Essay (back

to top)

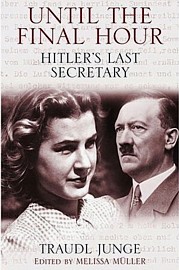

In November 1942, Traudl Junge filled a secretarial position at Adolf Hitler’s office, and this twenty-two year old youth from Munich served the Führer to his very last days in his bunker in Berlin. Six decades later, Junge embarked on an overdue mission—to publicize her memoir in a book titled Until The Final Hour: Hitler’s Last Secretary. We can draw the following conclusions from Junge’s personal accounts: first, Junge served the regime out of enthusiasm, she was attracted to Hitler’s paternal character, and because it provided her a ticket to Berlin; second, the improving economy and standard of living helped Hitler gain support from Germans like Junge; third, although Junge feels guilty for collaborating with a genocidal murderer, she was neither an antisemite nor was she aware (or possibly chose not to be aware) of the atrocities committed against the Jews. By consulting certain cases derived from Alison Owings’ Frauen: German Women Recall the Third Reich, we will compare and/or contrast Junge’s perspectives of Hitler and of the Third Reich with the perspectives of other German women who supported and collaborated with the Nazi regime.

“When I started working there I thought I was the source of information,” claims Traudl Junge, describing her secretarial job at the Führer’s office, “[when] in fact I was in a blind spot” (“Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary”). From November 1942 to the first of May in 1945, Junge served the Führer as his secretary. During the two and half years she was employed by Hitler, Junge became part of the Führer’s inner circle and established what she describes as a father-daughter relationship with him (Junge, 10). In her book Until the Final Hour, Junge writes about her experiences while working for the Führer, why and how she came “under the Führer’s spell,” and provides a unique perspective on the character of Adolf Hitler.

Born in March 1920 to a working class family, in a city where unemployment rates rose on daily basis—the so-called ‘Capital of the Movement,’ Munich—young Traudl Humps was the first daughter of Max and Hildegard Humps. Max Humps, an ex-First World War general and a passive antisemite, was a member of the Bund Oberland and had participated in Hitler’s putsch of 8-9 November 1923 (Junge, 10). Seeing that her unemployed husband rather support the NSDAP than his own family, Hildegard left and later divorced Max when Traudl was only five years old (Junge, 11). Thus, along with her younger sister, Traudl grew up at the mercy of her ‘domestic tyrant’ grandfather (Junge, 12). Growing up in the ‘Capital of the Movement,’ “[Traudl] felt proud of Germany and the German people” and decided to “stand up for the Führer” (Junge, 15). She accepted the idea of Bolshevism as the greatest enemy, but she never refused to be friends with Jewish girls (Junge, 16-17). In 1935 she became a member of the Bund Deutscher M ädel (BdM) and had one goal in mind—to leave Munich and become a dancer in Berlin (Junge, 17).

Just like the Nazi regime operated, Traudl became Hitler’s secretary “more or less by chance” (Junge, 27). When Traudl passed her dance exams in 1941, she was determined to leave for Berlin, where her younger sister worked as a dancer. During this time, Traudl was also working as a secretary in Munich, and her employer refused to accept her resignation (Junge, 28). Determined to leave that office “at any price,” Traudl accepted Albert Bormann’s—an acquaintance of her sister and Reichsleiter of the NSDAP—offer to work at the Führer’s Chancellery in Berlin (Junge, 28). In November 1942, an opportunity rose for the secretaries of the Chancellery—a typing competition that would determine who would be hired to work for the Führer (Junge, 29-30). Engulfed by the curiosity and enthusiasm that spread amongst the secretaries and office assistants of the Chancellery, Traudl joined the competition. After one thing led to another, Traudl was hired by the Führer himself at the ‘Wolf’s Lair’ in eastern Prussia (Junge, 36).

Traudl was now integrated into Hitler’s inner circle. On a daily basis she dined with her health-conscious employer, socialized with high-ranking officials such as Goebbels and Himmler during late-night tea parties, and accompanied Hitler and his entourage to his Berghof, to Italy where Hitler met with the Duce, and so on. Her main duties as the Führer’s secretary included typing dictations given directly by Hitler, reading and often times responding to Hitler’s personal mail, and her last duty for the Führer was to type his political testament and his will—a demonstration of how well she was integrated into Hitler’s private sphere (Junge, 183). At the climax of her memoir, Traudl describes her last days with the Führer in the bunkers of Berlin, and how she was able to survive the Battle of Berlin, the Russians, and her return to her mother and sister in Munich.

Failing to recognize in time what horrors Hitler has caused, is one reason that explains why the twenty-two-year old, apolitical Traudl Junge chose to work for history’s greatest antisemite (“Blind Spot”). However, a widespread enthusiasm and fascination for Nazism further drove Traudl to the ‘Wolf’s Lair.’ She argues, “In 1942…[I was] eager for adventure [and] was fascinated by Adolf Hitler, thought him an agreeable employer, paternal and friendly” (Junge, 2). Deprived of a father since a very young age, Traudl was immediately attracted towards Hitler’s paternal and protective character (“Blind Spot”). Moreover, growing up in the heart of Nazism, Junge decided to work for Hitler out of an enthusiasm shared by her community—an enthusiasm celebrated in her school and in the streets of Munich where Hitler paraded (Junge, 15). Ellen Frey, a former BdM from Munich and the widow of an SS man, shared her enthusiasm. In Alison Owings’ Frauen, she argues, “Hitler understood how to fascinate women. We did love our Führer, really!” (Owings, 172-73). Erna Tietz, a former BdM like Traudl and a former member of the German army (an antiaircraft gunner), further confirms this sense of enthusiasm by arguing in Owings’ Frauen, “[When Hitler went by in a procession in Königsberg,] I cheered with jubilation” (Owings, 268). Junge argues Hitler was able to fascinate and enthuse his audiences for Nazism by “intoxicating” them and by “manipulating their consciences” (“Blind Spot). In addition to her enthusiasm for Hitler, Traudl’s desire to leave Munich and seek a dancing career in Berlin ultimately tipped the scale in Hitler’s favor. She claims in her memoir, “I would probably never have become Hitler’s secretary at all if I hadn’t wanted to be dancer” (Junge, 27).

The circumstances in Germany during the 1920s and early 30s—a staggering economy and standard of living—helped Hitler gain the support and collaboration of Junge and other women of the Reich. After 1929, Germany’s economy went into a period of hyperinflation—the Germans were exhausted and sought an easy way out (Marcuse, “Germany in the 1920s and 30s,” lecture 31 Jan. 2008). In 1933, Hitler’s advent to power was celebrated as a great event at Traudl’s school, and Traudl—whose family’s standard of living had fallen to a point where her mother was not able to pay for her school supplies—saw this event as a sign of change and economic prosperity to come (Junge, 14). In fact, a few months after Hitler’s rise to power, Max Humps—now divorced from Hildegard—was able to find a job in the NSDAP administration (Junge, 14). Thus, it is a small wonder why Traudl trusted Hitler and did not refuse to collaborate with him. The economic prosperity that accompanied Hitler motivated other women of the Reich to work for him as well. For instance, Erna Tietz argued in Frauen, “[He] promised to help us in a difficult situation, in a crisis situation. And we at the time…trusted [him]” (Owings, 268). Similarly, Ellen Frey claims, “Everybody suddenly got work and bread and therefore people naturally were pro-Hitler” (Owings, 177).

In 2002, in a documentary film titled Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary, Junge argued, “I can’t forgive her,” speaking of the twenty-two year old ‘foolish youth’ she once was, “for failing to recognize in time what horrors that monster caused” (“Blind Spot”). Regardless of the fact that she was neither aware of the atrocities committed against the Jews nor was she an antisemite, her employment to Hitler was enough for Junge to convict herself guilty for partaking in the Holocaust. Readers will notice that Junge was ignorant of the Holocaust because in her memoir and in her interviews for the documentary film she claims she allegedly “worked in a blind spot” (“Blind Spot”). “The word Jew,” claims Junge, “was virtually never used in everyday speech [while I was employed by Hitler]” (“Blind Spot”). She argues, “Details came out later about what really happened in the concentration camps” (“Blind Spot”). Readers will also notice that Junge was not an antisemite because she did not refuse to be friends with Jewish girls, even after the Nuremberg Laws were passed (Junge, 32). Moreover, when Reichsleiter Bormann tried to sabotage the Aryanization process for Hitler’s cook, Marlene von Exner (the Sicherheitsdienst had discovered she had Jewish blood in her maternal line but Hitler, although he dismissed her from her job, asked Bormann to Aryanize her and her family), Junge immediately notified the Führer after she learned of the sabotage (Junge, 117-18).

Junge’s ignorance of the persecution of the Jews was apparently common amongst Hitler’s supporters. “We knew nothing about the concentration camps,” argued Ellen Frey, “that specifically Jews were tortured there” (Owings, 176). Moreover, she claims, “We always said Hitler was just, [and that events such as Kristallnacht were not] directed from above to below, [but were acts committed by the SA]” (Owings, 176). Similar to Traudl Junge, Erna Tietz feels guilty today for collaborating with the perpetrators. She told Owings, “We had not known about it, and if we had known, I believe, some of it would not have happened. And that is a powerful feeling of guilt” (Owings, 277).

Although all three women (Traudl Junge, Ellen Frey and Erna Tietz) argue that they were ignorant of the Führer’s genocide of the Jews, it is important to note that it was not impossible to find out what was really going on in the Reich during war. While reading Junge’s memoir and the interviews of the other two women, at times I felt like they were trying to avoid the truth. Although the evidence mentioned above does confirm Junge was neither an antisemite nor was aware of the atrocities, readers will notice that she more or less chose to be ignorant. For example, she admits in her memoir that “[we] believed what we heard [from the Führer] because we wanted to believe it” (Junge, 83). Thus, she never even tried to defy her Führer and allowed herself to be brought “under [his] spell.” Avoiding the truth in the Third Reich was a common practice. For instance, Liselotte Otting, a woman from Berlin interviewed by Alison Owings, has reportedly claimed, “One was happy not to face such questions. We thought, stay out of it…and thanked God [we’re] not Jews” (Junge, 71).

Traudl Junge insists Until the Final Hour is “neither a retrospective justification nor a self-indictment,” but an “attempt to be reconciled not so much to the world around me as to myself” (Junge, 1). In 2002 Junge shared with her interviewers an incident that took place soon after the war had concluded. She told them, “I was walking past the memorial…to Sophie Scholl and I realized that she was executed the same year I started working for Hitler. At that moment, I really sensed it is no excuse to be young and that it might have been possible to find out what was going on” (“Blind Spot”). Fifty-seven years later, Junge’s sense of guilt was still present with her. However, I believe the publication of her memoir in 2002 and the fact that she took responsibility for her participation in the Third Reich was courageous and unprecedented. Many Nazi members never took responsibly for their direct or indirect participation in the Holocaust—even those who ran the crematoria in the Death Camps or those who refused to house Jews on the run. In 2002, after finally sharing her memoir with the world, Junge was diagnosed with cancer and her fight against it proved to be in vain. In her sickbed, Traudl Junge telephoned the director of the documentary film and finally announced, “I think I’m starting to forgive myself” (“Blind Spot”).

|