|

Essay (back

to top)

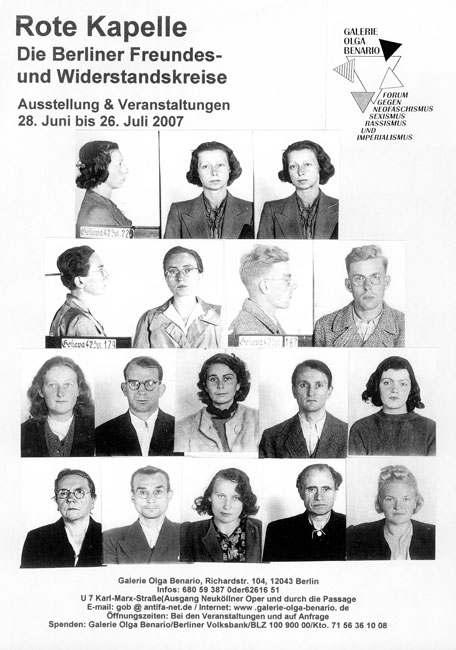

The Second World War was a devastating conflict that touched everyone; from soldiers on the battlefield to families at home. It is natural, then, that this war took place on many fronts. Internal resistance was an important factor in defeating the Nazi regime. Partisan fighters helped weaken the Third Reich from the inside both by using force and by sharing intelligence with Allied powers. One such resistance group came to be known as the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack circle, or by the Gestapo as the Berlin Red Orchestra. Their anti-Nazi efforts included encouraging domestic dissent and sharing intelligence information with foreign powers. Ensuring that their intelligence information was fully utilized, however, was not easy for the Red Orchestra. For all the important work these resistance fighters did, and for all the risks they took, relatively little is known about the Berlin Red Orchestra. Foreign governments were often distrustful of the members of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group for various reasons including Nazi party membership and secret political leanings, as well as foreign disinterest in their information. Furthermore, his group is so under-acknowledged because the majority of its members were executed by the Nazis for their espionage work, and competing political ideologies in post-war Germany often came into conflict with the group’s internal beliefs.

The Red Orchestra, or Rote Kapelle in German, was the Gestapo’s code name for three independent anti-fascist resistance groups. Two of the groups worked closely with the Soviet government. The third, often called the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack circle after some of its key players, was based in Berlin. Although often categorized as communist, the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group was in fact a diverse mix of anti-fascist activists. The group started when longtime friends Arvid and Mildred Harnack and Adam and Greta Kuckhoff began relaying intelligence to Allied officials. Through various connections they met Harro Schulze-Boysen and his wife Libertas. These three couples formed the core of the Red Orchestra in Berlin. They gradually brought other trusted anti-fascists into their circle. The group grew to include people from all political backgrounds and from every station of life. In addition to supplying the Allied powers with intelligence reports, the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group tried to agitate for overthrow of the Nazi regime from within Germany. They printed and dispersed leaflets, carried out sticker-posting campaigns, and helped Jews escape death at the hands of Nazis.

Arvid Harnack was one of the founders of the Berlin Red Orchestra circle. Arvid was an economist who had studied at the University of Wisconsin as a Rockefeller Fellow in the 1920s. In Madison Harnack met his wife, Mildred, and later Greta Kuckhoff. After returning to Germany he continued his studies and later became a lecturer at the University of Berlin. To Arvid, the Great Depression demonstrated capitalism’s failure. He began to adopt more socialist and communist views, culminating in a visit to the Soviet Union in the 1930s. After Hitler came to power Arvid deemed it necessary to join the Nazi party himself to increase his employment prospects and to divert attention away from him. Being inconspicuous was important because Arvid had begun to relay Nazi intelligence to the Soviets via the Soviet embassy in Berlin. Arvid was repulsed by the fascist policies of the Nazi party and considered it his patriotic duty as a German to resist Nazi power. Arvid made contacts at the American Embassy through First Secretary Donald Heath, and at the Soviet Embassy primarily through agent Korotkov. By sharing information with these foreign powers, Harnack hoped to bring an end to the Nazi regime as soon as possible. He firmly believed that “both the Soviets and the West were required to ensure a victory over the Nazis, and that he could be, a bridge between the United States and the Soviet Union” (Nelson, 160).

Mildred Harnack, née Fish, was the American wife of Arvid Harnack. After following her husband to Germany in the late 1920s she continued her studies at the University of Giessen and later the University of Berlin. She was also a lecturer, translator, and literary historian. Like her husband, Mildred became attracted to socialist and communist ideas following the Great Depression. Also like her husband, Mildred morally opposed the policies of the Nazis. She helped print, translate, and distribute anti-Nazi fliers. She also helped her husband make contact with Soviet agents and assisted in relaying important intelligence information to these agents. Perhaps Mildred’s most significant contribution to the Berlin Red Orchestra were the connections she made between members of the group. Thanks to Mildred’s connections at the American Embassy in Berlin Arvid was able to make an intelligence connection with the first secretary Donald Heath. More importantly, the Harnacks connected with the Schulze-Boysens and others with whom they were able to share information and promote domestic resistance against the Nazis.

Adam and Greta Kuckhoff were two other founding members of the Berlin Red Orchestra. Like the Harnacks, the Kuckhoffs were morally opposed to Nazi policies. Adam was a German writer and journalist. He was moved to take more direct action against the Nazi regime by the murder of his friend Hans Otto, a dedicated anti-fascist. Adam Kuckhoff helped the anti-Nazi resistance movement by helping facilitate the exchange of intelligence to foreign powers, specifically the Soviet Union, and by spreading anti-Nazi propaganda from within Germany.

Greta Kuckhoff, Adam Kuckhoff’s wife, was one of the few surviving members of the Berlin Red Orchestra. She facilitated contact between her husband Adam and the Harnacks, whom she had met while studying in Madison, Wisconsin. Greta took a less active role in the Red Orchestra to protect her and Adam’s young son Ule. She contributed to the Red Orchestra by helping produce anti-Nazi propaganda and helping her husband make intelligence contacts.

The Schulze-Boysens are the third couple central to the formation of the Berlin Red Orchestra. Harro Schulze-Boysen was secretly a communist but became a Luftwaffe officer and found a job in the Nazi Air Ministry. From this position Harro was able to pass detailed military information on to the Soviets, especially in the months before the implementation of Operation Barbarossa. Harro also played an important role in the domestic anti-Nazi propaganda campaign and was responsible for recruiting many other anti-fascists into the Berlin Red Orchestra.

Libertas Schultze-Boysen was the aristocratic wife of Harro Schulze-Boysen. Although she had briefly joined the Nazi party on a whim in her youth, she came to actively resist the Nazi regime. She worked in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s Berlin branch as a press secretary and later in the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. The Propaganda Ministry job proved to be especially advantageous because it allowed Libertas to collect evidence of Nazi atrocities both on the field of battle and in the camps. Libertas hoped to use this evidence in war crimes trials against Nazis after the war. Libertas also helped disperse anti-Nazi propaganda and facilitated bringing anti-Nazi intelligence to the Soviets.

The Harnacks, the Kuckhoffs, and the Schulze-Boysens were by no means the only important members of the Berlin Red Orchestra. Scores, perhaps in hundreds of resistance fighters were responsible for the work of the Red Orchestra. Their contributions are less well known, but they risked just as much as the Harnacks, Kuckhoffs, and Schulze-Boysens. Other key members of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack circle were John Seig, Helmut Himpel, Cato Bontjes Van Beek, Helmut Roloff, Kurt Schumacher, Hans and Hilde Coppi, the Enelsings, the Weisenbords, and the Graudenzes. Due to these members’ wide-ranging political leanings, social statuses, and occupations, they were able to serve the Red Orchestra in many different capacities. The majority of these activists were ultimately killed by the Nazis for their actions.

Considering the communist ties within the Schulze-Boysen group, the Soviet Union seemed like a natural country to share anti-Nazi intelligence with. It is important to note that just because several members of the group had communist ties, they did not necessarily support Stalin or his policies but rather saw him as the lesser of two evils. Martha Dodd, daughter of American Ambassador William Dodd, once wrote that Arvid Harnack “did not like what Stalin was doing,” and that he “spoke vehemently” against Stalin’s actions (Nelson, 119). The group first approached the Soviet embassy in Berlin with information concerning a German invasion of Russia, later to be known as Operation Barbarossa. Despite his initial reception at the Soviet Embassy, Harnack lost contact with the Soviet Union for a time following Stalin’s purges and their disruption of the intelligence community (Nelson, 160). Then in 1940 a new Soviet agent, Alexander Korotkov, sought out Arvid as an intelligence source (Nelson, 185). Hoping to gather a wider range of knowledge, the Soviets asked Arvid to bring some of his friends into the Soviet circle of intelligence (Nelson, 188). Complying with the Soviets’ wishes, Harnack brought Schulze-Boysen into the circle of intelligence. Harro Schulze-Boysen’s position within the Luftwaffe gave him access to privileged information regarding military movements and plans. Furthermore, Arvid Harnack’s position at the Department of Economics gave him access to information on Germany’s dependence on raw materials from Russia. Harnack and Schulze-Boysen’s intelligence information, however, was not met with immediate acceptance from the Embassy. Despite the accurate and extremely important information that Harnack and Schulze-Boysen was giving to the Soviets, they did not trust the informers and insisted that the members of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group needed to prove themselves as reliable sources. Gaining Korotkov’s trust was an important hurdle to clear, but Korotkov still needed to convince Soviet intelligence in Moscow that his information was accurate. In Korotkov’s superiors’ views, his intelligence “came out of nowhere.” (Nelson, 194). Soviet Intelligence headquarters “kept pressing Korotkov for documents complete with stamp and signature” (Brysac, 286). In January 1941, for example, Harro provided Korotkov with detailed plans for Operation Barbarossa from the Air Ministry but the Soviets were unprepared when the attack actually took place. A major limitation regarding Harro Schulze-Boysen’s intelligence was that Stalin’s intelligence service was unfamiliar with German air force terminology so his reports were sometimes mistranslated (Nelson, 192). Also in early January 1941, Harnack informed the Soviets that the Nazi Economics Ministry had ordered the Military-Economic Department of the statistics administration to prepare a map of Soviet industrial flights (Nelson, 191). Stalin, however, wanted to hear none of it.

One of the primary obstacles the Red Orchestra faced in having their intelligence heard was Stalin’s refusal to heed their warnings of a Nazi attack on the Soviet Union. Stalin did have reason to doubt Nazi aggression. The Nazis and the Soviets had signed a non-aggression pact, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, in 1939. Upon signing this pact German and Soviet forces divided and occupied Poland. After the division of Poland, the two powers signed the German-Soviet Commercial Agreement of 1940. This agreement arranged for the Soviet Union to send raw materials to Germany, while Germany sent machinery, weapons, and military intelligence to the Soviet Union. Then again in January 1941, the two countries signed another economic treaty, the German-Soviet Border and Commercial Agreement. It is understandable that Stalin could have assured himself that these pacts were proof that Hitler was not going to attack the Soviet Union.

Stalin had other reasons to deny a Nazi attack. Germany was dependent on natural resources from the Soviet Union, including oil from vast oil fields in the Soviet Caucuses. In 1940, three-quarters of the Soviet Union’s oil and grain exports, two-thirds of her cotton, and over ninety percent of her wood exports were to the Reich alone (Wegner, 110). In fact, the Soviet Union and Germany had been important trading partners for some years. On November 26, 1922 the two countries signed an agreement in which the German aviation firm Junkers Flugzeugwerk produced plane engines for the Soviets. In 1923 two similar agreements were signed; one concerned the production of munitions and military equipment, while the other called for the construction of a new chemical plant (Suvorov, 17). Perhaps Stalin reasoned that the Nazis would not be able to sustain themselves without these resources and used this as security against an attack.

Another disincentive for Germans to attack the Soviet Union was the challenge of conquering the massive Soviet lands and avoiding the Soviet winter. Ultimately, the sheer mass of the Soviet Union, combined with harsh winter conditions that the Germans weren’t prepared for, led to a Soviet victory. In The Chief Culprit, Viktor Suvorov echoes this assumption. He writes, “Hitler’s only chance was a lightening war, a blitzkrieg. But blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union was impossible, because it stretched more than ten thousand kilometers from west to east…In addition, a regular European army could carry out a successful offensive on Soviet territory only four out of the twelve months of the year, from May15-September 15” (Suvorov, 238).

Stalin may have thought the British were agitating to for a German-Soviet war to distract the Germans from attacking Britain (Suvorov, 233). On June 13, 1941, Molotov reminded the German ambassador in a call reported by TASS of the assurance that neither the Soviet Union nor Germany would attack the other. At this meeting Molotov also cited that, “enemies of Germany and the USSR interested in unleashing and broadening war were trying to make them quarrel and were spreading provocations and rumors of imminent war. In the announcement, these “enemy forces are listed by name; the British ambassador in Moscow, Mr. Kripps, London, and the English press” (Suvorov, 220). Whether these British warnings were simply mishandled or part of a German counter-intelligence plan is unknown, but they were effective in making the Soviets wary of British motives. Further evidence of Stalin’s fear of Britain’s fate in the war is echoed in a statement Stalin made to his entourage that, ‘as long as Germany does not settle her account with Britain Germany would not fight on two fronts and would keep to the letter the obligations undertaken in the non-Aggression Pact.” (Wegner, 347). Suvorov argues that Stalin had “driven [Hitler] into a strategic impasse by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact,” because “inevitably Germany had two fronts.” Suvorov goes on to suggest that, “Stalin simply could not understand that having found himself in a strategic impasse, Hitler would take such a suicidal step” (Suvorov, 247). Whatever his precise reasons were for ignoring multiple accurate and detailed reports of an imminent German attack, Stalin was the Red Orchestra’s biggest obstacle to being listened to having their intelligence put to good use in the Soviet Union prior to Operation Barbarossa.

In the attempt to maintain contact with the Berlin Red Orchestra in the case of a German attack (Nelson, 202), the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group was given radio transmitters to relay more information to Moscow (Nelson, 196). Following the launch of operation Barbarossa Soviet intelligence, and more importantly Stalin, were convinced of the utility of the Red Orchestra in Berlin. Once this circle of resisters had proven themselves, the Soviets became their most eager recipients of intelligence. In fact, Brysac states that, “During the year 1941, some five hundred radiograms from secret transmitters were picked up in the West by the Funkabwehr and the Ordungspolizei (Brysac, 293). Surely not all these transmission were sent from the Berlin Red Orchestra, but their information was undoubtedly broadcast among the transmissions the Germans picked up. At this point, the Berlin Red Orchestra’s main challenge was the constant failure of the Soviets’ radios and sporadic contact with intelligence agents.

The Berlin Red Orchestra met very limited success contacting the British government. Their closest connection to the British government was Adam von Trott, a German diplomat. Unfortunately Trott had enemies within Britain who considered “the idea of a diplomat trying to overthrow his own government to be ‘traitorous’”(Nelson, 161). Ultimately the combination of Britain relying on alternate sources and British distrust of Trott made the British government an unwilling recipient of information from the Berlin Red Orchestra.

The Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group had somewhat greater success reaching out to the Americans. William Dodd was appointed ambassador of Berlin in the early days of the Nazi regime. Through Dodd, or more specifically his daughter Martha, the group that was to become the Berlin Red Orchestra first tried to relay intelligence. The group became acquainted with the Dodds through Mildred Harnack. Mildred and Martha Dodd shared a love of literature and were soon friends. Dodd was very concerned with the direction that Germany was headed in, but most at the embassy and in the States did not share his concern. Although the Americans were not especially interested in the Harnacks’ intelligence information, the Harnacks used the Dodds’ social gatherings to network with others who opposed fascism and Hitler’s regime, and to expand their network. When Martha Dodd entrusted Mildred Harnack with compiling a guest list for a literary tea party, for example, Mildred took the opportunity to invite people she thought were sympathetic to anti-fascist resistance. Upon reflecting on the event, Mildred remarked that “the reception provided a welcome opportunity for anti-Nazis to gather in a group”(Nelson, 92). It was through casual social gatherings like these that the Berlin Red Orchestra grew.

In 1937 the US sent Donald Heath to Berlin in the capacity of first secretary in the Berlin Embassy. He was also a military attaché, charged with collecting information on the German economy, concentration camps, and the status of Jews under the Third Reich (Nelson, 120). Arvid Harnack, with his position at the Economics Ministry, was a natural contact for Heath. While Heath valued the economic information that Harnack gladly have him, convincing US officials of Harnack’s reliability was a struggle (Nelson, 120). Washington was skeptical of sources with Nazi party membership and their true allegiances. Heath sent Arvid’s analysis to Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles, but Welles had only mild success in dispersing this information. According to Anne Nelson, author of Red Orchestra, Welles was “far from an ideal advocate within the bureaucracy” because he had many enemies (Nelson, 160). Harnack’s economic intelligence to the US through Heath was helpful to an extent, but Heath was reassigned to Santiago, Chile, in 1941. Contact with the US was cut off after the closure of the embassy in 1941. The Berlin Red Orchestra was successful to a certain extent in dispersing intelligence to the US government, but distrust of Nazi party members combined with an isolationist mindset on the part of the US before the attack on Pearl Harbor meant that the Schulze-Boysen intelligence was not applied in a significant way by the US government.

Intelligence and espionage work is extremely dangerous, especially in a totalitarian regime like the Third Reich. Offenses like printing leaflets, owning a clandestine radio, or even an act as simple as plastering a subversive sticker on a wall carried the death penalty. Despite these risks, however, it was ultimately Soviet blunders that led to the downfall of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group.

The Soviets’ first error was providing the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group with broken radio transmitters (Nelson, 221). Every time the group took a radio to the Soviet Embassy for repairs they ran the risk of being discovered with a transmitter. Even keeping the radio at home was dangerous since surprise searches could occur at any moment. The radios constantly broke down, making contact with the Soviet Union extremely sporadic. The Soviets had the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group run a great risk with very little real positive impact.

As previously mentioned, there were three independent groups within what the Gestapo called the Red Orchestra. One group was headquartered in Brussels under the leadership of Leopold Trepper, a Jewish Pole turned Soviet agent. The Soviets sent two more agents to assist him in western Europe. One of these agents was Anatoli Gourevitch. Despite his training as a Soviet spy, Gourevitch proved to be an extremely ineffective agent. In response to the lull of messages coming out of Berlin from the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group, the Soviets sent Gourevtich to Berlin to re-establish contact with the group. Through a coded radio transmission the Soviets included the names and addresses of the Kuckoffs and the Schulze-Boysens (Nelson, 225). After meeting with the Kuckhoffs and the Schulze-Boysens and learning that their radios were broken Gourevitch returned to Brussels and eagerly transmitted all the information he had gathered from the Berlin Red Orchestra for seven nights in a row, for five hours every night (Brysac, 312). Even worse, he transmitted his information at the same time every night, from midnight to 5am (Brysac, 312). By doing this Gourevitch and the Soviets broke two essential rules of radio espionage. First, by broadcasting for extended periods of time for several nights in a row Gourevitch made his radio signal traceable. Secondly, by broadcasting at the same time every night the Germans knew when to listen for these signals. At 2:30am on December 13, 1941 the Gestapo raided the Brussels villa from which Leopold Trepper and Gourevitch were working. Neither man was there at the time, but the Nazis were able to capture some charred code sheets that helped them crack the Soviet encryption (Brysac, 312). The Soviets’ most grave error was to broadcast the names and addresses of informants over the airwaves. When the broadcasts were first intercepted Nazi intelligence did not understand the code of the message, but after studying it they cracked the code and were able to target the Kuckoffs, the Harnacks, the Schulze-Boysens, and others. After cracking the code, the Gestapo began secretly following members of the Berlin Red Orchestra to discover the extent of the group.

After trailing the group for some time, the Gestapo sprang into action on August 31, 1942 when they arrested Harro Schulze-Boysen at his office in the Luftwaffe Ministry (Brysac, 9). Within the next few weeks the main players in the Berlin Red Orchestra were all under arrest. In the book Resisting Hitler Brysac writes, “by March 1943, there had been 139 arrests in connection with the ‘Red Orchestra affair’” (Brysac, 9). This number pays testimony to how far-reaching the Schulze-Boysen group had become by the time of their capture. A series of quick trials found all arrested members of the group guilty. Most of the Berlin Red Orchestra was executed by the Nazis at Plötzensee Prison during the end of 1942 and the beginning of 1943. Greta Kuckhoff was one of the few survivors of the Schulze-Boysen group. Although she was imprisoned until the end of the war, Greta’s salvation came from her limited involvement in Red Orchestra activities.

After being liberated from prison following the defeat of the Nazis, Greta Kuckhoff returned to her son Ule and fought to honor the memory of her friends in the Berlin Red Orchestra. The fact that she was one of the few survivors of the Schulze-Boysen group meant that Greta had to work hard just to make Germans aware of the work she and her friends had done. After the war Greta moved back to her old apartment, which happened to be in US-occupied West Berlin. Here Greta ran into trouble publicizing the work of the Berlin Red Orchestra because it was considered a communist resistance group by the US. Although it is true that many members of the group were communists or socialists and that the Soviets received the majority of the group’s intelligence information, the focus of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group was to defeat fascism for Germany’s sake. They did not agree with many Soviet policies and should not be viewed as a Soviet resistance group, but rather a German resistance group. Regardless of how the Berlin Red Orchestra classified themselves, the US occupying forces did not want to promote the efforts of a ‘communist’ resistance group. Frustrated by what Greta considered a return to the pre-war status quo in West Berlin, she moved to Soviet-occupied East Berlin. Here Greta was certain she would have greater success in glorifying the deeds of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group. She was successful to a certain extent. Her bravery was rewarded with a good apartment, employment opportunities, awards, and invitations to ceremonies. Even the Soviets, however, did not always find it advantageous to celebrate the Berlin Red Orchestra’s work. When Greta wrote a book about the Berlin Red Orchestra, for example, her writing had to undergo extensive censoring. In particular, the Soviets objected to her references to religion and race. They felt that she was turning her account into race-based story when they wanted to market a tale of the working classes overthrowing the Nazi elite. Despite restrictions from both the US and the USSR, Greta Kuckhoff continued to tell the story of the work carried out by the Berlin Red Orchestra. Recently there has been a rediscovery of their heroic work, beginning with Brysac (2000) Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra, and more recently Nelson (2008) The Red Orchestra: the story of the Berlin underground and the circle of friends who resisted Hitler. This renewed interest in the Berlin Red Orchestra may be the result of the end of the Cold War.

The members of the Berlin Red Orchestra put their lives at risk to resist the Nazis because they felt a moral obligation to do so. Almost all the members of this group, especially the founding members of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group, could have lived out the war in relative comfort due to their positions within the Nazi regime. Instead, they reached out to several Allied countries in an effort to spread intelligence that would defeat Hitler. Despite difficulties in dispersing their information, the group continued to cultivate contacts and broadcast intelligence until their capture. The extremely small number of surviving group members is part of the reason why the legacy of the Berlin Red Orchestra is so obscure. Political motives of both East and West Berlin authorities were also an important factor in ignoring the important contributions of the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group. Ultimately, however, the work of the Berlin Red Orchestra did help bring about the downfall of the Third Reich. Harro Schulze-Boysen once told his friends, “If the Russians come to Germany (and they will come) and if we are to play some role in Germany, we must be able to show that there was a meaningful resistance group in Germany. Otherwise the Russians will be able to do what they want with us.” (Nelson, 250). The actions of the Berlin Red Orchestra show us that even under the most difficult circumstances it is possible to stand up for what is right and what one believes in.

|