Essay (back

to top)

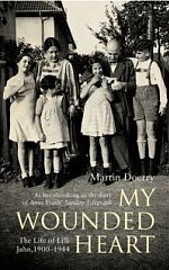

My Wounded Heart is a painful story of one exceptional woman and her struggle for normality during the Holocaust. Through letters preserved by her surviving relatives and friends, readers are able to better understand the daily challenges of an educated Jewish woman and her “mixed” family during this horrific time period. History books, documentaries and other sources on the Holocaust tend to place emphasis on the overall Jewish experience rather than discussing family life in an in-depth manner. Although Martin Doerry focuses mostly on the life of his grandmother, My Wounded Heart provides a gripping example of daily life for many Jewish families. Lilli’s death not only affected her but her five children. At the time of her arrest she had five children: Gerhard was sixteen, Ilse fourteen, Johanna thirteen, Eva ten, and Dorothea only two. By reading the story of Lilli Jahn and comparing it with Kaplan’s Between Dignity and Despair, one can deduce that Lilli's story is not an anomaly and therefore illustrates many generalizations about the Holocaust experience for intermarried Jewish women and their families.

Lilli’s Youth

Lilli Jahn, born in Halle in 1900, had a normal and optimistic youth, but was well aware of increasing political tensions and the consequences of her Jewish heritage. Lilli came from a middle class German Jewish household and as a child enjoyed a relatively privileged life secluded from pre- and post-World War One political developments. After the proclamation of the Republic and rising inflation, Lilli’s father joined the political arena due to business difficulties and general insecurities about his family’s future. Josef Schluchterer feared that a rising Jewish immigrant presence in the area would lead to increases in antisemitic behavior. The “Jews were blamed for everything, for losing the war, for the humiliation of Versailles, for inflation…”(Doerry 6). Lilli’s father saw this new, mostly uneducated and poor immigrant population as threatening to the comfortable middle class existence he had established. Around this time Lilli had entered medical school where she began to suffer from anti-Semitism, although mildly at first. In her letters she complained to Ernst, her college boyfriend and peer, that other students did not think she was as academically capable since she was Jewish. The rise of the right wing National Socialists began to concern her and even caused her to vote leftist in the Reichstag elections of 1924 (16). Even within her courtship to Ernst one can easily see Lilli was concerned about being Jewish although she had no intentions of leaving her community. In several letters she convinces Ernst that they will be happily married despite professional problems she feels he will have through association with her (22). Lilli enters adulthood successfully but political pressures and rising antisemitism did cause her concerns that Aryan children did not have to face.

Marriage Complications

Marriage can be a difficult prospect for anyone, but Lilli’s Jewish background further complicated this time. Lilli spent several years convincing Ernst that marriage to a Jewess would not ruin his career. He feared he would not be hired at a reputable medical clinic and even dated other women in an attempt to find a non-Jewish partner. One could argue it was actually Ernst’s weak character and unfaithful manner that slowed the marriage process, but this is not clearly expressed within their correspondence. He mentions to Lilli that he is courting other woman but it is unclear if this was because Lilli was Jewish or he simply desired other women. To assuage Ernst’s concerns Lilli began attending lectures by other religious leaders and adorned her room with images of the Virgin Mary. Lilli was attempting to blur the strict religious dividing lines in her relationship (37). Ernst was also concerned about Lilli’s career ambitions since he expected her to abandon her medical career (24). Lilli largely ignored his defensive behavior and hoped she could convince him otherwise after they were married. Lastly, Lilli had to alleviate her parents’ concerns about the nuptials because they too felt a mixed marriage would be a difficult accomplishment (31). “Mixed couples had to scrutinize their relationships with relatives on both sides of the racial divide, to define their identities to themselves and society, and to face severe familial, state, and societal pressure to separate.” (Kaplan 75) Despite enormous amounts of pressure, Lilli and Ernst were married in 1926.

Nazi Pressures Strain Marriage

Once married, negative external strains continued to work against the young couple. “Nazi intimidation caused grave tensions and anxieties in these (mixed) marriages.” (89) Already in 1933 Ernst and Lilli began to be ostracized from their small community in Immenhausen, Germany. Family friends, collogues and even the local clergyman cut ties with the family due to pressure from the Nazi party (Doerry 61). Lilli had adapted a completely Christian lifestyle and her children were even baptized in the Protestant faith; however, the Jewish stigma still plagued her family and eventually led to the disintegration of her marriage. In 1938 Jews were forbidden to attend public functions. For Lilli and Ernst this was especially difficult seeing as this was their only social outlet since most of their friends had abandoned them. Lilli insisted Rita, Ernst’s assistant, accompany him to the theatre because she did not want her husband to suffer because of her Jewish background. Within a short period Ernst and Rita were having an affair and Rita was pregnant. The local District Director took great interest in this affair. Governmental reports state a carefully thought out plan to encourage divorce so Lilli could be removed from the district. (96). After the war Gerhard, Lilli’s eldest son, took charge of the mayor’s records and found these documents. He even threatened to bring Rita to court for her involvement in the scam to deport his mother, but his sisters asked him not to exacerbate the situation. It was not uncommon for people to use the Gestapo to their advantage at the expense of their Jewish peers. (Kaplan 79). By 1942 Rita and Ernst had their first child, delivered with the help of Lilli, and the marriage was officially over. This was a huge blow to Lilli who later confessed to a friend that she did not blame Ernst. She felt that the stresses associated with marrying a Jewess were simply too much for him to handle (Doerry 103). Again, one could argue that the fate of their marriage was not caused by political pressures, or different religious backgrounds, but rather because of Ernst’s pathetic character. There are several examples of Aryan men and women who suffered terrible consequences in an effort to protect their significant other. For them divorce was not a possibility. Unfortunately, there are also several other incidences where individuals did leave, or even encourage the suicide of their Jewish partners. In Ernst’s defense, it was more likely that an Aryan man would leave his Jewish wife than an Aryan woman would leave her Jewish husband. Since other men were in similar situations and behaved as Ernst did he was not alone in his actions and probably felt justified. (Kaplan 91). Antisemitic fervor played a detrimental role in the difficulties and eventual termination of Lilli and Ernst’s marriage.

No Longer Protected by Aryan Husband

The divorce from her college sweetheart was devastating emotionally for Lilli, but now without an Aryan spouse, she was in physical danger as well. “Although Jews would suffer fierce discrimination and the destruction of their economic existence, they would not be physically annihilated because of their ‘Aryan’ relatives” (84). Her marriage to Ernst had provided Lilli with protection. Despite ostracism she was relatively safe and considered well off because of her husband’s successful medical practice. At the time of her divorce she was the last Jew left in Immenhausen. All the rest had either emigrated or been arrested. After the divorce she was under heavy surveillance because the local government saw her as their last Jewish target (Doerry 112). In 1943 Lilli placed a visiting card outside her new residence that did not conform to Nazi regulations. Lilli failed to place the required “Sara” and added “Dr.” to her name. For this she was reported to the Gestapo, arrested and sent to Breitenau labor camp. This was an extreme punishment for such a minor transgression, but the local government was determined to rid the area of all Jews. From her camp letters it appears Lilli was hoping her ties to Ernst and his family would prove useful to her. The help of one friend within the Gestapo actually allowed her to receive parcels from her children while in camp (134). Life was obviously difficult in the camp but the few comforts from home helped her survive for nearly a year and lifted her spirits. Unfortunately, Ernst could not get Lilli released from the camp, which may be because he put a request in too late. Lilli’s fate was pushed to the background in his life as he created a new family. Lilli spent several months at Breitenau and only casually mentioned to her children to ask their dad for help. Not until she realized that she would be transferred to Auschwitz did desperation enter her correspondence (242). On her transfer to Auschwitz Lilli met a former lawyer who informed her that usually single persons from mixed marriages were only deported if they had no dependent children. With this information she asks Ernst to have the Gestapo check their files in hopes it will lead to her release (247). Lilli dies in Auschwitz shortly after her transfer and never sees her children again. Her tiny transgression, which may have been a small act of defiance, led to her death because without her Aryan husband she was powerless.

Children of Mixed Marriages

Lilli’s five children were considered half Jewish, therefore, despite some security their lives were full of hardships stemming from their mother’s background. As a child, her son Gerhard ran around proudly singing Nazi songs and carrying the flag. He had no knowledge of the significance of these actions, but as he grew up began to be excluded (59). The Jahn children all stood out at school because they were not permitted to join the Hitler youth; therefore, they were the only students not in uniform (67). The children faced harsh criticism from schoolmates and teachers alike. Jewish children were often separated at school, barred from events and forced to listen to lectures on the racial superiority of the Aryan race (Kaplan 95). Jewish mothers tended to be more informed about their children’s school lives. Lilli was no exception and often wrote to her friend about the discrimination her daughters faced in school (Doerry 74). Being a strong minded woman she intended to help her children, but as the political situation continued to deteriorate this was simply not a reality (73). Lilli worried about the future for her children since they were “excluded from almost every profession and opportunity in life (67). Gerhard joined the armed forces after finishing school but shortly before the end of the war he was dismissed much to his dismay. He was considered “unfit to bear arms” and would have been arrested but persistent air raids prevented to Gestapo from carrying out their intention (255). Lilli’s children were actually almost arrested just after Lilli’s arrest due to their “half-Jewish” label. Ernst and Rita left the children in their mother’s apartment after her arrest and if a friend of the family, who was not Jewish, had not intervened the Gestapo would have taken the children into custody. Ernst only showed up after he had received a stern letter from this family friend (116). It appears this Aryan woman cared more about the safety of these Jewish children than their own father. Lilli’s children were also largely marginalized in their father’s new household. Lilli’s daughters consistently wrote their mother about frustrations regarding Rita (230). Rita did not show them any affection and all the children lived upstairs while their step-mother and step-sister lived downstairs with their father. The children largely disliked Rita because she had replaced their mother, but one can deduce tensions also existed because the children ruined Rita’s “perfect Aryan household.” She attempted to separate them as much as possible from her family. Obviously, the most difficult hardship the children faced was the loss of their mother. Isle, the eldest daughter, was fifteen at the time of her mother’s arrest in 1943 and became the surrogate mother to her sisters. The youngest daughters have limited recollections of their mother since they were quite small when she was arrested. Isle was largely responsible for managing the entire household, completing her studies and attempting to send her mother supportive packages. The on-going war made all of this very difficult since the family was constantly in fear of air raids. The challenges of the Holocaust largely robbed Lilli’s children of their childhoods since their harsh environment provided no comfort and only hardship.

Conclusion

The story of Lilli Jahn and her family is unimaginably tragic, but it is not unlike the experience of other mixed Jewish Aryan families in Hitler’s Germany. Families throughout the war experienced exclusion, separation and loss. Each story reminds its audience of the horrific ordeal European Jews faced at the hands of the Nazi party. My Wounded Heart and Between Dignity and Despair help to create a complete look at the Jewish story by examining the family element. This personal aspect creates a much more memorable impression on readers.

|