Essay (back

to top)

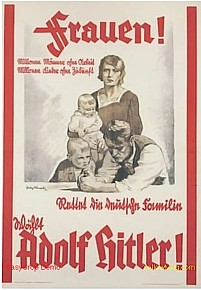

When thinking about the Nazi era in Germany, one usually

thinks about the racial tension and violence ensued over Jewish people

by the “Aryans.” The gender relations are hardly discussed or thought about,

as the focus lies more on the systematic extermination of hundreds of thousands

of people. However, centering the research on women’s daily lives can also

give us insight of what it was like to live in Germany during the first

half of the 20th century. Matthew Stibbe’s book, Women in the Third

Reich, gives attention to the daily lives women in Germany lived during

the infamous time of Hitler’s reign. He strives to demonstrate the diversity

of the experiences women had. There was no such thing as dichotomies but

a complex variety of participation and exposure to harm. Stibbe does

a great job at giving more than one perspective, however the book fails

to really grasp the differences among certain classes of women by only

focusing on two extremes when analyzing history. Women in the Third Reich

is also primarily a collection of previous research rather than Stibbe’s

own analysis as such, the book serves as a great consolidation of various

sources into a thin book that allows for a quick read. Stibbe also exposes

the contradicting policies Nazi Germany enforced and how these affected

women.

One of the purposes of Stibbe’s book is to really diversify the experiences

of women in the third Reich. He does this by dividing the book into chapters

dealing with distinct subjects and how they affected women. He also differentiates

women’s experiences on the basis of “age, class, religion, race, sexuality,

and martial status” as they all contribute to “determining the impact of

Nazi policies on women’s lives” (Stibbe, 2). He also stresses the fact

that although race was the major player in Germany, gender was also involved

in deciding the role men and women took in society. During the Weimar Republic,

German women were influenced by the “American wave” of the concept of the

new woman (Stibbe, 10). While in some places this new identity was embraced,

in others it posed a threat for the national identity. This was especially

true during the Nazi reign, as nationalism became an important part of

the party. They wanted to be able to control women’s identity and hence

women’s bodies by taking away their agency. Another issue was that families

were having fewer children. Hitler stressed the need for women to become

the mothers of the nation. Their purpose was to stay at home and procreate

so that the future of the “Aryan” race would be cultivated. Women were

in support of this since older thoughts about gender roles were still in

place.

A major contradiction of women supporting Nazism is that the party

was extremely anti-woman. They did not have any women in the party and

did not want any of them involved in party matters. Those of the middle

and upper-middle classes would not mind this policy, as they were comfortable

living their daily lives. They supported the party indirectly by cooking

or sewing for the soldiers or the party members (Stibbe, 18). There were

others who began small groups of women involved in politics. Most of their

work centered on anti-communist sentiments but several groups were Nazi

sympathizers. The main purpose of these groups was to conserve the gender

roles already set up by Hitler; they were to procreate, stay at home, and

care for their husbands. Ordinary women were also involved in these groups

but “less evidence is available” of their reasoning (Stibbe, 20). However,

Stibbe also claims that they “showed a strong tendency to identify with

middle-class values and aspirations, were fiercely anti-communist and anti-socialist,

and came overwhelmingly from Protestant backgrounds” (Stibbe, 20). Hitler

and the Nazi party realized that women’s political power was rising and

should be kept under careful observation. The party was inconsistent with

their stance on keeping women away from politics when they actually wanted

women to vote for them during elections. However, this was the only active

way that women were supposed to be involved with politics, according to

Hitler.

During the depression, women were forced to stay at home so that the

unemployed men could take their jobs. Most well-off women did just this,

however those that were in need were unable to survive on just one wage.

Middle class women who were active in women’s group experienced more of

a split in ideology than having to deal with economics. There were some

that wanted to continue the “anti-women” ideals, there were others that

were adopting feminist ideology, there were women that were not involved

but wanted more options when voting for different political parties, and

there were some more inclined to vote for the NSDAP because of its pro-Church

stance. During and after the depression, the women’s voice was scattered

around different issues and because the state was concerned with the economic

situation, the women were left to deal with their own problems. Discontent

came from women academics who felt they were limited on what they could

do within the party, after the creation of the NSF which was supposed to

consolidate all of the women’s groups.

When dealing with race, Stibbe notes that it is difficult to separate

racism with sexism, hence, he only focuses on “Aryan” and impure women.

It affected women’s lives specifically through the control of their bodies

by policing women’s “choices in the sexual and reproductive sphere” (Stibbe,

59). In this area he draws a distinct contrast with “Aryan” women and those

that were racially impure. While the “Aryan” women were encouraged to produce

more children, those that were unfit for the race were forced to halt their

procreation through unwanted sterilization or abortion. Class was not a

factor in the dehumanizing process, as many women were forced to take humiliating

jobs regardless of their education. Women who were married to Jews also

had to divorce their husbands and face public humiliation (Stibbe, 68).

The way the social hierarchy was organized was “ the ‘Aryan’ over the Jew,

the wife over the husband and the mother over the childless woman” (Stibbe,

70). With this, the author describes how various elements intertwine to

oppress women of Germany at the time. He compares these groups of women’s

experiences with the overarching theme of race and then goes into class

and marital status.

Women in the workforce also had a hierarchy in social status according

to Nazi policy. Middle class women and wives of prominent Nazis were not

recruited for work as much as poor working class women during the war years

(Stibbe, 95). However, even recruiting women for work was contradictory

to the Nazi party as the need to have more women in the labor force was

important, they also thought that women should only be used as an “emergency

measure” (Stibbe, 87). Jewish women were not part of this measure; in 1941

all Jews regardless of gender were order to enter the work force so that

their labor could be exploited to the fullest (Stibbe, 97). “Aryan” women

also worked in much better conditions than the Jewish women did and had

more comfortable posts and flexible working hours. Polish and Soviet women

were also victims of slave labor and were sometimes treated worse depending

on the region they were working in. Those living in the eastern side were

treated more harshly than those in the west.

The education sector and its impact on the youth are also described

in the book as not having a clear-cut purpose in establishing gender norms.

Although in theory, girls were supposed to be trained in housework, after

the war began more girls were pushed into agriculture and nursing to assist

in the war effort. The conflicting ideology clashed when Nazis wanted to

keep women out of higher education but needed more women in the “caring

professions” such as social work, nursing, and teaching (Stibbe, 111).

Joining youth groups like BDM (League of German Maidens) increased as more

pressure was put on having a national identity and girls saw this as an

act of rebellion in order to be incorporated in activities usually reserved

for boys (Stibbe, 114). However, this was not the case in bigger cities

such as Berlin where girls had more entertainment opportunities. During

the war work draft, many girls began to be in opposition of the state because

of the lack of liberties they once had. By the end of the war, many of

the girls no longer supported the state as strongly as they had before

(Stibbe, 124).

The final chapters discuss the sentiments of opposition women had towards

the state. Stibbe notes that women who were in resistant groups joined

because of feelings of discontent with the state, not because they had

a feminist agenda per se. Another group of women who were involved were

highly religious women who were opposed to “euthanasia” procedures and

racism (Stibbe, 130). There was another group whose acts of kindness were

seen as acts of resistance and hence reprimanded. Although men were persecuted

more than women, women were still subject to the same treatment as men

dissidents. Those women who were more actively involved with leadership

positions in oppositional parties were seen as secondary to the men in

those parties (Stibbe 134). Sometimes they had protection by other party

members but women who would resist in solitary acts would take a more lonely

road; especially those who were in opposition because of religious beliefs

since the church did not support any acts of resistance towards the state

(Stibbe, 136). This chapter mainly highlights the lives of women or groups

of women who remain in history as heroic dissidents of the state. It is

different form the rest of the book where distinct groups of women’s experiences

were compared.

The last chapter is an overview of how women dealt with the “woman

question” during the final stages of the war. The food shortages sometimes

pitted women against each other, especially those with privileges (i.e.

Germans) and those without (i.e. Russians). Marriage was also difficult

to maintain especially when husbands were at war or if single women did

not have a place or time to meet other single men. Sexuality still continued

to be policed as contraceptives were banned and women were encouraged to

have more children, even if their husbands were at war (Stibbe, 156). Although

prostitution was banned, official brothels were allowed for soldiers. These

contradictions in Nazi policy created confusion were women were random

victims of humiliation and torture. By the end of the war “suicide, abortion,

and sexually transmitted diseases” were prevalent as soldiers raped women

to “retaliate” against Germany (Stibbe, 156). A significant fact in post-war

Germany was that the population of women was greater than that of men.

It hence became a country of women.

Stibbe’s Women in the Third Reich covers problems women faced

during the Nazi reign: education, labor, and sexuality among others. He

recounts their experiences through different social lenses in which women

were observed by the state. One of the take home messages in the book is

that whether racially or by class, women did not share a homogenous experience

in the early 20th century. Another point that is maintained throughout

the book is that of the contradictory nature of Nazi policy, highlighting

women’s agency in the state. His narrative covers various sources in a

compact book that allows one to read through it and make inferences or

create questions than can be further investigated. This book emphasizes

that although gender was intertwined with other social identities, it should

still be looked at and analyzed on its own.

|