|

Essay (back

to top)

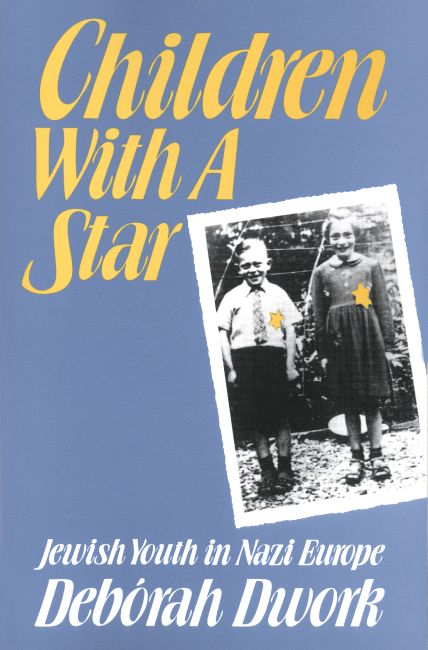

Deborah Dwork’s Children with a Star: Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe attempts to show the experience of some Jewish children during the Holocaust. Dwork believes that children have been a largely neglected part of the Holocaust story; their journey and experiences show the cruelty of the Nazi regime because the children involved were completely innocent and blameless. Dwork focuses on the attempt to find out what life was like for children during the Holocaust and how they dealt with the daily persecution. I found that the children’s main attempts to cope were to maintain a daily routine--such as schooling or jobs--and that this became the most consuming aspect of their lives. The children were forced to create their own fantasy worlds and became desensitized to the atrocities that they saw. They ultimately had to give up their childhood and their identity in order to fight for survival.

Dwork had many difficult questions and hurdles to overcome when researching this topic. Children in the Holocaust did not often leave a paper trail and it was difficult for them to document what was happening to them at the time. One difficulty was trying to find children survivors to give oral histories. The oral histories that she was able to compile were sprinkled throughout the book, and added a voice to the horror that was taking place. She was able to find some journals and documents from the time period, because of the organizations and social workers who were allowed in the camps and ghettos. These provided another layer to the picture that she was able to create about what was taking place. While the topic posed problems, the sources that Dwork was able to utilize provided a well-rounded picture of what was taking place and how these children dealt with the atrocities they were forced into.

Some of the questions that Dwork addressed were how to define a Jewish child and how these children were able to handle what was taking place (Dwork, xvi). Dwork attempted to discover what coping mechanisms were used, and what the daily life of these children was. Preserving a normal childhood was nearly impossible, but this did not stop attempts to create an environment, as close to what was normal as possible. Throughout the book Dwork also attempts to show what happened to familial relations and the role reversals that may have taken place. Dwork is able to address these questions in a very thorough way. She shows the progression of laws by the Nazis and what would have been like at each stage—in hiding, transit camps, ghettos, and death camps.

The book is organized into chapters about the different environments of these Jewish Children. The book starts in the home and moving through hiding, transition camps, ghettos, and ends with death camps. Each chapter explains how children coped and how their lives progressed. In each circumstance some things helped to make life easier to cope with for the children in these circumstances. Having a loving and supportive network or family provided comfort to children in hiding. Coping mechanisms also existed such as shutting off emotions and thought or creating a new idea of what was normal. At each of these stages certain fears and themes persisted—hunger, anxiety, loss of emotions and a final loss of identity. It appeared that the Nazi implementation plan worked thoroughly to dehumanize many Jews and the Jewish children were no exception.

In some extraordinary circumstances Jewish children living under the Nazi regime were able to participate in the development of music, arts, and Zionism that was able to take place in some areas. These activities were a chance to fill the day and create a daily routine. The children were given some structure and a chance to have a normal childhood. Within the transition camp Terezin operas were put on and children were encouraged to attend concerts and lectures (Dwork, 125). In some areas children experienced a full life with many opportunities to learn and participate in cultural activities. Ballets and plays were developed and performed and children were prime participants in these activities. Zionist groups developed in many camps and Jewish schools. These groups provided family structure for children involved in them and encouraged a strong believe and Jewish identity (Dwork, 130). Some Jewish children were fully immersed in their Jewish culture, and they were able to develop an identity and grow within these beliefs. Hiding, ghettos and camps were most places of horror and a loss of childhood, but some children experienced lasting friendships and an immersion in Jewish culture and ideas.

Schooling was a daily activity that was sought after by many of the children throughout their circumstances. Jewish children were taken out of their normal homes and put into new circumstances with new routines and activities. One activity that was carried over from life before the war was the pursuit of education. It was an activity that many undertook even though it was illegal. One reason that education continued was that it was an attempt to provide hope to the children that life would continue after the war (Dwork, 120). Schools provided a chance to maintain what life had been like before the Nazi control of Jewish society. It was an important chance to maintain an aspect of childhood that had existed before the war. They could go about activities that were strongly connected to what life had been like outside of hiding, camps and ghettos and there was hope that life would continue normally after the war. It was an aspect of life that many pursued persistently even though it was a dangerous activity.

Some places were forced to deal with more restrictive laws, while some children were able to attend organized schools that ran exactly how they had before the Nazis came to power. In some ghettos education was a very dangerous enterprise to pursue, but many children continued to search for teachers and many teachers offered their time (Dwork, 180). Even those in hiding sought after books and attempted to continue their educations (Dwork, 75). Education was an important chance to provide hope and structure to these children. This attempt to provide a normal childhood helped those within these situations to bond with friends and provided hope that there was going to be a world where schooling would be important.

Children’s imaginations provided another escape and coping mechanism to deal with the extraordinary circumstances that Jewish children were placed in. Children were placed in conditions that were unexplainable and they were often forced into dealing with circumstances that would be difficult to deal with for anyone of any age (Dwork, 69). For these children, a fantasy world was developed in order to deal with the difficult situations they were in. Gerry Mok, who was placed in hiding at the age of five, stated that during his time in hiding he “lived partly in a dream world because you had to tell yourself constantly what it would be like later” (Dwork, 89). Mok tried to find comfort in what life would be like after the war. This was like the hope that schooling provided about life after war. For those children that were able to have some sort of freedom nature could provide another outlet for imagination. Jenny Portezky found that nature provided an escape from the world that she was living in and a getaway from what she was facing (Dwork, 90). Some children were able to find solace in their own minds. They could find peace and a different mentality than what was taking place in their own realities. Along with schooling, creating a fantasy world to help cope with what was taking place was a chance to maintain a “normal” childhood. These children tried to continue normal activities that they had participated in before the war in an attempt to maintain their childhood identity. However, the loss of identity and childhood happened with the large majority of children and this demonstrated how thorough and appalling the Nazi program towards the Jews was.

The attempts to maintain a semblance of childhood through schooling and imagination were not always successful. Loss of identity and childhood were prevalent among Jewish children in Europe. For those in hiding the loss of identity started immediately when files were destroyed, meaning that the child basically no longer legally existed (Dwork, 79). Those in hiding were meant to match what their foster parents expected of them and often felt shame and confusion about their Jewish identity (Dwork, 104). These children demonstrated that these events were nearly impossible for most children to comprehend. To some, it seemed that being Jewish was truly something to be ashamed of and that they truly were different. This shame seemed most apparent with children in hiding. Those within some ghettos and camps were surrounded completely by people who were like them. Jewish children were finally able to connect with each other and openly embrace their Jewish identity. There was some freedom in the ghettos (Dwork, 189). However, the loss of identity persisted throughout all other situations and it combined strongly with the Nazi attempt to dehumanize those Jews within the camps.

Upon entering slave labor and death camps Jews were told to forget their names and remember only their numbers (Dwork, 223). This transformation dehumanized many and took away their identity. Children within these camps faced an even harsher transition from children to slaves. Young children did not make it past the first selection within these camps, and were instantly killed. There was no attempt to create schools or a semblance of normal daily activities. The youth in this situation were expected to provide slave labor and made choices to adapt to that circumstance (Dwork, 217). Loss of any identity—whether it was their identity within a family or society or else their own childhood-- was an incredible difficulty that children of the Holocaust were forced to deal with. The Nazis sought a system of dehumanization and one way to achieve this was through starvation.

One of the most common fixtures for Jewish groups in Nazi Europe was hunger. Food was severely rationed within ghettos and camps; as well as difficult to come by when a child was in hiding. One of the major activities that children participated in was thinking and talking about food (Dwork, 74). Talking about food became a large part of the daily routine of children throughout Nazi Europe. In ghettos, games were even developed having to do with dealing with hunger; games like eating spit because it felt like eating food (Dwork, 142). The hunger was persistent and overwhelming. These children had to face severe situations in order to food. Many sought illegal measures such as smuggling and sneaking out of ghetto fences to game some food (Dwork, 199). Those children who were able to sneak out or smuggle successfully became the breadwinners of their families. Families no longer functioned under the same ideas and there were role reversals of what was expected of children. Children were not expected to play an incredibly important part in the survival of a family. These children were forced to give up their childhoods in order to survive.

Another difficulty having to do with hunger was the hard decision of how food should be rationed to communities. The question arose in some areas of whether children deserved more food and how to fairly distribute food amongst all (Dwork, 179). Hunger was a serious issue for children that had lasting impacts on their lives. Many children developed insecurities and hunger phobias that led to the problem of eating all food that was put down in front of them (Dwork, 140). Hunger sapped life force out of those suffering from it and acted as a dehumanizing factor (Dwork, 139). There was no strength left and many sicknesses developed because of it. Children were central to the debate about hunger because it was difficult to decide how food should be shared within societies. Hunger seemed to be the most prevalent and pervasive aspect of those Jewish Children who dealt firsthand with the Holocaust. Hunger was the issue that seemed to lead to the first stages of dehumanization and the development of other issues that came about.

This book provides a necessary link to explain the effects of the Holocaust. Children were completely innocent and their daily lives provide a vital window into the past. Dwork’s book demonstrates how complete the Nazi plans were able to influence daily life. These children, throughout all locations, found incredible ways to cope and adapt to the extreme nightmare they were placed in, but, ultimately, these Jewish children were forced to become adults and shed their identity to stay alive.

I certify that this essay is my own work, written for this course and not submitted for credit for any other course. All ideas and quotations that I have taken from other sources are properly credited to those sources. I agree to web publication of this essay.

EMILY WILLIAMS 3/18/10

|