|

Essay (back

to top)

To say that unspeakable tragedies occurred during World War II and the Holocaust is a gross understatement. The abrupt and horrific means in which millions of lives were exterminated, be it on the battlefield or in a concentration camp, laid waste to the claim of the advancement of civilization and made the face of humanity indistinguishable from that of the basest form of cruel beasts. Yet, despite every atrocity that occurred in the hell into which the world was plunged during those dark years, none was greater than the loss of the innocence that was stolen from the children caught in this unimaginable nightmare. Childhood is one of life’s greatest and simplest treasures, the only time when one is completely free from the troubles and vileness of the surrounding world. To take that away, to destroy it utterly and completely, is one of the most wicked crimes in human history.

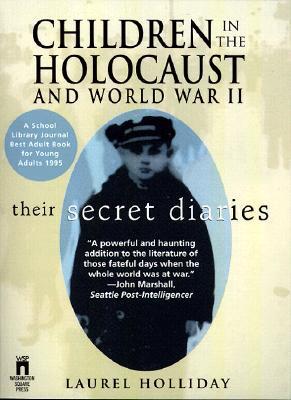

As a testament to the plight of children living in the midst of World War II, Laurel Holliday’s book, Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries, submerges readers into the lives of 23 youngsters whose experiences are preserved in the pages of their letters and diaries. Before beginning the journey into over 400 pages of first-hand, source accounts, Holliday introduces some central questions to consider when reading the stories. First, she asks why children not only bothered, but persisted, in keeping diaries despite the physical and psychological difficulties associated with doing so for such long durations throughout the war. Then, she poses the question of how children “experience and survive trauma” (Holliday, xvii). In addition, the children’s writings answer questions about the routines of everyday life in Jewish ghettos, Nazi concentration camps, and war-torn Europe. Through the various stories from boys and girls in ages ranging from ten to eighteen, Holliday presents her compilation as evidence for a more encompassing perspective of adolescent life than can be found in only a single, famous account like that of The Diary of Anne Frank. The imposed forsakenness of childhood is a bridging theme connecting the different experiences; and it is through the acceptance of their cruel reality, their expressions of compassion, and their forced contemplation of death, where readers can see that these children experienced life in a means far beyond their years.

While Holliday’s book does offer a broad variety of experiences and emotions from children all over Europe, some may find that this anthology still does not give a well-rounded picture of average childhood life during this time. To be sure, not all children kept diaries. In fact, in most instances it was difficult and life-threatening to produce any writing at all. In her introduction, Holliday states:

To write as frequently and as much as these children wrote was no simple matter. To begin with, they needed to find materials for writing. Pens and paper were difficult to obtain in the concentration camps and ghettos. Those children who were under Nazi guard also needed to find a place where they would not be observed writing. And once they had written their stories, the children had to find suitable hiding places for their work so that it would not be confiscated during Gestapo searches (Holliday, xiv-xv).

It would seem that these children who did persist in their writing were already one step ahead of the other children around them. It may be that they all had extraordinary qualities of extra determination, stronger willpower and discipline, or a greater degree of literacy that distinguished them from their other youthful counterparts who also suffered in the war. It could be argued that instead of providing a more encompassing picture of the youth at this time, the book merely provides another picture of other extraordinary circumstances not necessarily applicable to lives of all of the children in the Holocaust or World War II.

To this claim, I give partial validity. It is true that the cases presented in Holliday’s book are all extraordinary cases--each in their own right; but every story, known or not, is extraordinary. But many children did keep diaries during the war, and it is impossible to know how many are lost forever. In addition, the book does a great, albeit imperfect, job of providing a more holistic picture of the various situations in which children could find themselves during this time. Holliday includes entries from fourteen girls and nine boys spread throughout ten European countries: Poland, Holland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Lithuania, Russia, Belguim, Denmark, and England. In addition, readers receive the perspective of both Jewish and non-Jewish children. It is safe to assume that if common themes and recurring topics are found within the diaries of children in such diverse situations, there are most likely other children whose accounts were very similar, if not almost identical, to those situations presented in this book. At the very least, readers get the description of everyday life in ghettos, concentration camps, and war-torn Europe that can be applied to the lives of not only other children, but to many of the Holocaust and war victims, regardless of age.

One of the most striking features throughout all of the entries is the way in which the diaries and the process of writing helped these children to maintain their sanity and accept the reality of all that was occurring around them. The youngest of the authors, ten-year old Janine Phillips, recounts her life after the Germans took over Poland. Although so young, Janine had a mastery of latest news from the front and dutifully reported in her diary all that she and her family were doing to prepare for the war. When asked to help dig a trench for their bomb shelter, Janine said:

Being next to Aunt Aniela, I could see that she is not a digger. Every time I dug a hole, she filled it in...[Then, Uncle Tadeusz] wanted to know whether Aunt Aniela and I were, by any chance, digging for worms. I said that I was not, but Aunt Aniela said that she would much rather dig for worms than for Uncle Tadeusz (Phillips-10, 6).

Janine’s diary shows a perfect example of childlike qualities blending with the adult duties that were asked of children, such as physical labor. Even though she worked all day to build a bomb shelter in an attempt to escape the violence that falls nightly from the sky, she found a way to incorporate a sense of humor in executing the tasks that she was not fond of doing. Using her diary as an outlet, she was able to ask questions and express her frustrations when she couldn not openly talk to others around her.

Another example of a critical realization and internal introspection comes from Moshe Flinker, a thirteen-year old Jewish boy whose family fled to Belgium. In one of Moshe’s entries, he expressed his complete frustration with other youths who were not empathizing with the plight of others:

What are the spiritual values of these boys and girls, who may well be regarded as a typical high-school youth. While such terrible events are going on, while millions of young people are being plucked in the bud, while millions more risk their lives for the sake of ideas, whether correct or distorted but at least with the honest and consecrated intention of ensuring the world a better future - at the same time these boys and girls sit here and by their expressions you would never guess that anything had happened in the world or that lawlessness and violence are the order of the day. Shallow youth, with neither ideas or ideals, without any kind of content whatever, really completely worthless (Flinker-13, 268).

Not only did he show a deep understanding and connection to the seriousness of the tragedies of the Holocaust and the war, but he was critical of others for not showing the proper amount of reserve and respect that he felt the situation deserved. Even more so, Moshe went so far as to distinguish himself from this “worthless youth” and spoke about them with the condescending manner of an embittered elderly man. It is interesting to note though, that just a few moments later, when the other children asked his name, he offered a false “safe” name. Immediately, he revealed his regret saying, “They served as a standard to which I had tried to adjust my own values” (Flinker-13, 268). Throughout his diary, Moshe seems to have a strong awareness of his emotions and perceptions. Despite the fact that his family could be arrested--and they eventually were killed in Auschwitz--he realized that he must focus on things that would work to better the moment; although, he still continued to articulate the confusion that he felt:

So now all day long I do nothing but search for some positive content for my life, so as not to be entirely lost. In every single thing I hope to find a meaning which will fill me and satisfy me...I am lost and seek in vain, for meaning, for control, for purpose (Flinker-13, 269).

For Moshe, the time had come to grow up and put childhood things behind. Instead of living in carefree innocence, he focused on finding meaning in the life he knew could have very limited time left.

On a similar note, while there are varying processes of realization and acceptance in the different stories , there is a general consensus amongst the children that expresses frustration at the helplessness of the victims and demonstrates a strong will to survive. Charlotte Veresoa, a fourteen-year old child of “mixed blood,” was deported to a youth barracks in Terezín. When word reached that the Nazis were selecting children to be taken to the gas chambers, Charlotte said:

But I won’t give up. I am not a bug, even though I am just as helpless. If something starts, I’ll run away. At least I’ll try, after all, what could I lose. It would be better to be shot while trying to escape than to be smothered with gas (Veresova-14, 206).

Yitskhok Rudashevki, trapped in the Vilna ghetto in Lithuania, expressed a similar sentiment when he talked about saving his life at all cost, so as to refute the “point of view of our dying passively like sheep, unconsciousness of our tragic fragmentation, our helplessness”

(Rudashevki-14, 152). In Warsaw, fifteen-year old Mary Berg acknowledged the ability of those trapped in the ghetto to overcome the desire to commit suicide. After noticing that the thousands of lives around her were being exterminated like “sheep in a slaughterhouse,” she said :

It is inconceivable that we have the strength to live through it. The Germans are surprised that the Jews in the ghetto do not commit mass suicide...We, too, are surprised that we have managed to endure all these torments. This is the miracle of the ghetto (Berg-15, 229).

Indeed, many different stories show how the children and others around them are determined to endure tremendous burdens and grief. Most children express their desire for freedom to enjoy the simple pleasures in life, like playing in the snow. Even when all else seems to be lost, almost all of the stories call for a struggle to continue forward. After discovering the loss of her entire family, Tamarah Lazerson looks for a greater purpose saying, “I must fortify myself with strength and patience and pave a new road for myself to the future” (Lazerson-13, 135). These children conveyed an appreciation for life that most adults, let alone children, struggle to discover in a lifetime. The harsh inhumanity of the Holocaust and the war forced them to face reality in a pragmatic and critical way, and playtime was replaced with duties that meant the difference between life and death.

Even though each child faced a set of dangers that threatened their own lives, there is an overwhelming sense of compassion that flows from their writings and actions. Mary Berg, who was lucky enough to escape from the Warsaw ghetto to the United States because of her American citizenship, wrote this upon her arrival in New York:

I shall do everything I can to save those who can still be saved, and to avenge those who were so bitterly humiliated in their last moments. And those who were ground into ash, I shall always see them alive. I will tell, I will tell everything, about our sufferings and our struggles and the slaughter of our dearest, and I will demand punishment for the German murderers and their Gretchens in Berlin, Munich, and Nuremberg who enjoyed the fruits of murder, and are still wearing the clothes and shoes of the martyrized people(Berg-15, 248).

Mary did not focus on herself or even rejoice when she reaches safety. Her first thought was for all of those who were left behind, and her profound words show maturity, grace, and a sincere concern for others. The anthology continues to show that even the smallest of children were capable of demonstrating large acts of kindness in their own unique manifestations, as Dirk Van der Heide, twelve, described when his little sister came across another lonely, young girl: “I forgot to say how nice Keetje was before we left Dordrecht. She gave her big doll, Dopfer, to the little girl. Keetje was nice to do this. She is often very selfish but she is good to do this” (Van der Heide-12, 44). In a time when conflict made looking after oneself the most pragmatic thing to do, these children were unselfish and gave more than most children in normal circumstances would have, both emotionally and physically.

The most beautiful testament of compassion within the anthology comes fromKim Malthe-Bruun, an eighteen-year old Danish boy who joined the partisan underground in 1944. He was captured and sentenced to death in 1945, and the following are excerpts from his letter to his love, Hanne:

My own little darling,

Today I was taken before the military tribunal and condemned to death. What a terrible blow this is for a girl of twenty!...What do I possess that I can leave you as a parting gift so that in spite of your loss you will smile and go on living and developing?...Don’t let [my death] blind you and keep you from seeing all the wonderful things life has in store for you...All of us are going to die and it isn’t for us to judge wheather my going a little earlier is good or bad...The truth is that after suffering comes maturity and after this maturity the fruits are gathered...I would like to breathe into you all the life that is in me so that it can go on and as little as possible of it can go to waste. This is the way I was made.

Yours, but not for always (Malthe-Bruun-18, 362-365).

This moving letter shows not only his bravery when confronting death, but moreover his sense of concern for the way that it would affect his dearest love. His words, his advice, and his unending love are uncharacteristic for someone of his age, while his strength and positive outlook on life are quite remarkable and deeply compelling.

Even in their reflections on death, the children’s writings show a profound and rather brave grasp on what most people cannot bear to contemplate. Tamarah Lazerson, a thirteen-year old Jewish girl who was separated from her parents after the ghetto of Kovno was burned down, said this after seeing a friend, “beautiful and blooming, suddenly cut off by death”:

The ground will welcome you, the tired, to her bosom. The heavens will let fall, at the very least, a tear - and thus your life will end. Why sink into despair? Why mourn? Why love and hate? No need! Manifestly we are but withered grass in the parched fields of life (Lazerson-13, 133).

Ina Kanstantinova, in the midst of the German attack on Russia, wrote this on her sixteenth birthday:

On the last day of my childhood:

It is painful to give up all that is close and dear to us, especially one’s childhood. I know one thing: the joys of childhood-are gone forever. Good-bye my morning. My day, bright, but exhausting has begun. And there, at the end, by old age awaits me. But will I reach it?...Good-bye childhood...forever (Kanstantinova-16, 251).

Death is not a concept meant for children to have to consider; and while these writings express great sorrow, they convey a sense of acceptance and an acknowledgment of inevitability that is quite surprising from people who were so young.

Overall, Laurel Holliday’s book is a powerful addition to the literature on the tragedies of the Holocaust and WWII and provides a valuable insight into the lives and circumstances of the youngest and most innocent victims. When reading such profound sentiments and moving experiences, it is amazing to think that the accounts were all written by children instead of more experienced adults. Even the eloquence in their words deceives readers of their years, and it is always a slight shock to be reminded of their age. Despite their youth, these children were hardly children at all. When faced with the cruelties of the Holocaust and war, they were still able to show unselfish compassion even in the face of death. These stories and these lives, along with millions of others that will never be known, are a reminder that life is what one makes of it, regardless of the time one has or the situation in which one is placed. Hannah Senesh, a seventeen-year old who volunteered with the English partisan underground to help save the lives of her fellow Eastern European Jews, asks this in her diary: “Why is it necessary to ruin the world, turn it topsy-turvy, when everything could be so pleasant? Or is that impossible? Is it contrary to the nature of man” (Sensesh-17, 313)? The answer is no, Hannah. You and the other children have proven that amongst evil, goodness exists. We will never forget your stories, and your voices will never go unheard.

|