Jews in the German Army

(back to top)

In the story Europa Europa, Shlomo Perel tells an extraordinary

tale of how he survived the Nazi Holocaust. After escaping the German

occupation of Poland by fleeing to the Russian side, he was later captured

by the Germans as they advanced into Russia. Once captured, he pretended

to be German and was recruited as a German soldier. The commander of his

unit liked him so much that he was sent to a prestigious Hitler Youth

program, keeping his identity secret until the end of the war. It is a

tale of survival at the cost of disowning one’s own heritage and of helping

those who ultimately persecute your relatives. My question is, was this

a single case? Did other Jews join the ranks of the army or deny their

heritage in order to survive?  In

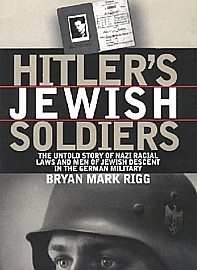

his book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, Bryan Rigg looks at the particular

case of the Mischlinge (the half-Jews and quarter-Jews), and how they

lived and were treated during the Nazi Regime. His book gives new insight

into how this large ethnic population was viewed during the Holocaust,

and how they viewed themselves. In focusing on the Mischlinge who served

in the Nazi army, we come to a realization of how deep personal beliefs

in one's heritage will go, as well as what others will do in order to

survive. In

his book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, Bryan Rigg looks at the particular

case of the Mischlinge (the half-Jews and quarter-Jews), and how they

lived and were treated during the Nazi Regime. His book gives new insight

into how this large ethnic population was viewed during the Holocaust,

and how they viewed themselves. In focusing on the Mischlinge who served

in the Nazi army, we come to a realization of how deep personal beliefs

in one's heritage will go, as well as what others will do in order to

survive.

Many people assume that there were no Jews in the Wehrmacht . Rigg adequately

proves that this is far from the truth. "Although the exact number of

Mischlinge who fought for Germany during World War II cannot be determined,

they probably numbered more than 150,000." (Rigg, Mark. Hitler’s Jewish

Soldiers, University Press of Kansas, 2002) Rigg came to this number

by searching through hundreds of German documents which listed names of

men in the army with ‘half-Jewish’ ancestry, as well as lists of exemptions

for these Mischlinge. If this number is correct, the question arises as

to why these Mischlinge would help to fight for a regime that openly persecuted

them? Rigg tries to answer that question by answering other questions

and issues such as, who is a Jew? Who is a Mischling? Jewish assimilation

in Germany, a history of German and Austrian Jews who served in their

countries’ armed forces, the regulations for Jews and Mischling in the

Wehrmacht, and official exemptions from racial persecution offered by

Hitler himself.

The Nazi regime had sole control in deciding who was Jewish and who was

not when it came to their documentation in identity, as well as who was

a Mischlinge. However, an individuals definition of what it meant to be

Jewish may be different. For instance, Hitler argued that the Jewish father

passed as much Jewsihness to a child as a Jewish mother (Rigg, 16). However,

the Jewish tradition of Hekel states that they inherit their Jewishness

from the mother’s side (Rigg, 7) Mischlinge, was an even more confused

definition, as it implied that one was also half German. It was in determining

which half was more "prominent" that determined one’s identity.

One answer to why some "half-Jews" joined the army may be that some of

the Mischlinge did not think of themselves as Jewish. Rigg summarizes

what one "half-Jewish" survivor, Helmut Kruger, had to say about his ancestry:

He struggled for twelve years to convince the Nazis he was not Jewish

but rather a loyal German Patriot…Kruger insists that he had nothing to

do with his mother’s Jewishness. He was born German and raised as a Christian.

Kruger dislikes being called a Jew, not because he is anti-Semitic, but

because he does not feel Jewish. Kruger believes that he is just Helmut

Kruger, born a German not by choice but by chance to a German-Jewish mother

who, like many Jews, assimilated and shed her Jewishness to integrate

fully into the dominant society. Krguer’s opinion is common among Mischlinge.

(Rigg, 11)

Apparently many Mischlinge did not feel that half of their ancestry should

be reason enough to be considered a Jew over being a German. Moreover,

they were truly passionate Germans. Many like Kruger joined the ranks

of the Wehrmacht in order to prove their "Aryanhood," and be considered

normal. One German Mischling wrote this to his grandmother, "Don’t you

realize how much I’m with my whole being rooted in Germany. My life would

be very sad without my homeland, without the wonderful German art, without

the belief in Germany’s powerful past and the powerful future that awaits

Germany." (Rigg, 28) These Mischlinge thought of themselves as fully German,

they were not trying to hide their ancestry, but mainly trying to show

that they did not believe in it. One "half-Jew," Hans Pollack, learned

of his Jewish ancestry in 1935. Rigg writes:

He had read about Jews in school and the press and felt upset to be associated

with the. ‘I tell you honestly, I don’t like Jews…That’s correct. I would

never do anything to a Jew, I must also tell you that, because the Jew

is also a human being…When I get to know a Jew, he’s no longer a Jew,

but a mensch like you and me. (Rigg, 24)

Hans, like so many others, did not identify himself as being Jewish.

They went to join the ranks of the Wehrmacht to prove their loyalty to

the German people as faithful Germans, not to escape the fate of being

Jewish.

Many Mischlinge, however, followed the same path as Shlomo Peril, that

is, hiding by disowning their religious affiliation.

Field Marshal and State Secretay of Aviation Erhard Alfred Richard Oskar

Milch’s "Aryanization" was the most famous case of a Mischling falsifying

a father. In 1933, Frau Clara Milch went to her son-in-law, Fritz Heinrich

Hermann, police president of Hagen and later SS general, and gave him

an affidavit stating that her deceased uncle, Carl Brauer, rather than

her Jewish husband, Anton Milch, had fathered her six children.… In 1935,

Hitler accepted the mother’s testimony… (Rigg, 29)

This testimony of incest was accepted as a means to save her son’s life,

thus making him pure Aryan and able to serve the Luftwaffe. Ironically,

Brigg later says that there was suspicion that Milch’s mother was also

Jewish, making the Field Marshal and Secretary of Aviation a full blooded

Jew. It is also interesting to note that incest was seen as more socially

acceptable then being a Jew. Through his mother’s own testimony Milch

was able to hide his ancestry, and thus survive the war as a top commander.

Many more Mischlinge soldiers had to hide their ancestry in order to

stay in the army and avoid persecution. Many Aryan mothers would testify

that they had affairs with other Aryan men instead of their Jewish husbands.

Others, like Joachim Lowen, decided to attack their mother’s virtue in

order to hide their blood. "My own brother went to the Gestapo and claimed

that our mother was a slut and had been a prostitute. The Gestapo reviewed

our case and declared us deutschblutig (of German blood)." (Rigg, 31)

These two brothers were then able to hide their ancestry by defaming their

mother and continuing to serve in the army.

Other Mischlinge went to serve in the army not to save or hide themselves,

but rather to save their Jewish relatives. Three Mischlinge brothers joined

the army in order to save their Jewish mother, whom their Aryan father

had divorced her because she was Jewish and he might have lost his business.

"He (Unteroffizier Gunther Scheffler) hoped that as long as one of them

served in the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo would leave their mother alone. Helena

survived the war." Through proving themselves as strong soldiers and valuable

to the German people, these three brothers were able to save their mother.

In the end there are numerous examples of Mischlinge who decided that

the best way for survival was to prove their Aryanhood. The army, for

many, was one successful way to prove their worth to society, and consequently,

to survive.

|

Rigg: Hitler's

Jewish Soldiers

Rigg: Hitler's

Jewish Soldiers  In

his book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, Bryan Rigg looks at the particular

case of the Mischlinge (the half-Jews and quarter-Jews), and how they

lived and were treated during the Nazi Regime. His book gives new insight

into how this large ethnic population was viewed during the Holocaust,

and how they viewed themselves. In focusing on the Mischlinge who served

in the Nazi army, we come to a realization of how deep personal beliefs

in one's heritage will go, as well as what others will do in order to

survive.

In

his book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, Bryan Rigg looks at the particular

case of the Mischlinge (the half-Jews and quarter-Jews), and how they

lived and were treated during the Nazi Regime. His book gives new insight

into how this large ethnic population was viewed during the Holocaust,

and how they viewed themselves. In focusing on the Mischlinge who served

in the Nazi army, we come to a realization of how deep personal beliefs

in one's heritage will go, as well as what others will do in order to

survive.