Main Text

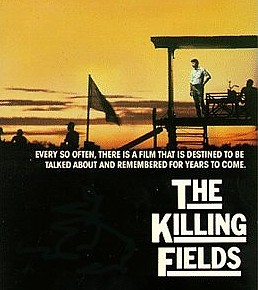

Growing up in the United States, I could not imagine a world where you

could be punished for your intelligence. On April 17, 1975 the fall of

Phnom Penh gave way to the Khmer Rouge, which called itself Democratic

Kampuchea. However, problems in Cambodia began many years before. Pol

Pot assumed power in 1974; and the "Year Zero" began. The opening

of the Killing Fields beings with a voice over of Sydney Schanberg,

describing Cambodia, a paradise, as a victim of war and how this seemingly

"neutral" place became involved in the Vietnam War. (Kuhn, The

Killing Fields) The Killing Fields, an emotionally affecting

portrayal of the relationships between a cast of real-life characters

and the unwavering United States as an ineffective presence in Cambodia.

Amid the ruthless massacre committed by the Khmer Rouge The Killing

Fields puts a human face on both sides of the conflict in Southeast

Asia.

Two excellent films, The Killing Fields and Swimming to Cambodia,

offer insight to the massive genocide that took place under the Khmer

Rouge. Despite the ways in which both films have been cast, they have

been acclaimed for their cinematic and historical value over time. The

Killing Films portrays the lives of three American journalists as

well as a trusted interpreter, Dith Pran and gives an account of the horrifying

fall of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh under the tyranny of the Khmer

Rouge, depicted through the eyes of New York Times reporters and photojournalists,

most notably Sydney Schanberg and his Cambodian protégé

Dith Pran. Swimming to Cambodia essentially tells about Spaulding

Gray’s experiences as an actor in Roland Joffe’s film, The Killing

Fields. The film features Gray in a small but pivotal role as an assistant

to the U.S. Ambassador in Cambodia. Although these films are both depicted

in vastly different ways one is a historical film, while the other is

a dramatic monologue. Both show dramatic insight to the reporters’ understandings

of the term ‘genocide’ and how they used this experience to expose this

information to the rest of the world.

Though The Killing Fields begins

with the point of view of the Schanberg character, the main part of the

film belongs to Dith Pran. In the later half of the film we follow Pran

and his experiences as he "sees his country turned into an insane

parody of a one-party state, ruled by the Khmer Rouge with instant violence

and a savage intolerance for any reminders of the French and American

presence of the colonial era" (Ebert, The Killing Fields).

I think that in this film the most touching points are the scenes that

omit Pran’s personal inner monologues. While, I find these monologues

helpful in gaining insight to the thoughts that might be going through

a prisoner of wars experiences, I find that seeing those experiences had

more impact on me. The Cambodian genocide is highly unknown to many people.

Pran spent four years in the Khmer rouge, and we see how he had to hide

much of who he was. This genocide differed from the Holocaust as we see

that people were killed based off their knowledge. "He [Pran] and

millions of other Cambodians suffered terrible conditions, including long

hard hours of physical labor, hunger, malnutrition, and constant surveillance

under murderous Khmer Rouge" (Kuhn, The Killing Fields). There

is a scene where we see Pran so desperate to live, that he results to

drinking blood from a cow. He is caught and tied to a tree and left to

die. He is only saved when a boy who remembers him from the Airport Road

recognizes him. There Pran gave the boy a Mercedes emblem that was enough

to save his life (Kuhn, "The Killing Fields," scene log).

Cambodians were re-educated, told that this was "Year Zero,"

and that everything they had known before this "pre-Revolution"

had to be erased. In this film there is a specific scene where a child

leads a man to death after she accuses him of not working hard enough

since his hands were not abraded enough. During this commotion, Pran plans

an escape. He hides in the water and waits for the camp to pack up and

leave.

Not too long afterwards, Pran escapes and the following scene shows us

the horrible truth of the "killing fields". Pran discovers the

mass graves of the Cambodians. This scene is especially significant as

it reveals the horror behind the very name of the film. "Under Khmer

Rouge rule, it is estimated that anywhere from one to three million Cambodians

perished. Across the country, there exist many mass graves, or "killing

fields," laden with the bones of thousands of Cambodians who died

during this time" (Kuhn, "The Killing Fields," history). This kind

of a scene shows the audience how much of Cambodia is so undeveloped that

something like these graves could actually happen.

Although Pran successfully escapes, he runs into more problems. Another

Khmer Rouge group captures him, and takes him as a servant. His only chances

of survival were his ability to hide his knowledge of French or English,

which he is indeed asked. However, as the film continues he is caught

listening to an English newscast. "The leader is actually relieved

that Pran speaks English, because he can entrust his son to Pran and admit

that he fears for his life (a mutiny) without any other KR members understanding

him" (Kuhn, "The Killing Fields," scene log). This scene shows us

that no one is safe in this horrific event. Members of the Khmer Rouge

eventually kill the leader. When this occurs Pran, the child of the leader,

and many other men are able to escape, while the Khmer Rouge is busy fighting

the Vietnamese. Although Pran is able to survive, he suffers the loss

of the child as the result of hidden mines. Nowhere is safe anymore. Pran

makes it through the forest to a village where he finds refuge working

with the Red Cross.

The escape of Pran and his eventual survival were not likely during turbulent

times like these. As reviewer Robert Ebert notes, "In a more conventional

film, he would, of course, have really disappeared, and we would have

followed the point of view of the Schanberg character". Yet, the

film is quite a masterpiece at depicting true Asian landscape. Some of

the best moments in the film show us the human sides of desperation, feelings,

trust, loyalty and the inner conversations. However, as I found out in

the end, an actual Cambodian refugee to played the part of Pran. This

casting offers a sincere and convincing depiction of the true emotions

and feelings of someone undergoing these horrific experiences.

While the casting of Pran by an actual

Cambodian refugee is compelling to the story plot, I find that Gray’s

presence in The Killing Fields is very important to complement

his work, Swimming to Cambodia. Swimming to Cambodia is

essentially about the experiences of Gray as an actor in The Killing

Fields. His role in The Killing Fields, though small, gave

him the chance of utilizing his time in Thailand while the filming was

going on. "He seems to have used this time to investigate

not only the fleshpots of Bangkok, but also the untold story of the genocide

that was practiced by the fanatic Khmer Rouge on their Cambodian countrymen"

(Ebert, Swimming to Cambodia).

Interspersed with heavier stuff, gray describes his experiences with descriptions

of marijuana binges, sex shows in the bordellos of Bangkok, as well as

his accounts in great detail of all his findings, from the infamous "banana

show" in a local nightclub to the disappearance of millions of Cambodians

in one of the greatest mass murders in modern history. In his traumatic

detailing of the genocide in Cambodia that took some two million lives

during the Khmer Rouge, Gray punctuates his story with numerous anecdotes

such as encountering a sexually experimental sailor on a train journey,

a description of a journalist's ego, and his own neurotic fear of sharks,

remembered only when he is swimming in an uncharted sea.

This film, perhaps one of the simplest movie sets ever designed situates

Gray in an astonishingly vivid picture of what really happened in Cambodia.

Throughout this 85 minute monologue he sits at a wooden table, furnished

only with a microphone, a glass of water, pointing device, and a small

spiral notebook, as well as the display of two flags hanging behind him

on both sides, one of southeast Asia, the other of Cambodia. The way in

which Gray’s narrative moves along captures an audience's attention as

he motors from one topic to the next, transporting the audience with his

mystical abilities of telekinesis from his apartment in New York to the

idyllic beaches of Phuket, punctuated with comedic punch lines delivered

straight into the eye of the camera. Therefore, when his ‘Perfect Moment’

finally arrives, you are prepared to be right there in the moment with

him.

When they were released, both films

were critically acclaimed. They offer viewers insight to the Cambodian

genocide through two very different views. I think that the coupling of

these two films can greatly enhance the knowledge of people hoping to

seek a better understanding of genocides in the twentieth century. While

these films do not go into depth over the term ‘genocide,’ they expose

it in their own ways. The haunting image of Pran muddling through the

remains of the bodies will haunt anyone who views it. In spite of this

there have been numerous criticisms of Gray’s comical anecdotes pertaining

specifically to his descriptions of some strip shows. He has been criticized

for exploiting the genocide in Cambodia for his own exaggeration. This

can be seen as a serious charge, particularly since most of Gray’s findings

are based on word of mouth. Of course, it can be seen that Swimming

to Cambodia is, on some level, self-exaggeration, but it is worth

making note that in part, The Killing Fields was inspired by the

deaths of millions of the people Gray encountered.

One of the most important distinguishing

factors of this genocide versus the Jewish Holocaust is that the Cambodian

genocide dealt with the mass extermination of millions of people from

the educated classes. Just looking intelligent could have killed you,

or in Pran’s experience, acting as if you are unintelligent could save

your life. Then it is also important to ask the question, aren’t literally

all possible historical subjects exploited whenever they are turned into

fiction? In all fiction movies, no matter whether based on true life or

not, the film directors always has their spin to make the film into a

Hollywood hit. In almost all war movies, for example, the suffering and

deaths of untold victims and turn them into a setting for a fiction story

at the center of a few romanticized characters. Yet, what film is without

criticisms? Despite the criticisms that Gray faced in his films, it brings

to life the fact that every person was involved in this genocide somehow.

These people were not being killed because of their beliefs, but based

on what they know [their background]. I believe it was said best by Pran

inThe Killing Fields: "only the silent survive," namely

that the most deadly factor is within you--your own intelligence.

|