| Site

news (back to top) (counter and visitor stats at bottom)

- Sept. 1, 2020: link to Günther anders' papers at the Austrian National Library in Vienna updated; it is now: https://www.onb.ac.at/bibliothek/sammlungen/literatur/bestaende/personen/anders-guenther-1902-1992/237-details

Aug. 8, 2016: available soon, a new translation of Anders' key 1956 essay: Prometheanism: Technology, Digital Culture and Human Obsolescence, translated and introduced by Christopher John Müller (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) ($33 & searchable at amazon; publisher's book page) Aug. 8, 2016: available soon, a new translation of Anders' key 1956 essay: Prometheanism: Technology, Digital Culture and Human Obsolescence, translated and introduced by Christopher John Müller (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) ($33 & searchable at amazon; publisher's book page)

- A translation of the essay ‘On Promethean Shame’ by Günther Anders with a comprehensive introduction and analysis of his work.

- "Günther Anders's prolific philosophy of technology is undergoing a major revival but has never been translated into English. Prometheanism mobilises Anders's pragmatic thought and current trends in critical theory to rethink the constellations of power that are configuring themselves around our increasingly "smart" machines. The book offers a comprehensive introduction to Anders's philosophy of technology with an annotated translation of his visionary essay 'On Promethean Shame', part of The Obsolescence of Human Beings 1 published in 1956.The essay analyses feelings of curtailment, obsolescence and solitude that become manifest whilst we interact with machines. When technological solutions begin to make humans look embarrassingly limited and flawed, new emotional vulnerabilities are exposed. These need to be thought, because our wavering confidence leaves us unprotected in an ever more (un)transparent, connected yet fractured world."

- Konrad Paul Liessmann: "Christopher John Müller's comprehensive and sophisticated presentation and his nuanced translation of Anders' crucial writing “On Promethean Shame” ... demonstrates vividly the significance of Anders as a shrewd and original thinker who was able to anticipate a number of recent societal and technological developments."

- Aug. 8, 2016:

César de Vicente Hernando has just published Günther Anders, fragmentos de mundo (Madrid: La Ovega Roja, 2016), 304 pages, 18 Euro, ISBN: 978-84-937973-4-8 César de Vicente Hernando has just published Günther Anders, fragmentos de mundo (Madrid: La Ovega Roja, 2016), 304 pages, 18 Euro, ISBN: 978-84-937973-4-8

- This is a 'complete introduction to the thought and work of Günther Anders, undoubtedly one of the greatest thinkers and activists of the twentieth century with great relevance for the 21st century, which is still marked by the atomic threat, the dominance of machines and the blurring of reality in the spectacle of the media.'

- Anders' core themes are the 'obsolescence of human beings in a world ruled by machines (television as a producer of reality, image as a matrix of truth, shame before the perfection of devices whose repetition makes them always new, genetic manipulation as a promise of future happiness), and the possibility of the total annihilation of mankind (through the use of atomic bombs, and the technical planning of the murder of thousands of men and women in Nazi death camps).'

- Vicente Hernando attempts 'to place Anders in the intellectual, moral and political conflicts in which his work intervened and allow readers to participate and form their own opinions of his writing and thinking.'

- July 24, 2015: Jordan Levinson has translated Wir Eichmannsöhne into English: "We, Sons of Eichmann: An Open Letter to Klaus Eichmann" (1964). The translation is from the Spanish (not the German original), so some concepts are not as close to the original as they might be. Still, this is a serviceable English version.

- Feb. 2015: New English-language anthology on Anders published:

Günter Bischof, Jason Dawsey, Bernhard Fetz (eds.), The Life and Work of Günther Anders: Émigré, Iconoclast, Philosopher, Man of Letters (Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2014), 202 pp.

($30-47 at amazon)

- Jan. 20, 2015: New Italian publication about Anders: Alessio Cernicchiaro, Günther Anders, La Cassandra della filosofia: Dall’uomo senza mondo al mondo senza uomo (Petit Plaisance, 2014), 400 pages. 25E at Petit Plaisance); with a preface by Giacomo Pezzano, "Anders e noi." Blurb:

Profeta di sventura dell’età atomica e della nostra era dominata dalla tecnica moderna, Anders ha strenuamente messo in guardia i suoi contemporanei dalle catastrofi che da lì a poco sarebbero puntualmente accadute: l’avvento al potere di Hitler, la seconda guerra mondiale, Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Chernobyl. Ogni volta la sua voce è rimasta inascoltata, come quella di una novella Cassandra, perché i suoi moniti sono stati ritenuti inverosimili se non addirittura paranoici. Anders sostiene che ormai, di fronte alla tecnica ed al nostro mondo da essa dominato, noi uomini tutti siamo antiquati, perché antiquate sono le nostre dotazioni psichiche e le nostre categorie filosofiche ed etiche non più al passo coi tempi e totalmente inadatte a comprendere, immaginare ed assumersi la responsabilità di fronte agli effetti smisurati che le nostre azioni, individuali e collettive, oggi hanno grazie ai nostri prodotti ed alle nostre macchine. Come ha scritto giustamente Costanzo Preve: «Ci sono i filosofi tranquillizzanti e i filosofi inquietanti. Solo i filosofi inquietanti servono a qualcosa, e Anders è appunto uno di loro». Affinché allora non si avveri mai anche la sua più terribile profezia, ossia l’estinzione della vita sulla terra e la fine dei tempi, sarebbe bene almeno questa volta prestare ascolto alle sue parole.

- Jan. 5, 2015: The Austrian National Library's page for Anders' papers has a new link [updated again 4/22/2019 and 9/1/2020]; I presume the cataloging is complete, since the funding for it ended on Jan. 1, 2015.

- Nov. 28-29, 2014: Conference "Schreiben für Übermorgen" (Writing for the Day after Tomorrow), sponsored by the Literature Archive of the Austrian National Library, will be held at the IWK in Vienna. (call for papers, due June 15, 2014)

- Sept. 2014: Jason Dawsey completed his dissertation, "The Limits of the Human in the Age of Technological Revolution: Gunther Anders, Post-Marxism, and the Emergence of Technology Critique" (University of Chicago, 2013). He has several publications about Anders:

- "After Hiroshima: Günther Anders and the History of Anti-Nuclear Critique," in: Benjamin Ziemann and Matthew Grant (eds.), Unthinking the Imaginary War: Intellectual Reflections on the Nuclear Age, 1945-1990 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, forthcoming).

- Günter Bischof, Jason Dawsey, and Bernhard Fetz (eds.), The Life and Work of Günther Anders: Émigré, Iconoclast, Philosopher, Man of Letters (Transatlantica Series, Volume 8). Edited by (Innsbruck: Studien Verlag, forthcoming in 2014).

- "Where Hitler's Name is Never Spoken: Günther Anders in 1950s Vienna," in: Contemporary Austrian Studies, Vol. 21: Austrian Lives. Edited by Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser, and Eva Maltschnig (New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press, 2012).

- Sept. 10, 2014: Now available: a complete English translation of Part II of vol. I of Die Antiquiertheit, namely "The world as phantom and as matrix: Philosophical considerations on radio and television" (the link is https://libcom.org/book/export/html/51647).

- Translation from the 2011 Spanish edition by Josep Monter Pérez.

- This prints on over 70 pages as straight text with normal margins.

- Link courtesy of Anders' nephew David Michalis.

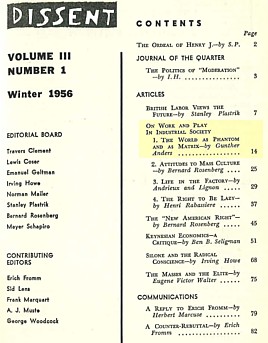

- As noted in a Dec. 2012 announcement on this webpage, there is a 1956 English translation of a shorter excerpt from "The World as Phantom and as Matrix" in Dissent 3:1(Winter 1956), 14-24. (pdf, web)

- Does anyone want to compare these two versions and send me a summary explaining which passages and how the translations compare?

- Apr. 30, 2014: The Internation Guenther Anders Society's website has been launched. For now only in German, but we hope to see an English version soon.

- Apr. 18, 2014: Now updated: Heinz Scheffelweiser's Anders bibliography now includes about 300 new entries, plus an appendix of Italian publications.

- March 2, 2014: Several new publications about Anders were brought to my attention::

- Etica & Politica/Ethics & Politics: Rivista di filosofia/A Review of Philosophy 15:2(2013) has a special section on Anders: "Potere e violenza nel pensiero di Günther Anders / Power and violence in Günther Anders' Thinking"

(TOC)

- Vallori Rasini Guest Editor´s Preface

- Babette Babich Angels, "The Space of Time, and Apocalyptic Blindness: On Günther Anders' Endzeit - Endtime"

- "Christian Dries, "Technischer Totalitarismus: Macht, Herrschaft und Gewalt bei Günther Anders"

- Ubaldo Fadini, "Anders e l'incompleto"

- Edouard Jolly, "Entre légitime défense et état d'urgence. La pensée andersienne de l'agir politique contre la puissance nucléaire"

- Micaela Latini, "La distruzione dell'amore. Esilio e letteratura"

- Francesco Miano, "Günther Anders e la vergogna prometeica"

- Vallori Rasini, "Il potere della violenza. Su alcune riflessioni di Günther Anders"

- Nicola Russo, "Sopravvivenza e libertà: il dilemma impossibile"

- Nov. 2, 2013: Günther Anders ON VIDEO! This 33 minute clip on Vimeo has 3 mins. of Anders introducing his 1987 reading of his story "Die Beweinte Zukunft" ('the Cried-For Future'). It is amazing to see and hear him 20 years after his death (he was 85 at the time of the reading). Many thanks to Stefan Riese for the tip and his kind words about this page.

- July 29, 2013:

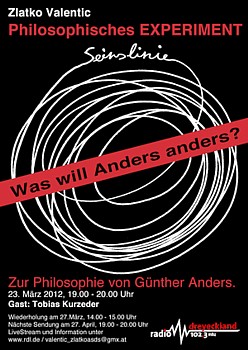

Excellent March 2012, 47 min. German radio program about Anders by Zlatko Valentic: "Zur Philosophie von Günther Anders - Ein Dialog mit Tobias Kurzeder." To listen to the audiostream from Radio Dreyeckland scroll down on that page and click the audioplayer.[link updated 9/20/14] Excellent March 2012, 47 min. German radio program about Anders by Zlatko Valentic: "Zur Philosophie von Günther Anders - Ein Dialog mit Tobias Kurzeder." To listen to the audiostream from Radio Dreyeckland scroll down on that page and click the audioplayer.[link updated 9/20/14]

- July 25, 2013: I've edited the text of my Personal Note, below, and am adding a 36-page pdf of letters that my grandfather, Herbert Marcuse, wrote to Anders over the years 1947-1978.

- Also uploaded: 88 page pdf of entire book Burning Conscience: The Case of

the Hiroshima Pilot Claude Eatherly, told in his Letters to Günther

Anders

(New York/London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1961), 135 pages.

- Another pdf: “Being without Time: On Beckett’s Play Waiting for Godot,” in Samuel Beckett: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Martin Esslin (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1965), 140-151. (8 page pdf)

- May 2013: A graduate student in philosophy at the University of Freiburg in Germany is broadcasting a radio series on Radio Dreyeckland, talking about philosophers for a broad audience.

- The first installment is a dialog with Tobias Kurzeder, who wrote his

- March 14-15, 2013: The annual University of Innsbruck symposium will be held at the University of New Orleans on Mar. 14/15 this year. The title is: "The Life and Work of Günther Anders: Émigré, Iconoclast, Philosopher, Literateur." 16 page pdf program brochure

- Dec. 29, 2012:

Jason Dawsey defended his dissertation "The Limits of the Human in the Age of Technological Revolution: Günther Anders, Post-Marxism, and the Emergence of Technology Critique" at the University of a couple of weeks ago. He noted that shortened versions of three of the chapters of Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen (1956) were published in English in the 1950s/60s: Jason Dawsey defended his dissertation "The Limits of the Human in the Age of Technological Revolution: Günther Anders, Post-Marxism, and the Emergence of Technology Critique" at the University of a couple of weeks ago. He noted that shortened versions of three of the chapters of Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen (1956) were published in English in the 1950s/60s:

- “The World as Phantom and as Matrix.” Dissent 3:1(Winter 1956), 14-24. (pdf, web)

- “Reflections on the H Bomb.” Dissent 3:2(Spring 1956), 146-155. (pdf)

- “Being without Time: On Beckett’s Play Waiting for Godot,” in Samuel Beckett: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Martin Esslin (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1965), 140-151. (8 page pdf)

- Dec. 29, 2012: I've scanned to pdf most of Anders' 1968 book Visit Beautiful Vietnam ABC der Aggressionen heute (Cologne: Pahl Rügenstein, 1968): pdf pp. 1-151, 200-209.

- Feb. 17, 2012: A 2011 French film based on Anders' long-unpublished 1931 novel The Molussian Catacomb was just screened at the Berlin film festival. Titled "anders, Molussien" in German, French and English (thus: "differently, Molussia"), the 81 min. film by young director Nicolas Rey (no relation to other famous Rey filmmakers) is comprised of 9 reels, which are shown in varying order depending on the choice of the projectionist. Berliniale page with director's statement .

- Oct. 21, 2010:

After receiving an inquiry about a quotation from Anders' main work, I found a pdf of Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen: Über die Seele

im Zeitalter der zweiten

industriellen Revolution (vol. 1, 1956; 1961 edition), and re-uploaded it here to make it more easily accessible [removed Apr. 2016 at the request of Beck publishers]. It can also be searched on google books. After receiving an inquiry about a quotation from Anders' main work, I found a pdf of Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen: Über die Seele

im Zeitalter der zweiten

industriellen Revolution (vol. 1, 1956; 1961 edition), and re-uploaded it here to make it more easily accessible [removed Apr. 2016 at the request of Beck publishers]. It can also be searched on google books.

- Vol. 2: Über die Zerstörung des Lebens im Zeitalter der dritten industriellen Revolution (1980; 1992 edition) is also available on google books. The quotation in question:

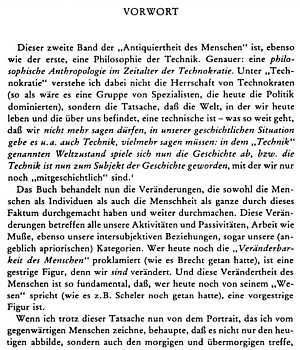

"...the fact, that the world, in which we live and which determines us, is a technological one - which extends so far, that we are not allowed to say, that in our historical situation there is among other things technology, rather do we have to say: within the world's status called "technology" history happens, in other words technology has become the subject of history, in which we are only "co-historical."

is from the Vorwort (preface) of vol. 2, p. 9 (see pdf screenshot).

- Oct. 6, 2010: New anecdote about a visit in Anders' Vienna apartment in 1986 added. It was recorded by German literary critic Fritz Raddatz in his diaries, which were just published.

- Sept. 17, 2010: Since this past July (2010) there has been a GuentherAndersInternational email list (a yahoo group). There are currently 13 members, including Raimund Bahr, Gerhard Oberschlick, and myself.

- Apr. 30, 2010: The Günther Anders Tage 2010, "Zur Aktualität

von Günther

Anders," will be held on 14.-15. May in Marburg, Germany. For the detailed

program, see:

http://www.editionas.net/

- Jan. 10, 2010 (updated 1/16/2011) : The Günther Ander Forum website,

maintained by Raimund Bahr, is moving from http://www.guentheranders.at

to the blog at http://www.guentheranders.com.

You can subscribe to the Society's newletter there.

1/16/2011: both sites appear to have disappeared from the web. Bahr's twitter page doesn't seem to have much to do with Anders.

Bahr's comprehensive biography of Anders is due out this May:

- Raimund Bahr, Günther Anders: Leben und Denken im Wort (Edition Art & Science, 2010), 330 Seiten. (amazon.de page)

Also, on May 14-15 the an Anders symposium will be held in Marburg.

- Aug. 31, 2009: some corrections and links added after corresponding

with Mario Beira, Ph.D. for his study of Hitler and Heidegger. About Anders'

name change: the first publications under the name "Anders" were

in May 1932, according to the 1995 bibliography:

- Plafi, der plastische Film. Nr. 221 vom 13.5.1932, S. 5-6. [Günther

Anders].

Der Star der Polizei. Nr. 233 vom 21.5.1932, 6-7. [Günther Anders].

- The 1935 Amsterdam story "Der Hungermarsch" was published

under "Anders," but his reviews for the Zeitschrift für

Sozialforschung from 1937 to 1939 were published under "Stern."

- A 1948 publication used both names:

On the Pseudo-Concreteness of Heidegger's Philosophy. In: Philosophy

and Phenomenological Research Vol. 3, 1948 (unter: Günther Stern-Anders)

- Sept. 23, 2007: New secondary literature added to

Books and Articles section:

- July 30, 2007: The site Les Amis de Némésis

has published, in French, three texts by Anders, and one about him (direct

links from my Anders

Links page):

- Pathologie de la liberté, Essai sur la non-identification

(1937, by Günther Stern)

- Une interprétation de l'a posteriori (1934,

by Günther Stern)

- Théorie des besoins, suivies d’une discussion

entre Adorno, Anders, Brecht, Eisler, Horkheimer, Marcuse, Reichenbach

(August 1942)

- Jean-Pierre Baudet: Günther Anders, De l'anthropologie

négative à la philosophie de la technique (Part I, Part II

forthcoming)

- April 16, 2006: Anders' papers, previously adminstered

by Gerhard Oberschlick, were given in 2004 to the Austrian National Library

in Vienna, where they are administered by Bernhard Fetz: Bernhard.Fetz@onb.ac.at.

- August 1, 2005: link to detailed French

Wikipedia article by Thierry Simonelli added to links

page. Also created web-formatted archive copy

of Heinz Scheffelmeier's 1995 bibliography.

- July 20, 2005: Another book added to the Books

and Articles section: Berthold Wiesenberger, Enzyklopädie

der apokalyptischen Welt: Kulturphilosophie, Gesellschaftstheorie und Zeitdiagnose

bei Günther Anders und Theodor W. Adorno (Munich: Herbert

Utz, 2003).

- May 2005: Site redesigned and reorganized, links updated,

vanished pages archived from webarchive.org.

New publication added to Books and Articles section:

Thierry Simonelli, Günther Anders:

De la désuétude de l'homme (Paris: Éditions

du Jasmin, 2004), 96pp.

- September 2004: University of Chicago dissertation

prospectus by Jason

Dawsey: "History after Hiroshima: Günther Anders and the Twentieth

Century". This 30-page document outlines Anders' life, with emphasis

on his publications and their influence. It is the best English-language

biography I have seen.

- April 2004: new pages on Anders' third wife, Charlotte

Zelka; with a description of visit

with Anders in 1986; also a link to French edition

of the Antiquiertheit

|