Essay (back

to top)

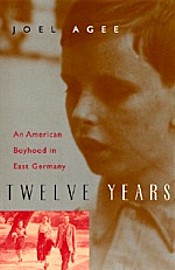

After the collapse of the Third Reich, the two halves of Germany were split, with West Germany controlled by the United States and Western countries, and Eastern Germany in the hands of the Soviet Union. This left people with nothing but their stereotypical concept of life in East Germany: common thoughts and ideas, a life where idiosyncrasies were frowned upon and punished. Usually stereotypes fall flat in the face of reality, but in Joel Agee's memoir, Twelve Years: An American Boyhood in East Germany, his life seems to at least somewhat reflect these realities. Agee expresses the experiences of his childhood through written word, giving the views of a boy to the historical events previously available mainly through the news and reports. Yet it is not historical events that most affect Agee's life, but his emotional concerns. He loved and lost, attempted to work at school to fulfill societal and parental demands. Failing at that, he tried to gain acceptance with the children at school when he was young and was afraid to be different. However, those are normal aspects of human life, not indoctrination of Communist ideals. His story was moving, and it is evident through his words that Agee was an intelligent, gifted boy with great potential, and his story was fascinating to read. It was not, however, the legacy of Nazism or the current Communist regime that seemed to rule his life in this memoir, but the social interactions of an average boy struggling to become a man.Through his own experiences, Joel Agee illustrated to his readers the reality of an Eastern German childhood with all of its usual difficulties and tribulations: love, relationships and familial problems. Yet though Agee's own personal happiness is what guided his successes and failures, it is clear that the Communist government in many ways influenced his life in East Germany. There is no doubt that the remnants of the Holocaust and the war affected the life of every individual living in Germany, and it is apparent that Communist ideas did create more turmoil in Agee's life than he realized, by trying to force him to live his life a certain way, follow a certain path, and fit in with others, but his story is not the story of a tortured victim of Communism, but the story of an average adolescence anywhere with all the freedoms and tribulations that come with it.

The sub-title of the book An American Boyhood in East Germany truly reflects the message Agee is trying to imply, that he still had an American boyhood, because boyhood comes with its ups and downs regardless of where one lives or what regime one lives under. Childhood was a time for relationships, friendships and family, and the age group that grew up after World War II in East Germany was not greatly influenced by the wall. In the story, Agee moved from Mexico to Berlin by way of Leningrad, when he was eight years old in 1948. His first impression of Leningrad came from a group of young boys who were running alongside the shore near the approaching boat appealing to the sailors for cigarettes. Agee admired them, “their independence, evinced not only by the absence of supervising adults but by their familiarity with tobacco; the way they had all that territory to themselves” (Agee 3). This admiration is not a judgment about political liberties, but a yearning for freedom that boys have anywhere.

Agee's first years in Germany, from 1948 to 1955, take up the great bulk of the text, mainly because it was in those years that he was most influenced by the East German situation and in those years he did most of his developing. The first part of his time in Germany seemed to be focused on finding friends and finding a way to fit in with the other boys, as boys do in all countries. Agee does not experience any hatred toward him for his race because “making racist remarks, let alone disseminating them through the media, was a punishable offense,” and the children were “informed of what the Nazis had done. Whether they liked it or not they were informed” (39). This seeming attempt to restore Germany to its righteous past before World War Two's racist history was effective for Agee who seemed to feel no racial tension or stigma for being a foreigner and having a Jewish mother. He was however astute enough to realize that his mother was more affected by life in Communist Germany than he was. The Soviet control of the border did not concern Agee in the slightest because children are exempt from the rules and he was still allowed to go to his volleyball games despite the anti-fraternization laws (70). It was situations like this, where the laws that so constrained adults were not applied to children, that make it apparent that life was perhaps more controlled for adults, but for children it remained largely the same as life anywhere else. The children knew of “the West and everything connected with it-- sports, politics, citrus fruits, espionage, money, modernity, glamour” -- but they also considered it “ 'drüben,' ‘over there .' And regardless of how you felt about it, ‘ drüben' was a foreign counry” (61). In the life of youth, it was the relationships and things that were actually in their lives that mattered, and thus life in East Germany was not any different than the life of an American child who wished she could play with Chinese dolls rather than American.

Agee was taught from an early age to understand that the ultimate goal that the Communists were trying to reach was a place where “there will be no more state, just people living and working together and helping each other. And enjoying it, too. Ultimately, joy is what it's all about.” He was more than willing to accept this explanation. His stepfather Bodo, with whom he lived, was a Communist who worked hard throughout the war to try and create a new state. Thus Agee was influenced by these ideas, but he was also lived with a mother who was not entirely comfortable with the system. Agee participated in the Communist youth organizations, and went to the public schools all children in East Germany were allowed to attend. Yet he did not perform to the standards his family, with a high-ranking official at its head, wished he would achieve. It is clear, however, through Agee's angst ridden sexual fantasies and his lack of motivation to succeed, that Agee is not influenced by Communism's attempts to make him fit in, nor are his friends.

There is evidence in the text, however, proving that Agee's life was more greatly influenced by Communism than he realized. This is probably partially because he was an underachiever who did little to interrupt the system, and also because he was so focused on seeking happiness through relationships and friendships he did not realize the impact the government was having on his life. When Stefan, Agee's brother, tried to start a student newspaper for Young Pioneers, the Communist student group, he was told that it would have to “have a certain line, a definite cultural and political profile. It would have to be educational as well as entertaining and informative” (169). But not only would the paper need to be informative, it would “have to truly represent the Young Pioneers,” and Stefan was welcome to collaborate with the editor, but he would not be able to write or edit the paper (169). The Party did not want its youth to have their own voice, because they needed to continue to influence their developing minds. The goals of reeducation were to rid the generation of the ideas of Nazism, and in order to do this they influenced student's opinions. It is evident that it was the adult generation who so strongly supported the Communist system though, when Joel and Stefan's parents realize the wrong the Party is doing, but will not do anything about it because Bodo fought for too long to let the West win any points against the East. They were willing to take the bad traits because they felt that in the end the good would be overwhelming. This attitude proves that perhaps the reason Agee was not as indoctrinated into the Communist way of thinking was because he had an American mother and a family who accepted other ways of life, but believed that Communism was better and could explain why.

Although matters are taken more seriously in East Germany, when Agee is sent to trial because he has not been attending classes, the goal of his parents' and the Party as a whole is still the same: to educate the youth (207). Agee's parents and schoolteachers respond in the same way that any parents in the West would respond to a child not achieving his potential, they get him tutors and try to convince him to succeed in school so he will not have to go to work. The Party's efforts to make him perform to his potential were no different than a father in politics in the West trying to ensure that his son or daughter presented a suitable image to the public. The Party as a whole did play a more influential role in Agee's life than other governments would play, but Agee was the son of an important man. Still, the efforts to thwart his laziness did not achieve their goal since he went back to his habit of skipping classes later in his life. The most obvious indicator that perhaps Agee was being manipulated by the government, but was too concerned with his own personal woes, came when he returned home from school after the nation discovered the crimes of Stalin. At school Agee and his teachers did not question that mistakes had been made but the new government was making them right, yet at home Agee finds that Bodo is devastated that the man he spent his life working for and defending was such an awful man. Bodo and his generation are a generation of fighters, men who believed in Communism and fought for it, while Agee and his generation were simply accustomed to the lack of personality in East Germany.

In his later childhood, Agee did as most teenagers do and slipped in and out of realization of a world outside his bubble, from thoughts only about trivial personal matters to a shocking awareness of outside reality. It was after his realization that Egypt was being bombed by Israel, and his father was scared for their family's life that he comes to realize that he doesn't believe in anything at all anymore (188). Rather than do as he was supposed to do and influence him to support Communism, growing up in a Communist country did not affect Agee's political apathy at all. He was simply a self-absorbed teenager growing up in Germany. When familial troubles forced his mother to decide to move back to the United States, Agee felt that “trading a socialist for a capitalist country didn't trouble [him] in the least: what bearing did it have on [his] personal happiness?” (315). This attitude that his only reason for deciding where to live was based upon his personal happiness and an ability to start over and erase his mistakes makes it evident that Agee's childhood in East Germany influenced him in similar ways to Western children are raised today. He was well-educated, and his education was biased against Capitalism, but he saw either system as a way to gain happiness, and that was what he ultimately wanted in life.

|