|

Essay (back

to top)

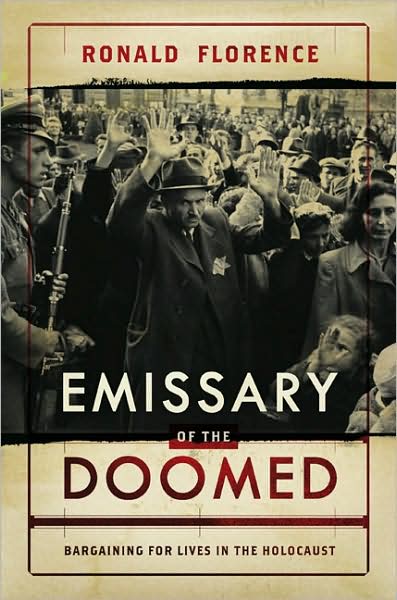

In December 1941, a refugee ship carrying seven hundred and sixty nine passengers was refused entry into Turkey and British occupied Palestine. Instead, after two months of waiting with no fuel, food, or heat the Struma was tugged three miles out to sea and blown up, killing all but one passenger. The reason for the tragedy was because of the status of Jews in the Allied community. In this case, the British refused to increase immigration to Palestine leaving refugees on their own. Similarly, the Hungarian resistance movement had to deal with the same frustrations and set-backs due to the international perception of Jews. In Emissary of the Doomed, the author, Ronald Florence, describes the failure of Joel Brand to effectively negotiate a rescue deal with Nazi officers, due to an ineffective Jewish Agency and an Allied vision for the war effort. I think that this reveals an underlying Allied prejudice against rescuing Jews.

Jewish Agency

Florence examines the misperceptions between the Jewish Agency and the realities of Jewish deportations as a hindrance for an organized rescue. For instance, the Jewish Agency was unable to comprehend the realities of the mass-murders committed by the Nazis against the Jews. The author recounts how Slovakian Jewish leaders had been keeping strict property records of Jewish valuables so that they could return them when their owners returned (Florence, 15). To many Jewish people, the killings were only rumors. With all the propaganda, it was difficult to disseminate the truth. However, in April 1944, the Auschwitz Protocols provided a concrete account of Nazi killings. The report described the Nazi gas chambers, crematories and deplorable conditions from two escapees of Auschwitz, named Rosenberg and Wetzler (Florence, 15). Florence argues that Jewish leaders in Palestine failed to act on the report, leaving Joel Brand’s mission in the dark. Joel Brand characterized the desperate situation stating, “no one who hadn’t lived under German occupation could understand the totality of the experience” (Florence 106). Armed combat was futile against German brutality. Jewish leaders did not fully understand Nazi occupation and deportation. Thus, they could not come up with a useful solution. Moreover, Brand was given a deadline of two weeks to respond to Eichmann with a counter-offer. The Jewish organizations’ inability to collectively reach a solution and act quickly threatened to derail the negotiations.

Part of the reason for the internal dissention was the conflict between Zionist goals and British immigration restrictions. For instance, the Jewish Agency, established in 1933, was supposed to have a significant non-Zionist representation to voice the views of the refugees opposed to an independent Israel state (Florence 137). However, during the war, Jewish leaders had to balance a tight rope between British policy and their own goals of Jewish immigration to Palestine. The Jewish Agency had to screen qualities for the ideal Jewish in the new state of Israel. The organization focused its attention as a political state in waiting, leaving no room for Joel Brand’s rescue. Moreover, much of the time, refugees who had escaped war-torn Europe had found themselves detained in British camps outside of Aleppo while the British reviewed their immigration status. The Allied policy was a compromise between a minority Jewish population and a larger Arab population in Palestine. British leaders did not want to exacerbate conflict between the two groups while there was a war going on. However, I also believe that prejudice and the marginalization of Jewish refugees help to fuel British policy of reduced immigration.

Finally, Florence argues that the Jewish Agency faced public image problems on several different levels that impeded organization and action for an effective relief effort. First, the myth of a semi-secret network of world Jewish domination compromised the reputation of the Jewish Agency in Axis and Allied governments. The antisemetic Protocols of the Elders of Zion or Walter Scott’s popular novel Ivanhoe, created a stigma of Jewish domination (Florence, 137). Thus, people tended to disfavor support for the Jewish Agency during the war. The Jewish Agency’s goal for immigration to Palestine always remained the utmost political priority, which created image problems that help to belittle rescue efforts. For instance, eager to maintain connections to Europe, the Zionist organization cabled condolences to Hitler in the 1930s when President Hindenburg had died (Florence, 138). Publically, the Jewish Agency was not consistent in their goals. The organization’s political goals hindered their comprehension of the Holocaust and the plight of European Jewish refugees. The identity crisis was only dealt with after the war with the testimony of Joel Brand against Reszo Kasztner. Kasztner was recognized in the trail’s conclusion as having dealt with the Nazis against his people’s suffering. The emphasis on immigration trumped concerns for European Jews. In essence, the religious stigma of the Jewish Agency in the Allied community and the organization’s focused priority blocked any effective offer for Jewish rescue.

Although Joel Brand’s hopes for collecting ten thousand trucks may seem far-fetched, a counter-proposal would have at least given time for the Hungarian Jews. The Auschwitz Protocols had designated a large ramp being built to accommodate the one million expected Hungarian Jews to enter the camp. Even delaying just a day would give chance to some twelve thousand Jews transported to the camp every day. However, not only did delays from the Allies further doom the Jews to Auschwitz but Joel Brand was never able to return to Budapest.

International Struggles

Florence argues that the Allied wartime priority prevented Jewish rescue, to which I think, reflected an Allied prejudice. For instance, when Joel Brand came to British controlled Cairo at Aleppo in hopes of contacting an Allied leader; he was detained, questioned, and held under guard. The British had labeled Joel Brand as a Nazi agent and the proposed deal as a Nazi trick. Thus, the intentions of Joel Brand were undermined by the fact that he was a Hungarian Jew. The British doubted the plausibility of Brand’s sources because of his identity. Moreover, the British knew that Bandi Grosz, the Smuggler King of Hungary who accompanied Joel to Istanbul, was a double agent. Whether it was for the Allies or the Axis, Grosz was simply out to make a profit. The Allies believed Brand’s association with Grosz helped to manifest his characterization as a Nazi agent. Yet, labeling Brand as a Nazi agent was based on racial underpinnings. There was no reason for the British to consider Brand a threat other than his Hungarian Jewish identity. The detainment of Joel Brand by the British further undercut any hope of saving Jewish lives in Hungary.

Similarly, the United States and their international organizations, like the War Refugee Board, remained ineffective and unwilling to use resources/materials for what they considered secondary to victory against the Nazis. For instance, in 1943 a group of Treasury officials “obtained proofs of the State Department’s deliberate avoidance of the refugee problem,” prompting the creation of the War Refugee Board (Florence, 173). Resentment in the US for the prominence of Jews like Henry Morgenthau of Wall Street or the Jewish prevalence in Hollywood characterized some of the ignorance that was prevalent in governmental areas, like the State Department. Moreover, another US branch, the Office of Strategic Services, predecessor of the CIA, disregarded the Jewish question. For instance, OSS agents had established a small navy in Turkey but had refused to use the boats for the rescue of Jews who had escaped Europe (Florence 131). The US government had promoted the wartime effort on a foundation of marginalizing Jewish rescue. The political ramification of the refugee question was merely an after-thought, something that could be dealt with at the end of the war.

The War Refugee Board established in 1944 by Franklin Roosevelt provided no more effective response to the Jewish question than had been available before its existence. For instance, the funds allotted to the organization only covered staff and overhead expenses with little appropriations deemed for actual aid. Even when Saly Mayer was in negotiations with Nazi officers like Becher, and the new Vaada leader Reszo Kasztner, appropriations by the WRB “held firm to their policy of no ransom payments to the Nazis” (Florence, 257). The WRB was counting on the fact that with Germans defeat not long off, they simply needed more time by delaying the Nazis in negotiations. The Allies refusal to offer a better solution reflected a prejudice for Jewish relief. Even Jewish leaders, like Moshe Shertok could offer nothing better than words, stating, “the goal, Shertok thought, was to gain time, not by doing nothing but by taking action” (Florence 149). Sadly, the Allied effort did not take needed action to rescue the Jews, reflecting a focused wartime priority based on Jewish resentment.

The Allied strategy remained indifferent to diverting any war material into rescue efforts for the Jews heading to the Auschwitz camp. For instance, Slovakian Jewish leaders had urgently sent messages to the British to bomb precise sites over Kosice as one of the major junctions for the deportations coming through the city (Florence, 192). Additional messages of new bombing requests arrived to the U.S. Army Air Corps to bomb the Auschwitz gas chambers and railroads leading to the camp. By bombing the facilities the Germans would be forced to rebuild and this would allow valuable time for the Jewish prisoners. However, after consideration, the Allied authorities jointly denied the requests stating the facility was “beyond the range of the available bombers…the distance was too great…and they lacked precise targeting information” (Florence 193). Yet, the author looks at the airfields in Italy and the use of available Soviet airbases in Poltava, due to Operation Frantic, specifically for refueling long-ranged missions. The Allies could have easily set up operations to bomb the specified targets. The response reflected an Allied reluctance to rescue Jews. Moreover, Florence defends the precision of British Mosquito light bombers that helped to free prisoners of war in Amiens (Florence 194). The bombed facilities would have given the prisoners of the transit camps much needed time to survive the gas chambers of Auschwitz. If the WRB and reports from the Jewish Agency claimed a policy of more time, why would the Allies refuse to potentially give that time? As reference, it took the Germans eight months to build the gas chambers in Auschwitz. To reiterate, Allied front prioritized victory above all, no matter how humane the missions might be, and would not allow any war material to help the Jewish relief. The Allies’ priority reflected animosity for Jewish rescue.

In conclusion, Florence argues that the Jewish Agency and the Allies inherent priorities and conceptions of Jews acted against an effective relief effort. I think that this reflected an Allied prejudice against Jewish rescue. Only later, did Joel Brand’s testimonial trials of Reszo Kasztner, help to bring long ignored atrocities of the Holocaust into the political sphere of the new country of Israel. It was something that had been long buried due to the ill-will that it might bring to the new political parties.

|