some cases suicide. Despite Mayer's failure to discuss

Germans that felt guilt in the post war period, the author still draws

some astute conclusions about the 'average' German's reaction to the Nazi

movement.

Although Mayer fails to explore some specific cases, exceptions to

the 'average' German, such as Germans who resisted Hitler and Nazism or

Germans who expressed great shame and remorse after WWII, the author ultimately

provides readers with a look into the lives of ten Nazi men and is able

to effectively draw some conclusions about the lives of 'ordianary' Germans.

Mayer achieves his main goal in writing the book: to give Americans insight

into the lives of 'ordinary' Nazis. Mayer's analysis of why his friends

chose to join the Nazi movement, why they did not resist, and how they

feel about Nazism in its aftermath is a valuable source of information.

While there are elements of Germany's political culture and history that

are unique to the German people, the author ultimately proves that the

Nazi movement, or one similar to it, could happen anywhere and to any people.

Mayer's message is a warning to current and future generations that something

like Nazism could happen again. |