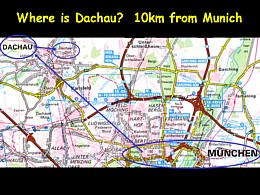

Dachau

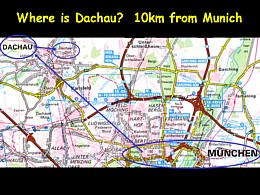

is about 10km northwest of Munich. Dachau

is about 10km northwest of Munich.  The

map of concentration camps in Germany at left shows that Munich and Dachau

are located in southern Germany. (Berlin and Frankfurt also circled.) The

map of concentration camps in Germany at left shows that Munich and Dachau

are located in southern Germany. (Berlin and Frankfurt also circled.)

|

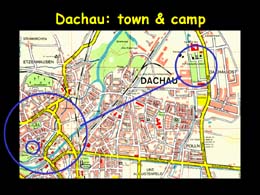

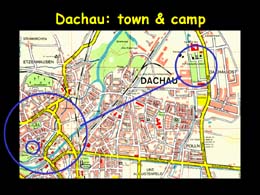

The Dachau memorial site is located about 3km east of the historic city center. The circle within the large circle is the location of the Wittelsbach castle high on the town hill (see top right image on the slide "What was Dachau?", one row down on the right).

Two bus lines, 724 (to Memorial Site Parking Lot) and 726 (to Main Entrance) run from the train station to the memorial site every 20 minutes or so, for a 30 min. trip.

|

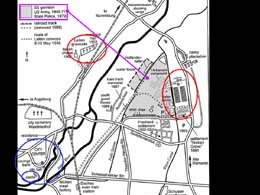

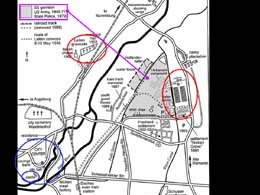

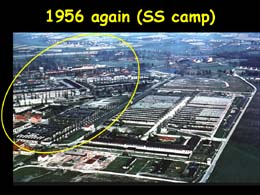

This schematic map from my book Legacies of Dachau shows the relative locations of the historic town center, the Leiten mass grave site, and the concentration camp memorial site. It also show the large area that was a Waffen-SS camp next to the prisoners' camp, with the rail lines dotted in. The Deaths Head SS guards that ran the concentration camp had a relatively small part of their enclosure, near the end of the rail line. |

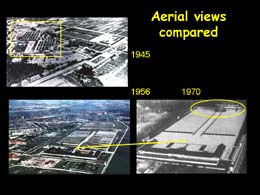

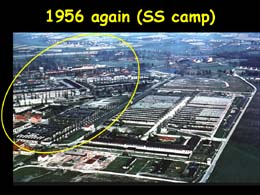

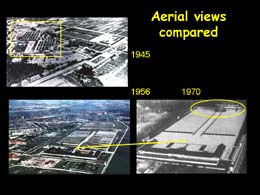

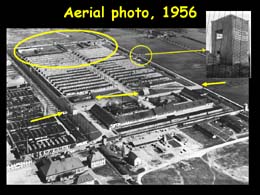

The top image shows the camp at liberation (the SS camp is boxed). The bottom images compare the refugee settlement (1948-1964) to the memorial site (1965-present). The religious memorial buildings at the north end are circled. This is the modern realization of what I call the "clean camp."

|

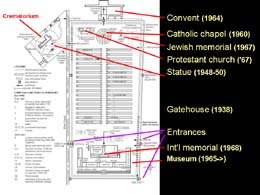

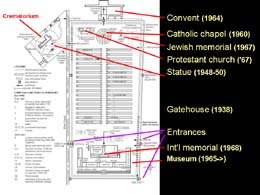

This schematic map of the Dachau concentration camp memorial site is also taken from my Legacies of Dachau. It shows both the camp-era uses of many of the buildings, and the postwar additions.

|

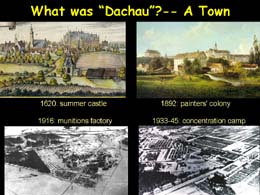

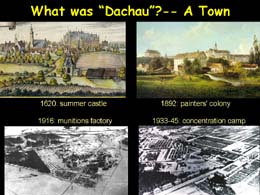

Today most people (except those who live in or near the town) associate "Dachau" with the concentration camp. However, it had previously been known as the summer residence of the Bavarian Wittelsbach kings, then in the 1890s as a center of plein air painting. In World War I a large munitions factory was built there. Its remains were used as the first concentration camp. |

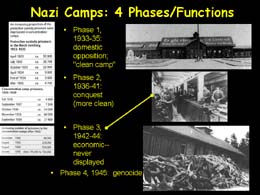

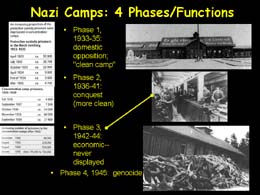

This slide illustrates four of the Nazi-era "Dachaus" that might be remembered and portrayed in the museum: 1+2) the clean camp, 3) a slave-labor factory, and 4) a site of mass murder and death. The tables show how the population of inmates during various periods of the camp's history reflects these functions.

(see the roof in the top image as it appears today, below)

|

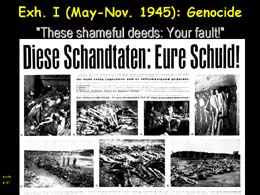

When the camps were liberated beginning in April 1945, general Eisenhower initiated a huge publicity campaign that resulted in what I call the "media blitz." During May 1945 print and film media were dominated by images of the genocidal camps. This image shows a poster that was displayed all over Germany.A similar exhibition was set up within the Dachau camp. I read a description of that exhibition from the diary of a German officer inducted into the US internment camp at Dachau in October 1945. (p. 81)

|

Beginning in November 1945, trials of Nazi criminals were conducted in the former Dachau camp. At that time, surviving former prisoners set up an exhibition in the larger of the two crematorium buildings. The sign at the gatehouse (top) directs traffic there; note that the inscription "Arbeit macht frei" had been removed from the wrought iron gate.

The sign at bottom says that 238,000 inmates were killed in Dachau. Actually, that was the total number that had been registered in the camp. About 40,000 of them died there. |

This exhibition by survivors no longer focused on the genocidal camp, but on the daily brutality the inmates had suffered. Note the whipping rack. Who visited the camp? US soldiers, survivors and their families, foreign tourists (a Frenchman in a beret?).

|

At liberation thousands of corpses were found in the camp and on an unloaded train. To halt a raging epidemic, they needed to be disposed of quickly. About 800 were burned in the crematorium, and 2000-2400 were buried on the nearby Leiten hill, where the SS had already buried about 4000 in fall 1944. 6228 corpses were exhumed in the mid-1950s. Under US army orders, a Munich sculptor designed a huge 35m x 35m memorial to mark the site. It was to be built from the rubble of Munich.

|

The huge memorial was never built. In fact, the gravesite was "forgotten" and fell into neglect. In August 1949 a sand mining operation at the foot of the hill uncovered human bones, sparking an international scandal at the neglect. A new exhibition was commissioned, and a planned accusatory sculpture for the crematorium area was replaced by a more restrained design. |

This new exhibition in the crematorium, also run by camp survivors, but now in the employ of the Bavarian state, was much more restrained and "documentary." It emphasized an overview of camp history, as well as commemoration (see the urn and wreath). Note how the whipping rack was displayed.

|

In April 1953 Bavarian authorities decided to remove the exhibition because it was harmful to the state's reputation. Their attempt to have the crematorium itself torn down was resisted by survivors. As a public relations measure in 1960, they allowed the survivors to install a temporary exhibition again.

|

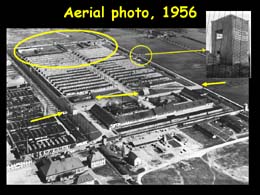

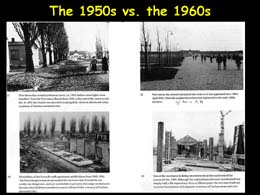

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, more and more relics from the camp were removed, like the guard tower shown here, and the greenhouses, rabbit hutches and brothel at the back of the camp. Two churches, a 1945 Catholic one from the internment camp, and a 1950 Lutheran one from the refugee settlement, were on the roll-call square. |

This color aerial view also shows part of the former SS camp.

|

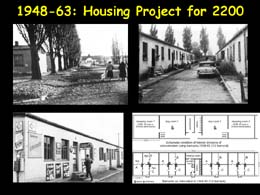

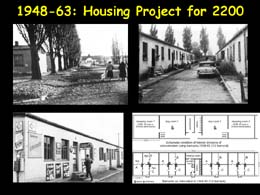

Views of buildings in the refugee settlement, and a blueprint showing how the camp-era prisoner barracks were modified to create 1-, 2- and 3-room apartments.

|

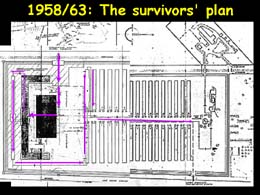

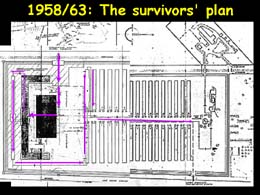

After mobilizing in 1956, the survivors developed a plan to change the refugee settlement into a memorial site. The arrows mark the planned tour route for visitors. |

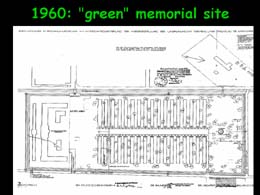

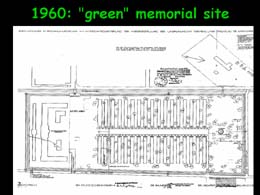

This alternative plan by a Catholic bishop who had been a "special prisoner" in the camp found many supporters in local government. He wanted to plant trees all over the site.

|

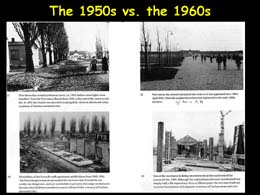

This two-page spread from Legacies of Dachau compares views down the camp street in the 1950s refugee settlement, and the 1980s memorial site (the poplar trees had just been replanted). The modified prisoner barracks were torn down in 1964. Two were rebuilt with reinforced concrete for the memorial site.

|

A central memorial sculpture by Yugoslavian sculptor Nandor Glid, proposed in the late 1950s, was finally dedicated in 1968. An abstract rendition of emaciated corpses strung in a barbed-wire fence, it represents the genocidal camp. Note that the inscription on the administration/museum building roof was not repainted (see slide "Phases/Functions," above.) |

This aerial view from 1970 shows how the memorial site as a whole has come to reflect the "clean" camp. Aspects of the genocidal camp--the fencing, watch towers, and crematoria, have been restored to their original state.

|

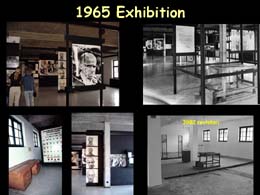

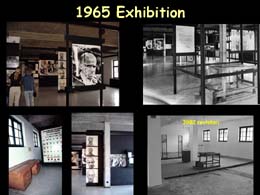

Views of the inside of the museum, as it appeared from 1965 to 2002. The 1965 exhibition was mostly monochrome and had a uniform design relying mainly on photo enlargements. The images at right compare the placment of the whipping rack in in the older and most recent exhibitions.

|

The top two images show the entrance room with brochures for sale in the

boxes at left, and a view into the 1920s pre-history room, with panels

"leaned in" to show that they were put in later. Some excavated

relics are placed under the placards on the wall at lower left (see detail);

the side room at lower right was stripped down to an original layer of

paint--is this "authentic" in some way? (The room never looked

remotely like that prior to 1945.) |

Note the white wall behind the panels in the previous lower-left image

(see detail). During the early

1940s the US army had its mess hall in this room, and that wall was decorated

with murals of a glacier scene (Alaska?), a tropical scene (Hawaii?), and

a view of Manhattan. These murals were removed (destroyed?) during creation

of the museum because they were put in after the Nazi era. No effort has

been made to document with original relics the post-war uses of the camp.

In the 2nd image to the right, for instance, the channels in the floor

were dug when the room was used as a tannery in the 1950s. |

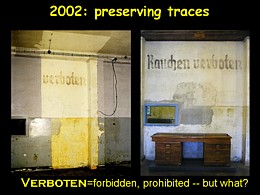

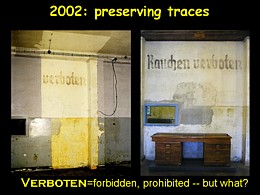

During renovation, when a large cabinet was moved, the word "verboten" became visible and sparked a lot of excitement--what had been prohibited?? After stripping off the other layers of paint, it turns out that new arrivals had been forbidden from smoking.

This raises interesting questions: So normally (some) prisoners were allowed

to smoke? (That doesn't fit with our image of a concentration camp.) Ultimately

the inscription was left visible, but with no explanation. |

The walls in the long transverse wing of the administration/museum building had been changed so often there was even less "original" paint left underneath. Thus they were painted pure white. The hanging vinyl panels and clear glass signage distinguish present-day objects from original camp furnishings.

|

This slide illustrates how remains of the original track leading up to the entrance gate house were discovered in 2005, and after some wrangling preserved as part of the entrance ensemble to the memorial site.

|

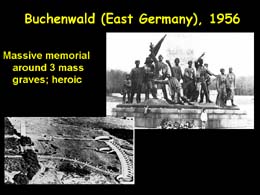

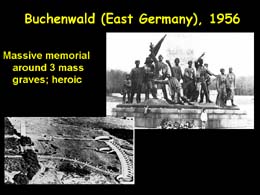

A question after the lecture asked how other camps were memorialized. These two images show how Buchenwald, after 1945 in socialist East Germany, used a heroic portrayal of antifascist resistance and international solidarity as their main theme.

|

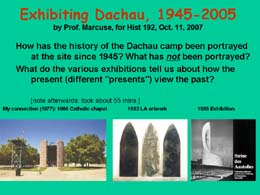

At the end of the lecture I transitioned to talking about my research on how the internet is used by the public to find historical information. The links go to my:

Niemöller Quotation page, and my

2002 talk about History on the Web;

2002

talk about technology in the classroom.

|

intro slide with ques. & personal background

intro slide with ques. & personal background