Essay (back

to top)

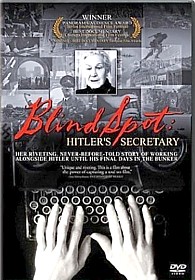

Coming to Terms with Your Savior, a Mass Murderer

It is 1945, and Germany has lost World War II. The German people must

rebuild their war-torn nation, and in the process they must deal with

the realization that they stood by and watched as millions of people were

unceremoniously killed. Traudl Junge was Hitlerís personal secretary for

the last two and a half years of the Third Reich. In Jungeís memoir, "Until

the Final Hour," Junge portrays her close relationship to the Fuhrer

up until he committed suicide in his bunker. Even though Junge claimed

that she was not an avid Nazi, or greatly involved with politics, she

still adored and respected Hitler very much. The experiences that Junge

encountered, from her adoration for Hitler to the guilt that she felt

postwar, represents the sentiment of the majority of Germans. However,

unlike many Germans who tried to claim that they were victimized under

the Nazi regime, Junge took responsibility with her involvement with Hitler.

She never pitied herself. As a result, the unforgiving compunction that

Junge developed plagued her for the rest of her life. Other Germans wanted

to ignore the past and the Third Reich altogether.

In her memoir, Junge explained that she was not aware of the millions

of people who were being executed at the hands of Hitlerís men because

she was isolated in the bunker. She stated, "That never occurred

to us at the time, and isolated from the experience of other Germans,

we accepted as normal our not only very privileged but our entirely abnormal

life." Perhaps Junge was not aware of Hitlerís crimes, but she was

present while he was dictating his speeches to her, and in many of his

speeches he expressed contempt for Jews, and other people of "Non-Aryan"

descent. The myth of ignorance was a common German reaction to their involvement

with the war. The "we didnít know," myth, turned to "we

donít want to know" (Marcuse 01/25/06).

Traudl with Hans and best man after wedding |

Germans chose not to know because they did not want to come to terms

with the crimes they had committed. Also, by portraying the myth of ignorance,

it lifted some of the blame that Germans did not want to have on their

conscience. Junge claims that she was not aware of Hitlerís atrocities.

But Melissa Muller, the editor of Jungeís memoir says that Junge probably

did not know the extent of the persecution of Jews because she did not

want to know (Muller 218). Junge stated, "Most of the time I try

to sleep, to take my mind off of bitter memories of the past and anxiety

about the future" (Junge 227). Junge also tried to relieve her guilt

by believing the excuses that people made for her, such as "But you

were so young at that time," or "There was nothing that you

could have done under Hitlerís power. These excuses kept her somewhat

at ease up until the 1960s. The 60s was the generation that confronted

their grandparents about their involvement in the past. Her memories haunt

her, but she still tries to ignore them.

Unfortunately, the Holocaust cannot be forgotten. For many Germans like

Traudl Junge and Professor Mahlendorf, the guilt for what they were a

part of grew as they got older. Junge went through many years of depression.

It was only at her death where she barely started to forgive herself.

Professor Mahlendorf also had to go through many years of therapy to help

forgive herself for her role during the Nazi regime. As she expressed

in her lecture, the older she gets, the harder it is to live with what

she had done. The notion that many Germans did not want to know what had

happened during the Nazi regime shows that during denazification, Germans

were renazifying Germany by ignoring the situation at hand. Moreover,

Germans did not talk a lot about the Holocaust. They went on with their

daily lives, trying to suppress their guilt. It is important to note that

Germany was quiet about the Holocaust after the war because there were

not that many Jewish people alive or living in Germany to tell their stories.

Most Jews had fled or were killed in the concentration camps.

Furthermore, another myth that Germans used to justify their involvement

with the Nazi regime was the myth of being victims to the Allies, and

people who wanted money to pay for their grievances. Germans claimed that

they were victims of a totalitarian government.

Another myth that Germans used as their reaction to the war was the myth

of resistanceóthey resisted as much as they could under a totalitarian

government. Hitler had total power, if they rebelled; they put their lives

in danger. Therefore, they did as much as they could to resist the Nazi

regime. Later, Germans felt that in terms of resistance, most Germans

already know enough about the atrocities and now they need to clean up

the sites. Germans wanted to forget about the testimonials of the survivors

because they felt that it was not important. They wanted to just forget

about everything that happened. Forgetting seems like an easy way out,

but as the tragedies of the Holocaust were more revealed in the 1960s,

Germans could not simply forget about it (Mahlendorf 02/16/06).

Finally, the last myth was the myth of victimizationóthe "good Germans"

were victims of "Bad Nazis. (Marcuse 01/25/06). Hitler had instilled

a notion into German minds that Germany can only thrive by National Socialism.

This idea is expressed when Frau Goebbels, the wife of Joseph Goebbels

who is Hitlerís Propaganda Minister, says that she would rather commit

suicide than live in a world that was not ruled by National Socialism.

She also ended up killing her six children once she realized that Germany

had lost the war. Even after the war, Germans felt that they were victimized

by Allied troops who celebrated their victory on German land. They also

felt like they were victimized by tourists who would always remind them

of the atrocities during World War II.

|

After the Nazi regime came to an end, Junge had to deal with the fact

that her Fuhrer was responsible for killing millions of people, and for

the downfall of her nation. Like many people, Junge had a magnetic-like

attraction towards Hitler. Mainly because Hitler held a great deal of

power, and at the same time, he had two sides to his character. Around

Junge, Hitler had a charming, caring, and paternalistic behavior. He always

made sure that she was fine and had everything that she needed while in

his company. For Germany as a whole, he was also portrayed as a paternal

figure that would take care of Germany. Therefore, it was very hard for

Germans to come to terms with Hitlerís end. Many were in denial even decades

after the war was over. Germans took on one of the three myths mentioned

previously as well.

Most of the Jews had either died during the war or left Germany. There

were very few Jews still living in Germany in 1945, so there was little

contact between Jews and Germans (Mahlendorf). There was such a small

number of Jews in Germany that the first time that Mahlendorf personally

met a Jew was when she came to the United States as a Fulbright student

in 1951. After learning about the concentration camps and racism during

the war she felt ashamed around them.

Germany was so brainwashed with Hitlerís hatred for Jews and people who

were not Aryan that the reversal of ideology was a difficult task. As

the Nazi regime was coming to an end, there had been some realizations

that the regime had been lying to the German people. For Professor Mahlendorf,

her reversal of ideology occurred during her high school years. From witnessing

the Nuremberg trials, comparing constitutions, and learning from her teachers

who were never affiliated with the Nazis, Mahlendorfís ideology had been

reversed. But for the most of the German population, it would take the

1960s for the reversal of ideology to occur. Postwar, Germany attempted

to make amends by paying reparations to Israel and Jewish families. However,

the racism was still very prevalent in Germany. As portrayed in "Invisible

Woman," Ika experienced a brutal amount of racism and discrimination

in her lifetime for being half black. Nevertheless, Germany definitely

has a very complex past that many Germans today have to still live with.

Junge describes in her memoir that she felt betrayed because Hitler made

Germans believe that they were superior to everyone else and that she

always felt safe under his paternalistic demeanor. However, a new light

was shed in her life when she became close with the Lanzenstiel family

in the 1960s who never got involved with the NSDAP. She learned tolerance

and acceptance from them because they accepted her no matter what. The

mother of the family, Luise Lanzenstiel made Junge feel comfortable at

a time when Junge wanted to "hide from the rest of the world"

(Muller 246). Junge feels safe with the Lanzenstiel family.

Naturally, the men and women who had a direct involvement with the Nazi

regime are at fault. However, it is everyone who participated in anti-Semitism

for whatever personal reason to accept the burden of the past and work

hard to make sure that events like that will never occur again. Even though

Junge never committed any crimes herself under the Third Reich, she still

feels guilty for not having enough self-confidence to speak out against

the Regime. Junge took responsibility for her involvement in the regime,

which is the first step towards forgiving herself. Traudl Jungeís memoir

exhibited the influence and hold that Hitler had on the German people

during World War II. Hitler and his menís last days in the Bunker is a

reminder of how strident political beliefs can take over an entire country.

Eventually, these beliefs led to Hitlerís suicide.

|