Essay (back

to top)

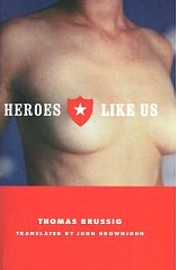

The book Heroes Like Us by Thomas Brussig is a satire on the life of a fictional Stasi agent named Klaus Uhltzscht. The story is presented through Klaus sharing his life experience, focusing on his perverted sexual acts, his profession as a Stasi agent, and how he believes he is responsible for the collapse of the Berlin Wall. The author’s main point in this fictional book is that the Stasi as a group of politically indoctrinated, perverted morons who targeted people for trivial reasons. The satirical nature of this story makes the Stasi seem laughable, but in reality it was one of the best secret police forces in the world.

The political indoctrination Klaus received as a child helped him gain a love for socialism, molding him into a perfect Stasi agent. When Klaus discusses his childhood he recalls a time when he observed a globe of the earth which mapped out the historical advance of socialism and claimed, “I was on the red side, the winning side” (Brussig 76). The belief in socialism’s inevitable worldwide success was a key tool in the indoctrination process. By accepting socialism’s coming victory, students with dissenting views would only have to look at the recent historical events of socialism’s expansion to see the greatness of their system of government. Klaus also recalls hearing the stories of “Teddy in the Prison Yard” and “The Ballad of the Little Trumpeter” (Brussig 77,78). These two stories about the German communist leader Ernst Thälmann were taught to inspire the East German youth to stand up for their German communist heritage and see the former KPD leader as a hero defying both assassins and Nazis in support of socialism. After hearing the Little Trumpeter story in which a young boy takes a bullet intended for Ernst Thälmann, Klaus himself declared, “I would sacrifice my life for a higher purpose” just like the Little Trumpeter did (Brussig 79). Throughout the book Klaus compares his actions to those of the Little Trumpeter and claims that he is defending socialism, allowing the reader to believe that his childhood indoctrination had a lasting effect on the way he viewed the world. Another important element for Klaus joining the Stasi was the fact that his father was “in the top 300 salaried employees of the Stasi” (Brussig 209). By having a father who was top Stasi agent, Klaus was always curious and inquisitive of what his father really did. His curiosity about his father’s activities led him to imagine a fantastically elaborate organization of elite spies who targeted high ranking NATO officials who were major threats to socialism.

The East German government did go to some extreme means not addressed in the book to indoctrinate children into believing in socialism. For example, in 1953 “A twelve year old boy in a Dresden school claimed not to hate Western leaders, and therefore was expelled from school, and his parents were threatened with “reprisals” (Prittie 117). Those who refused indoctrination into anti-capitalist beliefs were persecuted by the East German government. Klaus’ story is factual in regards to how “Children as young as 11 to 14 are encouraged to attend defense education classes were they are taught the wartime heroism of communists” (Ardagh 357). These real stories that were discussed in the book about the Little Trumpeter and Red Teddy in the prison yard show how the East German youth were taught to further advance their love for socialist ideals. This indoctrination process allied the citizens of East Germany to their government and discouraged them from opposing the SED. The idea of Klaus receiving a position in the Stasi because of his father is based on historical fact because “Reproduction of inherited status was reappearing” by 1980 in East Germany (Fulbrook 189). This shows that Klaus was more likely than other East German candidates to get a position in the Stasi because job titles were becoming more subjected to family influence as time progressed.

Klaus shares some of his activities as a Stasi agent and discusses what the Stasi does. Klaus had a false understanding of what the Stasi really did; throughout his entire training he still was not even sure he was a member of the Stasi. Klaus’ Stasi life is comprised of mostly boring endeavors such as ensuring the organization never ran out of pretzels ( Brussig 121). Since Klaus’ superiors pay so much attention to the importance of pretzels, Klaus’ understanding of the Stasi to be a super elite organization falls short. Klaus is also unimpressed with the boring surveillance missions. His commanding officer Owl reminds him that, “You’ll appreciate a good surveillance spot like this, give it a couple of weeks… or years” (Brussig 150). Owl’s quote implies that Stasi agents could spend years watching people they deemed dangerous, but Klaus could never understand exactly what they were looking for. Later in the story Klaus discusses how his fellow Stasi member and friend René was ordered to “Monitor live radio broadcasts … [and to] Prevent undesirable conversations and if necessary cut them short” ( Brussig 225). René never once intervened in any broadcasts and could not understand how protesters were organizing in Berlin when no one ever spoke about the protests over the radio waves he was monitoring. Klaus and his fellow Stasi members made their professions sound boring and frustrating. The real Stasi were determined to keep dissenters from speaking against socialism.

The Stasi portrayed in the book seem laughably awful, but this was an organization created with a specific mission to control threats to socialism. The original purpose of the Stasi organization was to control the unrest in East Germany after the 1953 workers riots. Once this organization was created it began to expand in a “mushroom effect” to gain insight into every aspect of the lives of East German citizens (Fulbrook 212). The Stasi organization had “one and a half times the personnel of the GDR army” as well as hundreds of thousands of informers (Funder 56). The Stasi were to be “the shield and sword of the SED” whose goal was to “Protect the Party from the people” (Funder 57). The Stasi organization’s grip affected everyone in East Germany. In fact, “one in every seven East Germans collaborated with the Stasi,” making their organization one of the most extensive police infiltrations of a society in history ( Rosenberg). By having collaborators in all levels of society the Stasi could keep watch on everyone and then send their agents to focus their observation on citizens who were suspected of dissent by their fellow Germans. The Stasi were responsible for the killing and imprisonment of thousands of Germans; a few instances of people the Stasi targeted are discussed in the book.

The types of people who Klaus and his team targeted were labeled as arch enemy individualists who were selected to be spied on because they did not conform to the socialist system. Klaus’ first action he took against his fellow East Germans was to kidnap the daughter of a woman he referred to by the alias of UI Catalogue, “a librarian who played Monopoly on New Year’s eve” ( Brussig 184). Klaus felt that the kidnapping of a child for playing a game that emphasized western economic values felt like a punishment which far exceeded the crime. But Klaus didn’t put too much attention to his orders and concluded that, “It seemed logical that I should start with kidnapping children and gradually perfect my technique until the day came when I would carry off fifty million NATO Secretaries-General at a stroke” (Brussig 185). Klaus believed from the very beginning that he was destined to be a great Stasi agent who would be a superior infiltrator commando. Some of his other assignments made him feel less impressed with his profession, like when Klaus’ team was ordered to an anti-socialist protest rally where he would “arrest any subversive-looking individuals [at the train station]” (Brussig 225). Klaus was confused and angry at his orders because he had no idea who was a protester and who was a faithful citizen. The confused nature of who the real enemy was is evident throughout the book. Unlike Klaus, however, real Stasi agents had a much better understanding of who to be watching.

The real people who the Stasi targeted were from all aspects of East German society. The famous German writer Wolfgang Harich was sentenced to “ten years imprisonment for moral weakness and human fallibility” (Prittie 124). The SED determined that some of Harich’s ideas about socialism were too radical and that he must be silenced before becoming a serious challenge to the regime. Harich’s example proves that not only were the Stasi interested in those who desired capitalism, they also attempted to control dissenting ideals about socialism. Another example would be the case of three soccer players targeted by the Stasi, “Matthias Miller, Gerd Weber, and Peter Kotte who all played for the team Dresden Dynamo,” who were suspected of intending to leave for the west. Due to the popularity of these three famous sports stars rather than allow them to leave for the west as an example for other East Germans, the Stasi decided to never allow them to play soccer again (Epstein 7). Even normal East Germans with no political designs were targeted. A typical German couple Miriam and Charlie Weber once had their house raided by Stasi agents and the agents found the banned book Animal Farm. After that raid neither one of them would be hired into jobs fitting to their qualifications because the Stasi contacted their potential employers and forced them to deny their applications (Funder 34). The Stasi proved its superiority over the East German people by leaving no person unwatched. These secret police agents and their faithful collaborators kept the GDR under constant surveillance to maintain the political control of the SED.

The majority of the book is spent discussing Klaus’ repressed sexuality. Brussig includes this element of the story to further defame Stasi members as being perverts. Klaus claims that, “I considered myself to be one of the most perverted individuals on the face of the globe” (Brussig 46). His perverted fantasies and dreams makes the book’s audience believe that all Stasi members who watched female Germans were probably perverted like Klaus and had sexual fantasies about the women they spied upon. As the story progresses Klaus becomes more frustrated with his assignments as a Stasi agent and he feels he would never gain recognition as a national hero. So to make his talents known to his fellow Germans he decided to write a book about perverted activities, claiming “I’m jerking off for Socialism” (Brussig 160). His private life of compiling a book about perverted actions like having sex with dead chickens leads the reading audience to believe that all Stasi agents were perverted individuals who composed strange literature in their spare time. Unlike Klaus’ example, history shows us that Stasi agents were not all perverted megalomaniacs.

The real agents of the Stasi were normal people but fiercely committed to preserving the status quo in East Germany. The leader of the Stasi was Erike Mielke who was described as a man who “loved to sing and hunt… [but as the director of the Stasi] he was certainly the most feared man in the GDR” (Funder 57). Mielke’s tactics of violence and intimidation led many to believe that he held more power than Honecker in the 1980s. A lesser Stasi agent named Herr Bohnsack reflected on the riots which preceded the downfall of the SED, “I am thankful I was never ordered to fire on the demonstrators” (Fudner 239). Bohnsack shows compassion here for his fellow Germans which proves that Sasi agents were not all obsessive stalkers like Klaus. Many of the former Stasi agents who now live in united Germany reflect on their time as agents saying, “they worked hard to foster world peace and protect German citizens” (Epstien 15). These real Stasi agents reflect a lot of the same motivations as Klaus did in the book, they were not perverted moronic individuals, but rather they were loyal followers of their country who felt they were doing a service to their communities.

The portrayal of Klaus Uhltzscht in Heroes Like Us gives readers a satirical look at the life of a Stasi agent. Brussig’s interpretation of secret police agents is farfetched and laughable, but there are many elements of truth in his story. Perhaps the best thing to learn from his book is that Stasi agents were not terrible heartless human beings, instead Klaus refers to his fellow Stasi in a warm light, referring to them as “Heroes Like Us” because they committed their lives to making their fellow citizens safer (Brussig 20). Klaus was a clueless, harmless character who no one would expect to be a Stasi agent and perhaps that holds the greatest relation to the real Stasi because in East Germany Stasi agents and collaborators were not always who you would expect. |