|

Essay (back

to top)

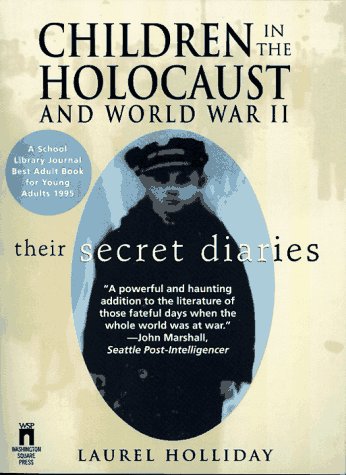

World War II took away the common experiences and opportunities for children. It robbed them of their childhood, and they were neglected from education, family relationships, and play. Some estimates claim that 1.5 million children were murdered during the Holocaust. Just because they were children did not mean they were not targets of violence and did not undergo the cruelty and pain of the war. Surviving diaries provide horrific first-hand accounts, and serve as a way to learn about the children’s lives during wartime. Laurel Holliday’s book, Children In The Holocaust And World War II: Their Secret Diaries, gives readers the opportunity to look into the chilling lives of children who have left a powerful legacy behind. The diary entries of the 23 children showcase that whether living in ghettos, being sent to concentration camps, or being confined to hiding, their positive adolescent experiences of childhood were replaced with horrifying encounters of brutality, and feelings of despair and isolation. Most of them wrote in their diaries for their own self-expression as a means of coping, and to tell the world how important human freedom is.

When one thinks of children in the Holocaust, Anne Frank usually comes to mind. The famous diary she kept while in hiding has shown the world only one perspective of the hardships and innermost thoughts of children during World War II. Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries is the first collection of diary entries of children from the Holocaust. From children living all across Europe, we learn about their startling thoughts and encounters during wartime Before each child’s journal entry, Holliday provides a brief summary that includes their name, place of origin, age, family information, and whether or not they survived.

Children should have dreams and aspirations; they should be excited for their future and work hard for their goals, yet children living in Europe during World War II had a different outlook on life. In many of these writings, children expressed feelings of despair. They lost hope as they witnessed cruelty and lived in constant fear due to their Jewish heritage. Something so trivial in today’s society had caused them to wish for death. Sarah Fishkin was a seventeen year old who lost “hopes and dreams of the Jews.” (Holliday, 335) Her family was broken apart when the Nazis buried her younger brother and sister alive in a pit, and her father and older brother were sent away to a different death camp from her. She wrote:

All thoughts of staying alive become shrouded in great sadness. I feel in my heart the desire to perish together with my family, to end my young life beside my parents… How much more cheerful can one’s heart grow when we are commanded to leave the place where we are and the same kind of end awaits everyone… I must give up forever my thoughts of future goals and the fantasies I hoped to see. Emptiness and desolation, saddened aching hearts, are our present constant companions. There seems to be no future for the Jewish population. (Holliday, 337-338)

Sarah’s outlet for expressing her feelings was her diary. She used her diary in attempt to express her feelings about Jews and their future. Their lack of freedom and rights have led her to want end her life. Through the disarray of losing her family, she articulated her emotions the best way she was able to under her circumstances.

Another account of desolation and hopelessness is by an anonymous boy and his sister. He wrote, “My little sister complains of losing the will to live. How tragic. She is only twelve years! We are so tired of ‘life’. I was talking with my little sister of twelve and she told me: ‘I am very tired of this life. A quick death would be a relief for us.’ O World! O World! Truly, humanity has not progressed very far from the cave of the wild beast.” (Holliday, 400) Their childhood activities, and future dreams are replaced with the knowledge that today could be their last.

Eva Heyman, a thirteen year old who lived with her family in Hungary, often foretold her own death. Her best friend had been shot and killed by the Nazis and Eva was convinced that they would murder her too, no matter how much she wanted to live. She wrote how she always dreamt about her friend Marta who died:

I don’t think much about Marta, but yesterday I dreamt that I was Marta and I stood in a big field, bigger than any I had ever seen, and then I realized that that field was Poland. There wasn’t a sign of a human being anywhere, or of a bird, or any other creature, and it was still, like that time we were waiting to be taken to the Ghetto. In my dream I was very frightened by the silence and I started running. Suddenly, that cross-eyed gendarme grabbed me from behind by the neck, and put his pistol against my nape. The pistol felt very cold. I wanted to scream, but not a sound came out of my throat. I woke up and it suddenly occurred to me that that is the way poor Marta must of felt at the moment the Germans shot her to death! (Holliday, 121)

Children were in a state of misery and their writings convey that even as children with youthful innocence they could not dream and hope about survival and freedom. Although it is not certain if all children wrote in their diaries for themselves or for future historical references, but people should be grateful for these diaries as they provide great historical facts and information about the anguish children underwent, and share with the world the terror of their situation. Optimism was something individuals have to dig deep inside themselves for; it was extremely difficult for these children to find it while their dreams and future were replaced with pain and oppression while enduring the effects of war. The Holocaust robbed children of their childhood, thus forcing them to struggle with death and loneliness.

Despair is not a difficult emotion to feel when a child undergoes beatings, and witnesses family members or even strangers dying. No matter where one was located in Europe during World War II, torture and slaughter were extremely common. As these diary entries serve as a startling first-hand account, readers are provided with chilling images and cannot help but feel extreme sorrow for what these children experienced. The most poignant entry of brutality was written by a girl named Macha Rolnikas. She was fourteen years old and grew up in Lithuania. Her diary entries were written while she was in the ghetto, as well as in Stutthof concentration camp. While at the concentration camp, Macha was ordered to undress the dead and pull out their gold teeth. In her entry she wrote that a dead woman was lying at her feet, and with a shaking hand she cut the dress, but the corpse fell backwards and knocked against the floorboards. In her mouth she saw gold teeth but could not get her self to pull them out. She quickly closed the mouth and as a result the supervisor yelled, “You silly fool, what are you doing? She starts hitting me with a club. She always aims for my head. It seems as if my skull is splitting in. And she doesn’t stop. There is blood all over the floor. She beat me until she herself was out of breath.” (Holliday, 196) There were no other options when one disobeyed the rules; the result was abuse. Macha later wrote, “In order to feel my powerlessness a bit less and not to think of torture that is caused by each step, I go on mentally writing in my journal.” (Holliday, 197) To clear her head and find as much comfort as she possibly could, she poured her emotions out on paper. As a child experiencing the type of dehumanization that Macha did, it was vital that one was able to express their feelings as a way to cope.

While Macha experienced first hand brutality, Mary Berg, a fifteen year old with American citizenship living in Poland, witnessed horrors of friends, family, and neighbors in the Warsaw Ghetto. Macha described how “Warsaw looked like an enormous cemetery.” (Holliday, 218) She looked out her window and observed revolting incidents such as:

A man with markedly Semitic features was standing quietly on the sidewalk near the curb. A uniformed German approached him and apparently gave him an unreasonable order…Then a few other uniformed Germans came upon the scene and began to beat their victim with rubber truncheons. They called a cab and tried to push him into it, but he resisted vigorously. The Germans then tied his legs together with a rope, attached the end of the rope to the cab from behind, and ordered the driver to start. The unfortunate man’s face struck the sharp stones of the pavement, dyeing them red with blood. Then the cab vanished down the street. (Holliday, 220)

While living under Nazi persecution, it is evident that youths revealed atrocities and unimaginable horrors. No matter what type of torture one experiences, a child, especially, cannot emotionally understand it at such a young age. They needed an outlet to convey their emotions they felt from experiencing or witnessing these gruesome and appalling actions, and in doing so they transmitted them to their diary.

Although people in hiding probably never witnessed abuse of other people, hiding was not a simple solution to the war, and for some children it was actually ann indirect form of brutality by the Nazis. Ephraim Shtenkler was forced to live in a cupboard from the age of two to seven. Before Ephraim was saved, he was “hidden in a cabinet where he was unable to even stand up, his feet were twisted backwards and it took months of medical treatment before he was finally able to learn to walk at age seven.” (Holliday, 21) At eleven years old Ephraim wrote about his experiences, and they were later published in a Jewish magazine. Hiding lasted for years and came with the lack of human interaction. He wrote that he “lay either in the cupboard or under the bed…and one day the elder daughter [of the family who was hiding him] had gone to play outside and I wanted to cry, for I envied her. It was already three to four years that I hadn’t gone out of the doors.” (Holliday, 25) The war made some children grow up hiding thus not allowing them to experience daily events such as attending school or socializing with children of their age. Childhood activities were replaced with boredom and pain. Ephraim’s story, although written after he was saved, still portrays the childhood experiences that were deprived from him. Writing his memories four years after he was saved was still a way for the young Ephraim to find meaning of his experience during the war, and to share with the world his experience, and the importance of freedom.

When a child was sent to a concentration camp, the ghetto, or confined to hiding, often times they were physically as well as emotionally separated from their loved ones. When experiencing isolation, these entries demonstrate that they turned to their diary as a friend whom they were able to share all of their thoughts, ideas, and emotions with. Evan Heyman constantly wrote in her journal as though her diary was a person. For example, in the middle of an entry she addressed the diary and wrote, “Dear diary, I’m taking you along to Aniko’s house. Don’t worry, you won’t be alone; you’re my best friend,” and when Aniko left Evan, she wrote “I’m so sorry that she is leaving us.” (Holliday, 103) Social interactions are an essential part of a child’s life experiences and mental development, and by creating her diary as her best friend it was a way of coping with her experience of loneliness and isolation

Through years of hardships from the war, Eva had turned to her diary to express her emotions and conveyed her fear of dying multiple times. She wrote to her “best friend,” “Dear diary, until now I didn’t want to write about this in you because I tried to put it out of my mind, but ever since the Germans are here, all I think about is Marta. She was also a girl, and still the Germans killed her. But I don’t want them to kill me! ... I don’t want to die, because I’ve hardly lived.” (Holliday, 101) Evident from previous diary entries from Sarah and the anonymous boy, children were writing their thoughts about death. Writing down their emotions served as a coping mechanism, well as a way of self-expression. Many used it as mental strength to survive another day, while others used it to discover that they rather leave the world they were in and join their family members and friends who had already passed on.

These legacies that children left behind are a powerful collection of horrific first-hand accounts from a child’s perspective. Compared to the conditions that adults were forced into, not a lot of information is known about the lives and treatment of children during the Holocaust. These diaries provide another dimension to the suffering that a specific group of individuals underwent. The deprivation of childhood experiences that were replaced with brutality, isolation, and despair, led the youth to write and use their diaries as an outlet to express their emotions as a means of coping. Not only did expressing their feelings on paper aid children with loneliness, gain the courage to live another day, or help them learn about their desire to rather end their own life, but these diaries have been a major addition to the literature of World War II which will continue to educate future generations.

Works Cited

Holliday, Laurel. Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries. New York: Washington Square Press, 1996.

|