Essay (back

to top)

Book Summary

Diane Ackerman’s book, The Zookeeper’s Wife is a collection of diaries written by a Polish woman in Warsaw during the Nazi occupation between 1939 and 1944. The aftermath of the initial attack left the Warsaw Zoo in shambles, and its keepers Jan and Antonina Zabinski were left with its upkeep while German soldiers pillaged the remaining animals and grounds as game and their own personal park. Soon thereafter, with no other means of livelihood available, Jan began participating in the underground resistance movement and the Zabinskis began harboring Jews and political exiles in cages and underground labyrinths originally created for the zoo’s animals.

Antonina’s diaries begin a few days before the Nazis invaded Poland and continue up until a short time after 1945, recalling the aftermath of the war and the beginning of the restoration process. Ackerman follows a chronological progression, framed largely by Antonina’s recollections, but also includes key moments during the occupation that in one way or another shaped the war for the Zabinskis and their guests.

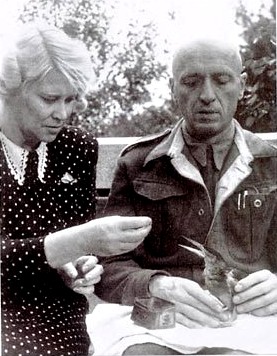

Antonina, in her memoirs, and Ackerman in the book, relate many of the Zabinskis' experiences to situations regarding animals and their deep connection to the larger animal world. As a caretaker from the beginning, Antonina naturally “reigned as a mammal mother and protectress of many others.” Her disposition made her the perfect caregiver in a household of strays, both human and not.

Ackerman uses these experiences and personality quirks to create a deeper understanding of the relationship the Zabinskis had to their guests and of their innate need to do right by others. Jan’s background as an animal psychologist gave him unique insight into the personalities and characteristics shared by both humans and animals, while Antonina’s wild and deep connection to the animal world enabled her to more easily access the inconsistencies in German disposition and use them to her advantage.

The Zabinskis’ well-known status in Warsaw as friends to humans and animals also facilitated their connections to prominent Germans and pro-Nazi Poles, giving them additional sources of subsistence and coal during the harsh Polish winters, allowing for the prolonged stay of multiple guests. While for the most part the Zabinskis’ villa was a gateway to the larger resistance movement for traveling refugees, there were occasions in which their guests would stay for prolonged periods of time, further strengthening the Zabinskis’ ties to the Jewish community and the underground movement. However, as gateway, they were able to offer shelter to over three hundred individuals between the years of 1939 and 1944, “creating a halfway house, ‘a stopping place for those who escaped the Ghetto, until their destinies were decided and they moved to new [more concealed] hideouts’” (Ackerman, 114).

Ackerman uses Antonina’s diaries to frame a larger story about the Polish resistance movement, but focuses mainly on the Zabinskis’ close circle of friends. She compiles information concerning not only historical facts about resistance groups and individual Samaritans, but also some of the leading spiritual and theological perspectives to give readers a more in depth and wide-ranging perspective on Polish resistance during World War 2.

Unwavering Bravery: Polish Heroes in Warsaw During Nazi Occupation

Diane Ackerman uses Antonina Zabinski’s memoirs as a frame of reference to describe the greater underground movement in Warsaw and its surrounding areas during Nazi occupation. Antonina’s diaries, her hopes and her fears, give life and substance to what was really happening to people within the underground movement and the burdens fugitives carried with them because of the danger posed to those protecting them. The diaries help to illustrate the types of people that participated in the resistance, and the lengths to which they would go to protect those around them. These people were usually average Polish citizens who were, for some reason or another, against the Nazi regime and felt it their duty to assist Jews as a type of resistance.From this starting point, Ackerman then uses various sources to give both spiritual and factual histories about resistance groups and individuals who stuck out particularly in her opinion in Poland during the Holocaust.

For example, Ackerman mentions a prominent Jewish orphanage director in Warsaw who, when offered an escape, instead moved to the ghetto with his orphans to take care of them and provide security for their well-being during a time of frightening uncertainty. Then, in 1942 Henryk Goldszmit displayed unwavering bravery once again, in accompanying his charges to the gas chambers of Treblinka to await a certain death (185). An eyewitness account recalls the scene:

A miracle occurred, two hundred pure souls, condemned to death, did not weep. Not one of them ran away. None tried to hide. Like stricken swallows they clung to their teacher and mentor, their father and brother, [Henryk Goldszmit] (186).

Although such acts of bravery were not uncommon, Ackerman describes in detail this formerly prominent writer’s need to take care of these children both physically and spiritually.

Another uncommonly brave character mentioned is Feliks Cywinski, a World War 1 veteran and old friend of Jan Zabinski. Cywinski had two apartments in which he hid and “fed as many as seventeen people, providing separate pots and dishes for those who kept kosher” (218). After caring for so many people so generously, Cywinski soon ran out of money. And, “when his money ran out, Feliks went into debt, sold his own home, and used the profits to rent and furnish four more apartments for hiding Jews” (219). Others like Feliks Cywinski who hid Jews would count on the assistance of carpenters and architects involved with the underground to assemble false walls and bunkers where several people could hide while German soldiers searched houses and apartments to no avail (119).

Dr. Marda Walter and her husband offered yet another exceedingly brave, but this time unusual, gesture of goodwill. Their contribution to the underground resistance movement was the Institut de Beaute where they taught Jewish women “how to appear Aryan and not attract notice” (220). These lessons included learning the catechism and how to cook traditional Polish meals, including pork. This “kind of charm school [was in] the charm of nondetection” (221), which also included changes in speech and sometimes even plastic surgery. These services were, of course, only used in the most dire circumstances and included nasal reconstruction and plastic surgery to restore foreskins on Jewish men to hide those traits considered inherently Jewish. While Mrs. Walter’s services did not include housing Jews, her actions put her and her family at risk, and showed a great amount of generosity considering that most of the procedures were done at very low costs to the patients (222).

Ackerman illustrates the Zabinskis connection to the underground network and people such as those mentioned above to make real the need for wholly selfless people. She explains the complexities of getting proper documentation for those trying to escape the horrors of the Nazis. “Each escapee [from the ghetto] required at least half a dozen documents and changed houses 7.5 times on average…between 1942 and 1943 the Underground forged fifty thousand documents” (140). Secret meetings in cafes, the changing of names or code names such as the animal names given to the guests at the Zabinski villa, secret underground conspirators working directly with the Nazis undetected were all essential to the proper functioning of underground missions. There was an entire stream of information that had to be protected or else the entire underground movement would have been exposed. As many people recall there was an unforgivingly systematic documentation system set up by the Nazis who

aimed step by step, by means of interlocking decrees, to create a reporting and documentation system that would render any kind of [resistance] machinations impossible and that would locate any single inhabitant of the city with appropriate precision (243).

Thus, the necessity for organizations such as the Zegota [a “cryptonym for the Council to Aid the Jews” (187)], was closely connected to the existence of such “safe houses” as those run by the Zabinskis.

Throughout the book, Ackerman portrays extremely pious and exceedingly brave men and women. Those who merely acted in accordance with Nazi laws were not included, and were discreetly dismissed as just as bad as the Nazis for their non-participation in the resistance. Like Jan and Antonina, who risked their own lives and the life of their son, Ackerman’s characters only display the most radical and unwavering bravery and resistance.

This approach sheds a much different light on the actions of non-Jewish Poles during the Second World War, as they are usually depicted as antisemitic. Ackerman does not disregard the presence of antisemitism, she knew “it still percolated in twentieth-century Warsaw, a city of 1.3 million people, a third of whom were Jewish” (23). This dichotomy between Ackerman’s Poles and one’s normal association is quite unusual. It also takes away some of the attention normally paid to Jews, and gives the reader a view into the life of a non-Jewish hero (or heroes) who had no ties to the Jewish community in a familial way, but still felt it their duty to help them. For Antonina

There was no alternative, really [to being in the underground]. One needed it to face the stultifying fear and sadness aroused by such daily horrors as people beaten and arrested on the streets, deportations to Germany, torture in Gestapo squads or Pawiak prison, mass executions. (99)

Ackerman highlights the hostile situation Poles were in, considering their lesser place within the Nazi hierarchy. While harboring a Jew was punishable by death in most countries, in Poland, one was more likely to be snitched out or otherwise given away, sometimes simply for an extra ration of sugar or bread:

Unlike other occupied countries, where hiding Jews could land you in prison, in Poland harboring a Jew was punishable by death to the rescuer and also to the rescuer’s family and neighbors, in a death frenzy deemed ‘collective responsibility.’ (116)

While this was both due to the fact that there was a much larger Jewish population in Poland, and the fact that Germans also considered Poles a lesser people like the Jews, one must consider this when reading about the determination of these members of the underground to help the Jews. Their situation was much more dangerous because of the hostile political environment, and most Poles were unwilling to risk their lives for Jews, so these participants mentioned in Antonina’s diary and Ackerman’s side-notes were the most daring of rescuers.

Ackerman’s story introduces many unusual and uncommon “truths” through the eyes of the zookeeper’s wife. Antonina makes no effort to conceal her knowledge of the concentration camps: “by now everyone understood that ‘resettlement” meant death” for the Jews (202). Unlike the usual bystanders however, Antonina also does not seem to comprehend that one could not help others in such a time. She never mentions her fear in relation to not being able to help, only her concern for those she loves and her desire to do more for the poor guests whose lives have been utterly destroyed.

Antonina explains the difficulty associated with helping so many people and yet not being able to help them all. “The ‘heavy ballast of being responsible for the lives of others’ slid around her body and stole through her mind as an obsession” (275). As a coping mechanism, as was for many witnesses to the Holocaust, denial protected bystanders from accepting the reality of Nazi cruelty. Antonina mentions specifically that it was not her alone, but her Jewish guests as well, who could not stand to think of the atrocities being committed:

As long as we didn’t witness such events themselves, feel it with our own skin…we could dismiss them as otherworldly and unheard-of, only cruel gossip, or maybe a sick joke. (103)

Regardless of what they knew or didn’t know, the Zabinskis risked everything they had to save as many people as they could. Ackerman illustrates this in The Zookeeper’s Wife and makes clear the importance of the underground and the interconnectedness of the community involved in saving as many people as possible.

|