|

Essay (back

to top)

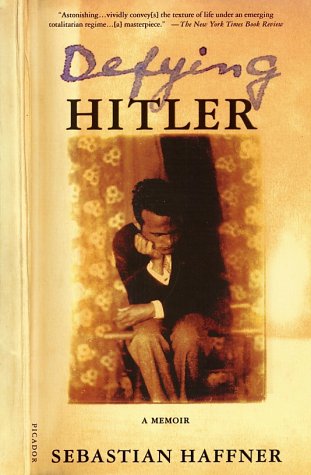

Sebastian Haffner’s Defying Hitler is a unique work in that it is a memoir written during the early stages of Nazism. Haffner, who while writing this work could not have known the outcome of Hitler’s regime, still gives a background with reasons for the rise of the Nazis, describing his early Nazi apprehension and anticipating their demise (only too early). Additionally, he gives his opinion of Germany’s politics at the time, and the affects all of this had on common Germans. What makes this perspective more genuine is the fact that he comes from a middle class family, is well educated, was well liked among his peers, and obtains a position in the courthouse, all the while socializing with Jewish people, later dating Jewish women (and post memoir marries a Jewish woman). Haffner poses and answers questions regarding: how World War I led to Germany’s war fanaticism, antisemitism, and rise of nationalism, how Germans allowed unjust acts to be carried out against political dissidents, and what would lead to the eventual annihilation of most European Jews (which Haffner does not address as a question, but answers in his description of the aforementioned events). In all of this he warns readers of: the dangers of nationalism when it becomes fanatical, the effects of mob mentality, silence against one’s better judgment, and being naïve about one’s government and society. Most interesting is the fact that his many small acts of nonconformity in daily life were the defiance, not any particular heroic act to speak of. Though Haffner fails to commit any obvious public act, his resistance is blatant enough to call defiance because of his violation of major German laws, such as: courting a Jewish person, opposing the Nazi regime, and assisting Jewish people; all of these transgressions were punishable by death.

To begin with, Haffner gives readers his own German background, growing up around the start of WWI. He reasons that giving his own experiences during this war as a child, and how he and his family were hardly affected, offers an accurate portrayal of how most Germans experienced this war. Because none of the war was fought on German land, its citizens were forced to accept whatever information the media provided them, “As the war took place somewhere in distant France, in an unreal world, from which the army bulletins appeared like messages from ‘the beyond,’ its end also had no reality for me. Nothing changed in my immediate, physical surroundings” (Haffner 25). As a child, he closely followed war death counts, prisoners, and battles won, and likewise formed war games with his schoolmates modeling what they had learned to idolize. It seems that the after war effects made a greater impression on Germans, including Haffner. Most everyone met the start of the war with enthusiasm, and bore trials that came with it believing their government’s insinuation of impending victory, only to discover the dark truth afterwards. He states, “From 1914 to 1918 a generation of German schoolboys daily experienced war as a great, thrilling, enthralling game between nations, which provided far more excitement and emotional satisfaction than anything peace could offer; and that has now become the underlying vision of Nazism” (Haffner 17). Germany would have to surrender and in surrendering accept a peace treaty that would make its economy dependent on a comparably young nation, the United States.

Haffner turns his war-game reality into a coming of age analogy regarding its transference into youth fanaticism in any new realm, starting with sports. He shares that although the government thought at the time that sports were an excellent distraction from the war time of the past, this was really just transference of fascination. If anything, sports just continued their over enthusiasm, which would later have a political focus. Once politics came into play, with the rise of the German Revolution, the changing of Reich rulers, and later the prominence of Hitler and his Nazi ideology, German youth had to decide if they were more ‘right’ or ’left’ and dealt with the consequences accordingly. He explains, “At that time I had no strong political views. I even found it difficult to decide whether I was ‘right’ or ‘left,’ to use the most general political categories. In day-to-day politics I formed my views according to the circumstances; sometimes I had no view at all” (Haffner 103). Though Haffner is unsure of his political ideology in his early twenties, he considers himself more ‘right’. Later he finds that the ruling party does not at all demonstrate what he feels, and he expresses his disagreement, although not at a social level obvious enough to get him into trouble.

Along the way, Haffner discusses the youth in the generation before him who dealt with the post war economy in a very new way. After the war, during times of inflation, people relied on their investment in shares while the value of the mark plunged daily. The generation before him became very wealthy and took high positions in banks while his father relied on old tradition and his family suffered poverty. As the value of the mark came back up, things went back as they were before, and the classes repositioned with the older generation back in the upper/middle class. This foreshadows the flexibility of the German state, and what can come of a changing economy, and a change in government. Germany changed radically from its traditional operation, and adopted new radical laws and practices once Hitler became Chancellor.

Heinrich Bruning, an unpopular German ruler who dealt with the German people without empathy, was the Chancellor before Hitler. In times of struggle he suggested that they “tighten their belts” (Haffner 85) rather than creating any sort of reform. In the Bruning era, the rights of Germans began to disappear, an ideology Hitler later adopted. Haffner writes, “Many of Hitler’s most effective instruments of torture were first introduced by Bruning—such as “safeguarding foreign reserves,” which made travel abroad impossible, and the “Reich flight tax,” which did the same for emigration” (Haffner 86). Unlike Hitler, however, Bruning thought that he was protecting the state as a whole. Later, as Hitler gets democratically elected (though one may argue that the way by which he was elected was neither honest, nor democratic) Haffner finds a change among the German people. Not only were the remnants of the Bruning era lingering behind, but additionally, the Jews were targeted as a group and they were deprived of more rights. Being one who had Jewish friends, a Jewish girlfriend, and was immediately opposed to the Nazis, Haffner was against this.

Like many Germans of the time, Haffner and his father thought that the Nazis would not last. They believed that this radical group would end just as soon as they had started, “I was inclined not to take them very seriously—a common attitude among their inexperienced opponents, which helped them a lot, and still helps them” (Haffner 104). The Nazis started out not just abusing Jewish people, but interning political dissidents. Anyone with any influence, from doctors to politicians who did not side with Hitler’s party, was first boycotted and later taken to internment camps. As all of these things happened gradually, many people (who were not immediately affected) ignored them, or truly did not notice them. Assuming that this group (Nazis) is not much of a threat, when the pre-Nuremberg laws were imposed, Haffner was caught off guard.

First, Haffner had to realize not only that Hitler had aligned the state against dissidents, and all Jews, he also had to realize that Hitler had aligned him with them. Why? Haffner notes that he was considered Aryan and not only displayed very Nordic facial characteristics, but also had not had any Jewish blood within the family line for at least 200 years. In this identity, he also had to accept that some Jews who were being persecuted by Germans looked at him and saw him as a Nazi, or a Nazi supporter. This includes his friend Frank’s father who treats him as a Nazi for no other reason than his appearance and racial categorization. For Haffner this is very difficult since he had been against the Nazi party from the start. At one point, when Jewish lawyers and other Jewish legal representatives were being thrown out of the courthouse he worked in, an SA man came up to Haffner and asked if he was Aryan, he replied “yes” and immediately felt immense guilt. In not proclaiming his defiance, he feels guilt by default. Haffner was aware that his only choice was to do what he could for his friends, and get out of Germany; public defiance would only result in his demise.

As the Nazis gained power, the rights of Jewish people were taken away immediately. First, Jewish people were fired from all businesses, then their own businesses were taken away from them and they had to pay Aryan Germans to take them over. One thing after another led to the necessity for Jews to leave Germany, only laws already in place stopped many of them from doing so. In one instance, Haffner’s friend Frank’s ex-girlfriend was unable to emigrate because she could not get a passport as a result of her father’s national obscurity. This is not to mention a number of German Jews whose financial stability was planted in Germany, if they could not afford to leave, or did not have the resources to do so.

As Haffner and his family did not believe that Jewish people were inferior, it was hard for him to deal with what was to ensue, mass chaos. Once Haffner realized the intensity of new German practices, he became worried about his girlfriend, Charlie, and his other Jewish friends. After making sure to take care of Charlie (offering her refuge in his home) and later helping his friend Frank and his fiancée, he is later forced to join a Nazi organization (the SA) because he is a German lawyer just finishing his schooling, forcing him to bear the swastika among other things. Thankfully, though Haffner mourns his own fate, for the time being Charlie is safe, and Frank and his girlfriend are able to escape to Switzerland. Though joining the SA goes against everything he believes in, Haffner accepts his duty and joins. Immediately upon release, he flees to England where he is more at liberty to express his views and live life. Here the memoir ends.

It is slightly disappointing that the book ended abruptly, but being that Haffner never meant for it to be published, and his son published it after he passed away, it is to be expected. It was a very fulfilling memoir, in that it gave me insight into what may have been the opinion of many Germans. Not every German was a Nazi or a radical helping Jewish people in their countries; many people were complacent in many ways, but helped in ways that would make a difference to them. Also, many Germans like Haffner may have continued to have relationships with Jewish people without allowing fear to stop them. It is also refreshing to see the perspective of a German before the start of the Holocaust, and how this affected average Germans. I really enjoyed the memoir and the author’s willingness to express his thoughts about Jewish people and especially about the Nazis despite what appeared to be popular opinion. Maybe his opinion was actually that of a majority, everyone was just too afraid to say so, and we all know the unfortunate result of that.

Though the memoir provides an honest firsthand account of the experiences of an Aryan German in Nazi Germany, and the moral dilemmas he faced, its proclamation of defiance is debatable. Haffner’s aforementioned small acts of nonconformity in daily life, though dangerous with regard to the Nazi regime, did little for the greater Jewish community. Respecting the fact that many Germans risked their lives to protect and save their Jewish community members, their resistance stopped short of liberating the population. The silent majority could have stopped the Holocaust, but their collective submission or inaction forced others to hide their opinions and threatened their safety when trying to help the oppressed. A public, united defiance would have stopped the Holocaust before it started, though one must consider Germany’s state of vulnerability and human being’s susceptibility to the bystander effect and mob mentality. Although the Holocaust cannot be undone, contemplating what allowed it to happen will prevent future events of its nature.

|