| Harold Marcuse, review for H-German, (2006), e-mailed to list Dec. 4, 2006; H-Net post

Boris Barth, Dolchstosslegenden und politische Desintegration:

Das Trauma der deutschen Niederlage im Ersten Weltkrieg, 1914-1933.

(Düsseldorf: Droste, 2003). ISBN 3770016157, 625 Seiten, 49,80

EUR.

More a History of Political

Fragmentation than of a Symbol

I agreed to review this book thinking that I would read a detailed reception

history of a potent propaganda "legend" that destabilized the Weimar republic

and mobilized enmity against Jews and Communists. This book is both more

and less. Boris Barth's _Habilitation_ at the University of Konstanz,

a massive tome of 560 densely printed text pages including 3340 well-researched

footnotes, draws on a wide array of primary and secondary sources to recapitulate

and reassess our understanding of the transition from the _Kaiserreich_

to the Weimar Republic. The stab-in-the-back legends (note the plural)

of the title is used as a metaphor for the fragmentation of society into

antagonistic groups blaming each other for the catastrophe of the Great

War. The bulk of the book is devoted to a narrative of the deterioration

of the military situation during the war, and then of the group discourses

that developed from 1918 to 1921. Explicit discussions of various groups'

stab-in-the-back allegations resurface periodically, with the general

historical narrative serving admirably as a background foil against which

readers can assess the veracity of those "legends."

My main criticisms of the book are that it is so difficult to extract

important interpretative points from the densenarrative, and that the

title is somewhat misleading. Aside from the book's primary scope of 1917-1921,

it has little to say about _Dolchstosslegenden_.

| [1] Joachim Petzold, _Die

Dolchstosslegende: Eine Geschichtsfaelschung im Dienste des deutschen

Imperialismus und Militarismus_ (Berlin, 1963); Friedrich Freiherr

Hiller von Gaertringen, "'Dolchstoss'-Diskussion und 'Dolchstosslegende'

im Wandel von vier Jahrzehnten," in: Waldemar Besson and F. Frhr.

Hiller v. Gaertringen (eds.), _Geschichte und Gegenwartsbewusstsein:

Festschrift fuer Hans Rothfels zum 70. Geburtstag_ (Goettingen

1963), 122-160. (to note 4) |

The bulk of Barth's material about that political catchphrase is openly

taken from the secondary literature, adding little of substance to results

already published in Joachim Petzold's 1961 East German dissertation or

Friedrich Freiherr Hiller von Gaertringen's 1963 article.[1] Barth only

summarily mentions the parliamentary subcommittee formed in October 1919

to investigate the reasons for the loss of the war (499-506), and he mentions

only in passing Hindenburg's November 19, 1919 prepared statement to that

subcommittee, which was crucial for the national dissemination of the _Dolchstoss_

image (336f).

However, rather than belaboring what this book does

not do, let me attempt summarize and assess its main interpretative points,

a couple of which are truly innovative.

The first four of nine chapters examine the last two years of the war.

First Barth retraces in detail how a discursive dichotomy developed between

the 'battle front' and the 'homeland' (_Front_ and _Heimat_).

He argues that the latter, which by 1918 was referred to as the "_Heimatfront_",

finally collapsed in the summer of 1918. This terminological dichotomy

enabled army leaders to conceptualize their failure to completely harness

the resources of civilian society to the war effort. Chapters

two through four narrate: 1) the deterioration

of the military situation, 2) how patriotic cultural

trend-setters (the _Bildungsbuergertum_, represented primarily

by the professoriate and the Protestant clergy) rhetorically deluded themselves

about the possibility of defeat, and 3) how the structure

of society adapted to the exigencies of war mobilization by morphing from

an imperial monarchy into a populist parliamentary democracy with monarchist

symbolic trappings. This is all just prelude to what many groups later

conceptualized (or misconceptualized) as stabs-in-the-back.

A brief passage in chapter three is key for those interested in the first

use of the term "_Dolchstoss_" (144-148). Barth discusses three

key sources:

| [2] On the proposed levée

en masse, see Michael Geyer, "Insurrectionary Warfare: The German

Debate about a _Levée en Masse_ in October 1918,"

_Journal of Modern History_ 73(2001), 459-527. |

- Friedrich Meinecke's October-November 1918 writings on the idea of

a levée en masse[2];

- a June 11, 1922 newspaper article, in which Meinecke attempted to

trace the roots of the _Dolchstosslegende_;

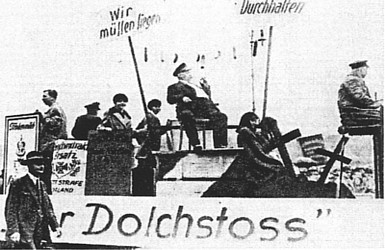

- and a liberal _Volksversammlung_ in the Munich Loewenbraeu-Keller

on November 2, 1918, in which Ernst Mueller-Meiningen, a member of the

Progressives in the Reichstag, used the term to exhort his listeners

to keep fighting:

'As

long as the front holds, we damn well have the duty to hold out in

the homeland. We would have to be ashamed of ourselves in front of

our children and grandchildren if we attacked the battlefront from

the rear and gave it a dagger-stab.'

("_Solange die aeussere Front aushaelt, haben wir die verdammte

Pflicht zum Aushalten in der Heimat. Wir muessten uns vor unseren

Kindern und Kindeskindern schaemen, wenn wir der Front in den Ruecken

fielen und ihr den Dolchstoss versetzten._")

This statement was greeted by sustained, thunderous applause, in contrast

to the speech by Kurt Eisner of the radical socialists, who was booed

and had to leave the beer hall.

In the second half of the book Barth documents how various stab-in-the-back

legends developed independently within different groups and "submilieus"

during and after the November 1918 revolution. Ultimately, he argues,

these legends merged into a unifying symbol for the right wing after 1925.

Chapter five documents the emergence of two "stereotypes"

during the demobilization and transition in November-December 1918. On

the one hand the returning troops were welcomed home with slogans about

being "undefeated in the field"--a notion brought to national prominence

by Friedrich Ebert in his December 10, 1918 speech to the returning troops

at Brandenburg Gate in Berlin (214f):

'Be welcomed wholeheartedly, soldier-comrades, worker-comrades,

citizens [_Kameraden, Genossen, Buerger_]. No enemy overcame

you. Only when the opponent's superiority in people and materiel became

ever more oppressive did we give up the fight. And especially in the

face of your heroism it was [our] duty not to demand senseless additional

sacrifices from you. ... With heads held high you can return.'

Ebert's unknowingly loaded use of "we" and "you" was duly noted in the

newspaper

reports--a crucial fact for which Barth surprisingly relies on the secondary

literature. On top of Ebert's unintentional self-inculpation, some members

of the radical left, most notably Emil Barth of the USPD, claimed hyperbolically

that their long-standing opposition to the war and systematic preparation

of revolution had caused the fall of what we would today call the military-industrial

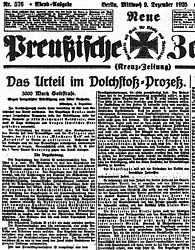

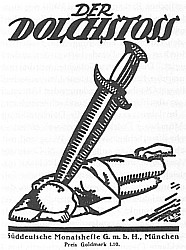

complex. Emil Barth's claim resurfaced prominently in the 1925 Munich

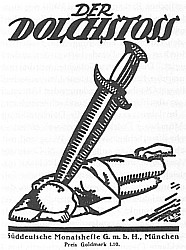

Stab-in-the-Back Trial (223), in which the editor of the bourgeois-nationalist

_Sueddeutsche Monatshefte_ successfully sued an SPD newspaper

editor who had called him a history-falsifier because the _Monatshefte_

blamed the SPD for the loss of the Great War (510-517). In addition to

Emil Barth's proud claim of responsibility for bringing the imperial system

down, another variant of the legend propagated by the far left blamed

the SPD for having betrayed the working class by supporting the war. newspaper

reports--a crucial fact for which Barth surprisingly relies on the secondary

literature. On top of Ebert's unintentional self-inculpation, some members

of the radical left, most notably Emil Barth of the USPD, claimed hyperbolically

that their long-standing opposition to the war and systematic preparation

of revolution had caused the fall of what we would today call the military-industrial

complex. Emil Barth's claim resurfaced prominently in the 1925 Munich

Stab-in-the-Back Trial (223), in which the editor of the bourgeois-nationalist

_Sueddeutsche Monatshefte_ successfully sued an SPD newspaper

editor who had called him a history-falsifier because the _Monatshefte_

blamed the SPD for the loss of the Great War (510-517). In addition to

Emil Barth's proud claim of responsibility for bringing the imperial system

down, another variant of the legend propagated by the far left blamed

the SPD for having betrayed the working class by supporting the war.

The preceding paragraph's information density reflects a characteristic

of Barth's book: It revels in detail to the point of obfuscation. A key

event such as the Munich Stab-in-the-Back Trial is casually mentioned

in chapter five, but not explained until 300 pages later.

Similarly, the book features a huge cast of characters, sprinkled throughout

with abandon, but rarely characterized or reintroduced.

Chapter six convincingly presents several important

new interpretations, which, however, are only tangentially related to

the _Dolchstoss_ concept. Barth's overarching argument is that

various stab-in-the-back legends developed independently in the army officer

corps, among Free Corps in the 1920 Ruhr battles, and among Free Corps

trying to hold the Baltic region for Germany. The officer corps 'had no

mental categories' with which to understand why their troops simply went

home once the demobilization trains crossed the border, so they attributed

this behavior to the corrosive influence of the revolutionary _Heimat_

(231). Then Barth notably reinterprets the Ruhr war following the January

1920 Kapp-Putsch as resistance not by revolutionary workers, but by fed-up

combat veterans against their former military establishment attempting

to return to power (279-283).

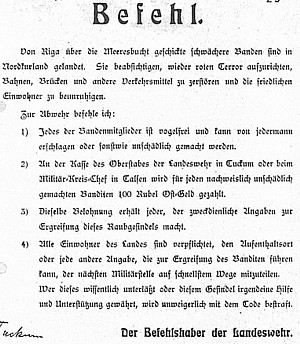

The

striking brutality of the Baltic _Landwehren_, who felt back-stabbed

when the Ebert government cut off their supplies and ordered them to withdraw

under the Versailles terms, prefigured the ferocity with which Jews in

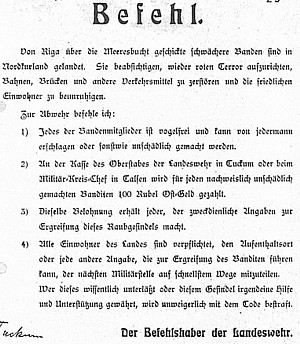

the region were hunted two decades later. An April 1919 order by the _Landwehr_

commander in Riga stated that: any red 'bandit' could be killed by anyone,

a 100 rubel reward would be paid for each killing or for information leading

to capture, and anyone failing to report any information about such 'riff-raff'

would be executed (260, ill. p. 296). Over 3000 men were killed in Riga

in a matter of weeks, with massacres of 500 and 200 documented in other

towns (265f). Once back in the Reich, many of these troops exhibited 'nihilistic'

and politically 'autistic' behavior, in spite of Defense Minister Noske's

generous efforts to reintegrate them. The

striking brutality of the Baltic _Landwehren_, who felt back-stabbed

when the Ebert government cut off their supplies and ordered them to withdraw

under the Versailles terms, prefigured the ferocity with which Jews in

the region were hunted two decades later. An April 1919 order by the _Landwehr_

commander in Riga stated that: any red 'bandit' could be killed by anyone,

a 100 rubel reward would be paid for each killing or for information leading

to capture, and anyone failing to report any information about such 'riff-raff'

would be executed (260, ill. p. 296). Over 3000 men were killed in Riga

in a matter of weeks, with massacres of 500 and 200 documented in other

towns (265f). Once back in the Reich, many of these troops exhibited 'nihilistic'

and politically 'autistic' behavior, in spite of Defense Minister Noske's

generous efforts to reintegrate them.

Chapter seven offers an intellectual history of early

1920s right-wing _Vergangenheitsbewältigung_ (my term) among

conservative monarchists, army generals, Protestant clergy, and voelkisch

and pan-German groups. Barth concludes that the latter two submilieus

'autistically' (one of his favorite adjectives) adopted the justifications

of the former three multipliers. Thus in the stable phase of the Republic

they espoused a nihilism directed against the new social order, without

offering any vision to supplant it.

Chapter eight continues in this vein by looking more

closely at the educated bourgeoisie (primarily professors in various disciplines),

showing how revanchist stab-in-the-back ideas gained traction, especially

among student activists, while liberal voices remained ineffectual. By

the late 1920s, Barth argues, professors who had served at the front came

into conflict with frustrated students who saw themselves as warriors.

Such students bought into the stab-in-the-back rhetoric of the older university

establishment, which had not experienced war, but only dissolution in

the _Heimat_.

Chapter nine, finally, begins to take the narrative

into the later 1920s. It begins with the argument that there were no consensual

symbols to memorialize the war, drawing cursorily on a curious mix of

primary materials from the _Bundesarchiv_ and the already rich

secondary literature on the topic. The next section, on the 'judicial

fights about memory,' covers some of the most crucial events that undergird

Barth's central thesis about how allegations of blame for defeat led to

the political fragmentation of society. However, especially in comparison

to the lavish detail of earlier chapters, the narrative here is tantalizingly

brief, but the interpretations quite explicit. The third section covers

the evolving relationships to stab-in-the-back legends by organizations

such as the _Stahlhelm_, _Reichsbanner_, and _Jungdeutscher

Orden_, as well as in the war literature generally and by various

writers such as Juenger, Remarque, Zweig and Brecht. A separate section

is devoted the Hitler and the Nazis' use of _Dolchstoss_ vocabulary

(such as 'November criminals'), first to justify 'cleaning up' internal

German dissent, then to vilify specific groups such as Bolsheviks and

Jews.[3]

| [3] Indicative of Barth's reliance

on secondary materials about the _Dolchstoss_ itself is his

discussion of _Mein Kampf_. On pp. 543f, notes 343 and 344,

Barth misunderstands Petzold, who actually argues that Siegfried Kaehler's

1946 claims about _Mein Kampf_ are utter distortions. |

Barth did a prodigious amount of primary research in the papers of organizations,

political and intellectual figures, and periodical literature, as well

as in published primary and secondary material. While his inclusion of

even tangential examples in the main text give the book great evidentiary

weight, Barth is not especially successful in drawing out the broader

implications of his research. For instance, although he explicitly disavows

the thesis of a Weimar democracy doomed to failure from the start (4),

seen through this book's lens of inexorably blossoming stab-in-the-back

legends, there is no indication of how the Republic might have withstood

the agitation from both right and left. The book would also have benefited

from a more explicit discussion of the extent to which the stab-in-the-back

myth was a crucial link between Germany's defeat in the Great War and

its pursuit of another European war. Hitler was undoubtedly personally

shaped by the one-two punch of Germany's defeat and revolution, but he

was also driven by positive visions that went well beyond trying to overcome

the trauma of defeat in the Great War.

This point about links between the two world wars leads me to the first

of two unusual lapses in this otherwise exhaustively researched work.

First, in spite of the obvious importance of German war aims for the war

guilt/responsibility discussion, there is nary a mention of Fritz Fischer,

his students, or the debate Fischer's _Griff nach der Weltmacht_

triggered after1961. This omission is especially striking in Barth's discussion

of the War Guilt Department (499ff). I am at a loss to explain it, especially

in light of the fact that the foundational secondary works on the _Dolchstosslegende_

were both published in 1963 during the Fischer debate.[4]

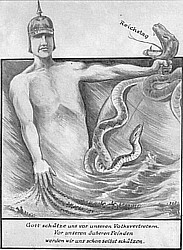

Second, as Patrick Krassnitzer pointed out in his review for H-Soz-u-Kult,

in spite of Barth's emphasis on the symbolic importance of the _Dolchstoss_,

Barth makes no mention of the gendered aspect of its symbolism.[5]

| [6] Gerd Krumeich,

"Die Dolchstoss-Legende," in: Etienne Francois and Hagen Schulze

(eds.), _Deutsche Erinnerungsorte I_ (Munich: C.H. Beck,

2000), 585-599.

[7] Bernd Seiler, "'Dolchstoss' und 'Dolchstosslegende'"

in: _Zeitschrift fuer Deutsche Sprache_ 22(1966), 1-20. |

In sum, this extremely erudite work is of far greater importance to historians

of the 1917-1921 transitional period in German history, than to those

with a more focused interest in the various incarnations of the _Dolchstosslegende_.

Shorter essays, such as Gerd Krumeich's "Die Dolchstoss-Legende" (2000),[6]

offer far more information and interpretative points about the stab-in-the-back

myth, including a discussion of Bernd Seiler's seminal 1966 analysis of

the virtually exclusive use of the epithet "legend" today.[7] In contrast

to "lie" or "fairy tale," both used in the 1920s, "legend" leaves open

the possibility of a kernel of explanatory, albeit undocumentable, truth.

Indeed, after reading this exhaustive study, it is easy to understand

why contemporaries conceived of the widespread fragmentation of their

society since 1917 as a series of back-stabs, even while the historical

record makes clear that the core stab-in-the-back, that between home and

battle fronts, was a bold and utter lie. The question begged by Barth's

thesis is to what extent stab-in-the-back reproaches helped to effect

the disintegration of Weimar society, as he argues, instead of merely

reflecting existing fractures.

Harold Marcuse

University of California,

Santa Barbara

|